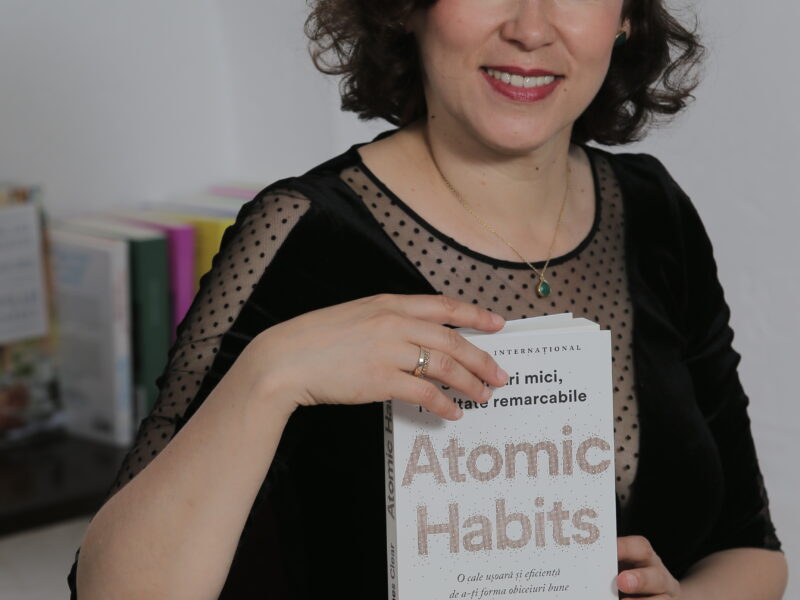

Ioana Văcărescu is editor-in-chief at Corint Junior Publishing House. Until recently, she worked at ALL Editorial Group, where she was a copy editor, and, in the past years, she coordinated Galaxia Copiilor [The Children’s Galaxy], their imprint for children’s books, and she initiated BiblioLOVE collection, dedicated to stories about books. Before she settled among books, Ioana worked at AGERPRES and she was a research assistant at the Romanian Academy Library. Gravitating around words and books. But beyond affiliations and badges, Ioana has been translating and copy editing for about fifteen years. And she does this with so much passion and skill, that the portfolios of many publishing houses contain books she worked on, written by authors such as Norman Mailer, Joan Didion or Sarah Perry.

If a translator, a copy editor and an editor-in-chief walked into a bar, what would they order? And what hour would they set the alarm clock for, the next day, so that they would be able to cross everything off of their to-do lists?

They would have a friendly drink together, I hope. :)

If none of them had an upcoming deadline, they could talk about books (what else?) in peace, while enjoying a beer. Or a coffee, by virtue of their habits. They would set the alarm clock for a pretty late hour, because they also work at night, when they come home, after this small literary circle type of meeting.

What was your first contact with the editorial world like and how/where did you learn this craft from?

The first contact was a social one. I happened to meet a woman from Polirom around 2006, in a context which did not have anything to do with any publishing house: Ioana Filat, an extraordinary copy editor (I would later find out). We talked, she learned that my job from back then also included translations, to an extent – I worked in a press agency, external news – and that I was passionate about literature, she asked me if I wanted to translate for Polirom. Thinking about the next big thing, I took a translation test, everything was OK and I received my first book to translate.

That first book I translated was The Castle in the Forest, the last book written by Norman Mailer. I still wonder how Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu, who was in charge of the Biblioteca Polirom collection back then, let a beginner handle Mailer. I wonder and I am also happy!

Then, there followed other translations for Polirom. Then for Corint, ALL, Nemira, Litera, Trei, Vellant. After a few years, I got a job at ALL, where I found some amazing people (another stroke of luck!), I learned the craft of copy editing and I realized how much I liked it and that it was what I wanted to do forever – books.

So I learned by doing. And I believe it is the best and most efficient way in this industry, somehow. To learn on the job, to learn something from every person you work with and to become better at your job with every book you work on.

You translated and copy edited (mostly) adult fiction, as well as children’s literature. Does the way you work on the books differ from one to the other?

In principle, no. The steps are the same, the work is the same, the care regarding some details is different. When you transplant an adult book into Romanian, of course you are careful to respect the intention, the tone and the purpose of the foreign author. When it comes to a children’s book, you work thinking about the vocabulary of the target-age children, about the words you use – there is no need to use too many expressions they don’t know, but you want to push the limits of their vocabulary a bit, you want them to learn, to ask questions. At the same time, you have to explain the elements of some foreign cultures – without becoming too... didactic –, to think about how much they already know from school, if the curriculum already covered the things the book makes reference to (when it comes to an activity book, a book of exercises etc.). You keep in mind the fact that they will learn a lot from the book you are preparing for them, even if it isn’t a book for school. They will absorb (you hope) information, feelings, experiences – therefore, the book you are working on must be as close to perfection as possible (what can I say, the dream of the flawless book) and as suitable as possible for the children who will read it. After all, books are a sort of filter through which we look at the world – and this filter will shape their thinking.

You have coordinated Galaxia Copiilor, the imprint dedicated to children’s books from ALL Publishing House, where you recently initiated BiblioLOVE, a collection ”about the love for books”. What does the coordination of an imprint/of a collection entail?

It depends on the imprint/collection. :) In principle, it’s about searching for and choosing new titles and series, about sharing them with the team of translators, copy editors and proofreaders (who can be interns, employees of the publishing house, or external collaborators), about taking care of the book throughout its publication stages: a verification of the translation before it goes to copy editing, a verification of the edited version before it goes to pagination, a verification of the paging before it goes to the second copy editing and so on. Then, the cover is prepared, together with the colleagues who take care of the design, the advertising campaign for the series/the book is thought out, together with the colleagues from marketing, PR, online communication and sales.

Coordination, whether it’s about an imprint (a smaller publishing house, coming under the umbrella of an editorial group), or about a collection, entails working with the book, with the text (less than working with the text as a copy editor entails, sadly, because the time is limited), making decisions regarding publishing matters, organizing titles and people.

How did you select the books you published and what are the mechanisms you employed in order for them to reach their target audience?

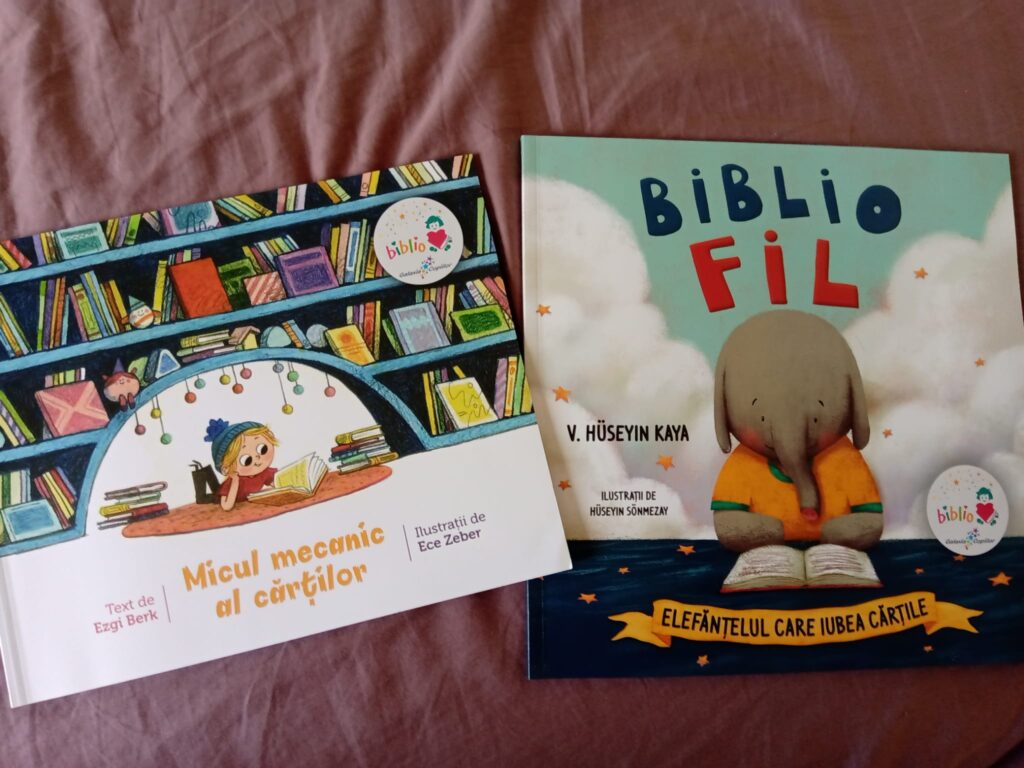

In BiblioLOVE, which has the love for reading at its core, there are only picture books, because the target age is the one of very young readers. So we searched for (and we also found, the world is filled with fantastic books, the publishing houses only need time, money and a working hand to publish them all!) titles which could captivate and educate in the sweetest possible way. :)

We chose them from the catalogues of the foreign publishing houses, rummaging through the drawers of Amazon and Goodreads for books which covered the theme we had in mind, reading articles and charts from various sources – all of them with and about books, reading, words, stories about stories.

We set out with two very charming titles, The Elephant Who Loved Books and The Little Book Mechanic, followed by a whole bunch of interesting things, including a special guest star type of release with Năsuc/Little Nose, the most loved little mouse in Romania!, created by Cristina and Florin Gheorghiu.

Our happiness was huge when we realized that they were very well received by the public – both the parents and the children were excited. Galaxia Copiilor launched all sorts of challenges (all of them online and virtual, because of the pandemic). The answers started to flow in, pictures and videos; we were especially endeared by the videos in which the children carefully read a title, or a page, they retold what they had already learned by heart from the BiblioLOVE stories and they showed their passion for books.

This path towards the target audience is always problematic – the editors hope to reach what they must, how they must. During this period, the steps are, most of the time, online – book launches, workshops, challenges, webinars. Ioana Bâldea-Constantinescu, who has newly become my colleague at Corint, organizes some extraordinary webinars (for children who are older), at the crossroads between book club, literary circle and debate, bearing this exact thing in mind: to bring children closer to books, to make reading and books an ordinary presence in their lives. And I’m not saying this because I’m a nerd (even though I am!), but it honestly is an extremely important thing!

You worked and collaborated with various publishing houses (ALL, Polirom, Vellant, Nemira, Litera, Trei, Corint) both as a translator and as a copy editor. Are there or have there been differences between the type of relationship and the working manner between those two?

I would not say that I felt any huge differences between the working manners. When I act as an external collaborator, the road is simple enough with every book: I receive the proposal for a title (or for multiple titles, and I choose one), I accept it, or I don’t; if I do – I sign the contract, I get to work, I finish my work, I hand in the work. Then, a conversation with those from the publishing house follows, after the book is copy edited/proofread: I receive a Word document with Track Changes, I check it, I tell them if everything is alright – most of the times everything is OK. If I happen to stumble upon God knows what detail of some detail, and because I suffer from a pretty bad case of OCD, I send some type of feedback which sounds similar to this: ”The copy editing is fine, I only have one or two ideas to discuss, buuuuut, I noticed that page X has a missing diacritic, please do not forget to add it during the proofreading phase”. After which... I keep my fingers crossed that those people will keep talking to me. :)

How were those collaborations initiated? Did you go to the publishing houses, or did they come to you?

The first one was, as I said, a happenstance – I met Ioana and from then on, it was smooth sailing with Polirom. I believe, in fact, that this was my biggest luck: I am, in essence, an incredibly lucky bookworm, because I get the joy of making books every day.

After I began the collaboration with Polirom, I was the one who went to the publishing houses, for a while – the traditional method, I would say, I sent the CV, together with a small love letter for literature, I took translation tests, I was accepted and I began to work.

After a while, they started coming to me. Something nice happened with Litera – they contacted me at one point to make me an offer. They wanted to publish a classic, The Razor’s Edge, by W. Somerset Maugham, a novel I translated for Polirom a few years ago. Polirom was not reprinting it anymore, Litera wanted it, the translation rights belonged to me, so they wanted to buy them directly from me and breeze through the translation step. After that, they hired me for a translation, too... for them. Carol, by Patricia Highsmith, it was very popular back then, because the movie with Cate Blanchett had just been released.

In the interview I did together with Adina Rosetti , she emphasized the importance of negotiating the copyright contract for a good writer-editor relationship. The process is similar when it comes to translations and copy editing. What was your experience like, up to this point, how did these negotiations take place? How much leeway is there in the industry now, compared to when you started working?

Sadly, the collaboration contract of an external copy editor is a formality – it has to be signed, so that a basis for payment exists, and so that the person can start working as fast as possible, because they’re waiting for the print. Other than that, the stipulations in it are not taken into consideration all that much, sadly.

Translators are more careful when it comes to their rights, the publishing houses also pay more attention to the rights disposed of by the translator. There, the battle is a matter of time and money – as in any other situation... almost. How many years of exclusive cession? What is the price for a standard page? What happens if the translation is not ready on time, what happens if the publishing house does not pay the translator?

Based on my experience, I can say that the negotiations are not all that harsh. I would say that it all depends on the publishing house and on the experience of the translator, rather than on past vs present – when it comes to the approach. If the publishing house is (remotely) open and it has to do with a good translator, one that they want, and the translator wants to change something in the contract, the modifications are made, or at least, they are discussed. If the publishing house is not willing to offer more (higher payment, more time to work etc.) and the translator is not on the most-wanted list, each of them look for someone else. :)

As translator, I had to ask for a payment raise and I also obtained it. As a coordinating editor, I’ve had a translator ask for a payment raise and I obtained it from the publishing house, because it was about an excellent translator, one I did not want to lose. I also had instances when I could not offer a payment raise, because of the budget.

This is a painful discussion – the low prices. (And, sadly, the payments are sometimes done with great delays.) For both translators and copy editors. It is a work which deserves more attention, recognition, and especially more money. Excellent translators and editors are hard to find. Not even the good or fairly good ones are easy to find. In an ideal world, the publishing houses would offer them financial motivation, they would build loyalty, they would encourage more people who are passionate about books and words to join this field.

Of course, this is also about the decision-making power. About the extent to which the publishing house (through the copy editor) can modify a translation without offending the translator. And this greatly depends on the translator and on the policy of the publishing houses. Sometimes the translators refuse the text they receive, or they express their displeasure with the edited text – rightly so, or... not quite rightly so. There are some excellent translations, joyfully edited by the copy editors, and there are translations which disappoint, because they come to the publishing house signed by translators with high demands, but they are not what they should be.

. It would be great to have a discussion, between translators and copy editors, on the text, with attention and with openness, to discuss each phrase, as one does in a literary circle. This would be the happiest choice of line editing, peace and friendship would (finally) reign between translators and copy editors, and books would have the best possible fate.

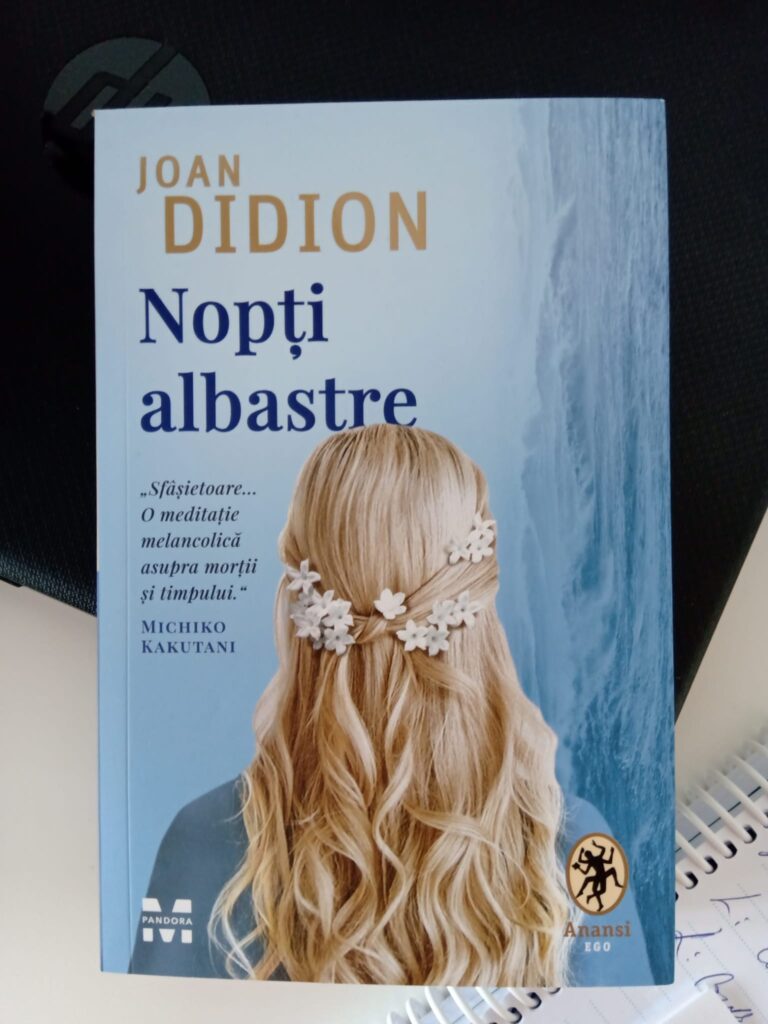

Talking about the experience of translating Joan Didion’s Blue Nights , you said that you let yourself be guided by emotion, trying, at the same time, to precisely and concisely transmit the suffering in the book. Do you have a translation ritual which helps you maintain this balance between empathy and rigor of the text?

Blue Nights was a unique book, rare, because of this huge emotional load. Not all of my translated books were translated like this, very few, in fact, had such a sentimental stake. Translating Didion was a joy (which I also owe to Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu, this time at Trei, in Anansi), but a joy intertwined with pain. There is a lot of suffering in Blue Nights , the type of suffering which shakes you to the core, even if you did not live through it, for the simple reason that you know you will feel it at some point (the one regarding getting old, at least), or because you saw it and you felt it in someone close to you. And Didion, being a journalist (and, needless to say, a remarkable writer), expresses herself with surgical precision, unspeakably simple and concise, and the emotion almost surprises you, it springs from the somber lines, from the restrained writing.

So my only ritual (besides almost endlessly revising the translations) and the most important is asking myself, lingering upon each line: ”Does this sound natural? As natural as the original? Does it sound as though this very thought, this very line, this very book were written directly in Romanian?”. If the answer is ”not yet”, I reread and retranslate.

Referring to the same short interview on the Pandora M. Blog, do all the books you translate go through the same process described there: ”I translated, I edited the translation, I edited the edited version, I modified the revision, and finally, I gave it my best to read the text with new eyes (not empty, though), to critique my translation and to redo it”? How long does the translation of a medium-sized book take, under these circumstances?

Yes, I go through the same steps with all the books I translate. If I were to choose, I would do this over and over again – I would read, edit, re-edit, re-re-reedit until they would be the closest to perfection. Each reading is important, during each reading of the translated text I harshly polish the translation.

Sadly, time is always a problem – both for me, as a freelancer who also has a full time job, and for the publishing houses, who wait for the translations with their ”pen” ready, in order to copy edit them and send them to the printing press as fast as possible.

Actually, time is a great enemy of the book industry, in general, I would say. We are all rushing, herded by deadlines, by budgets (other enemies!), by trends which come and go, sometimes by the readers themselves. It’s great that we want the books to be released fast, what is less than great is that we often find ourselves in situations such as ”Thisʼ will do”. Because it we do, it really won’t. Books don’t turn out as well as they should if the translator is rushing, and, why should we hide behind our words, if they work on the translation carelessly; they don’t turn out well if the copy editor doesn’t have time to sit with the text for as long as they feel the need to; they don’t turn out well if the proofreading step is omitted, and so on.

Translating a medium-sized book... It’s hard to tell, because I work in bouts. It probably takes three to four months, with all the necessary rereads. It depends on the text, on how busy that period is at work. I always wish to have more time to “take care of” the text. Just like how I wish now to retranslate the books I worked on... ten, fifteen years ago, let’s say. I am sure that, with the experience I have now, I would do a much better job. :) And I thank the copy editors who took care of my translations – all of them!

Throughout the period you worked as a copy editor you probably met translators who respected at least some steps of the long process you talked about earlier, and some who breezed through them. How did you fix the latter situations? Do you have a top of some of the most unpleasant such instances?

Of course I had to deal with unsuccessful translations. Many of them, sadly. Sometimes I understood what problems the translators had to deal with and why, other times I could not understand what happened and why I received the text in such a shape (yes, such!), I wouldn’t call it a top, but I have a few books, a few translations I still remember because they were downright outrageous. Situations where I was left with the impression that the translators are not familiar with the subtleties of the Romanian language, or of the source language. I still ask myself how come that they deal with translations, how did they pass (and they did pass!) the step of the translation test.

And, to my great shame, I fixed those situations... editing by retranslating. And that is it. I did not have the time, nor the energy to explain to them step by step, with arguments, line by line, what the problem with the translation was. Of course, I did not hire those translators again. But I was left with the regret that I should have spent a bit of time explaining to them what happened (or asking them what happened!), why it was not fine.

Publishing houses rarely have the necessary time to reject a bad translation when they receive one, and to have it translated again. The copy editor works a lot, retranslates, tinkers with what they can, and that’s it. Sadly.

What are your expectations as a translator from a copy editor? What about when it’s the other way around?

As a translator, I wish the copy editors dedicated the necessary time to each book (it’s hard, I know). I wish there was a leisurely E1, a careful E2, proofreading and re-proofreading.

As an editor, I wish the translators worked with a lot of attention – tone, subtleties of expression, the natural feel of the text.

And, I believe that we would all like to be able to talk more, to discuss the book we are working on together; after all, it is a book we both want to be perfect.

You have translated numerous authors, from Norman Mailer to Sarah Perry, from Somerset W. Maugham to Andrew Nicoll. Which of the translations made you dance with joy [Chandler Bing’s funny dance moment] and which gave you headaches? Do you have a blacklist of the titles from the last category?

Chandler’s dance is still ok, I hope no translation ever (!) makes me dance like Elaine in Seinfeld.

Let’s begin with the ”headaches”. Not at all unpleasant, but more difficult than the usual were the novels set in the Victorian era (The Lie Tree, The Essex Serpent). They are captivating, but some of the details there are terribly dark. At some point I did extensive research on the custom of the members of a family posing for a ”family portrait” with a relative who had just died. They were propped up on a chair, dressed nicely and seated in such a way that made it seem like they were still alive. Gruesome, yes. The Castle in the Forest was a demanding incursion into Hitler’s childhood.

Joy was something I found in many of the books I translated. The Good Mayor, by Andrew Nicoll, is such a sweet love story, and filled with such a fresh and surprising imagination, that I would gladly return to it, at any point in time. The Rosie Project, by Graeme Simsion, made me laugh out loud, it touches upon the subject of Asperger Syndrome with creativity and humor, you cannot read the book without at least smiling a little.

And here I must I must mention a copy editing project - Să nu ne facem de râs în fața furnicilor/Let’s not embarrass ourselves in front of the ants, the novel written by Iv Cel Naiv, which brought me happiness with each line I lingered upon. And the surprise that Iv is more of a novelist than a poet.

What would you recommend to a student or to a young person who is just starting, and who is interested in working in the editorial field? What are the skills they should develop and what tools should they acquire?

No doubt, their critical eye!

Critical eye, attention, patience, a lot of coffee, spell check in Word, a physical copy of the DOOM (dexonline in not quite complete!).

They must like books a lot – for real, not only on a declarative level. :) It is not an easy work, it is not incredibly well paid, at least not in the beginning. So it’s best for them to be certain that this is what they want to do and that they understand what it means to work as an editor, as a translator.

And if they are certain that they want to work in the editorial field, perhaps we can meet at some point. :) At Corint, where I recently moved, together with my OCD, there is a mentorship/apprenticeship program for editors. The coordinators of the imprints from the editorial group each have an apprentice – newly graduated students and book enthusiasts. They will work together, they will show them what they have to do and how, how a book is edited and what happens with the text from the moment it arrives at the publishing house (manuscript or translation) and until it leaves for the printing press.

It is incredibly important – to learn a craft from someone who has already been practicing it for a long time, to work alongside this person and to ”steal”, or even for them to offer you a good chunk of what they know. And I believe that the industry will gain some excellent editors in this way.

It hasn’t been too long since you have become editor-in-chief at Corint Junior. What does the new job entail and what are the short-term plans?

Yes, it hasn’t been that long. :)

On the shortest-term, the plan is to make sure that the imprint’s series continue peacefully, that the books go to print, that the translations and the edited pieces flow following the right rhythm. Making friends with all the existing collections – Smart Age is already my favorite collection, because it targets an age (12+) at which children’s thinking is shaped, when it goes on the long path towards becoming... a grownup’s thinking. It’s the moment when we can model open minds, we can challenge, we can encourage, we can delight. Preparing books bearing these thoughts in mind can be nothing short of joyful.

I also take care of the Adventure and Mysterycollection, where suspense reigns, and I, the Superhero, a collection which offers young readers the superpower of reading and of self-confidence. There are a lot of good books and it’s a wonderful sensation to discover them from the outside, knowing that I will be able to enrich them (these would be the medium- and long-term plans). In this way, I discover them with the enthusiasm of a reader. Well, of a reader with an editorial plan. :)

I snoop around other collections, too, around other imprints. I can barely wait for the release of the book Fourteen Days. An Unauthorized Gathering, a collective novel coordinated by Margaret Atwood – 14 stories written by 14 writers, on a rooftop in Manhattan, during the pandemic. It will be released next spring, simultaneously in English and Romanian, it’s going to be wonderful!

If the Romanian editorial world divided itself into war clans (more or less), who do you think would win, in the end? Who would play the role of the Firestar warrior?

Ooh, you want to break my heart! Firestar, the most courageous and wise tomcat in the history of Warrior CatsI left him at volume 24, but I still think about him. :)

If the Romanian editorial world divided itself into clans... this is going to sound like a cliché, but I hope they would not be enemy clans, I hope they would join forces. Wouldn’t it be great if we all lived in one single clan, with the great and important purpose of releasing books? As many good books as possible, which could reach as many readers as possible.

[Except for the ones in which books appear, the photos belong to Ioana Văcărescu.] [[Translated into English by Irina Adelina Găinușă.]