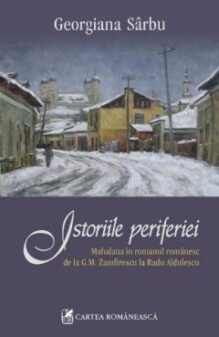

Georgiana Sârbu teaches Romanian language and literature at the National College of Computer Science Tudor Vianu in Bucharest. She published two books, Istoriile periferiilor/The Histories of the Outskirts (her doctoral dissertation, asserted at the Faculty of Letters, the University of Bucharest) and the novel Despărțiri/Breakups, and she participated in the collective volume Povești cu scriitoare și copii/Stories with writers and children and Prof de română. O altfel de antologie de texte/Romanian Language Teacher. Not Your Regular Anthology. She is a character in the poetry of Simona Popescu and, amid the curricula and the compulsory reading lists, she introduces her pupils to writers “in flesh and blood” and to contemporary literature, both Romanian and foreign.

You often post the books you like on Facebook. What are you reading now?

I’m reading a book in the ANANSI collection, from the Trei publishing house, about Istanbul and about the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Like a Sword Wound by Ahmet Altan. I have always been fascinated by exotic cultures and I was even thinking of writing on Facebook about how I discovered Istanbul: for the first time in Elif Shafak’s books and through Orhan Pamuk’s writing; only afterwards did I see Istanbul ”in flesh and blood”, so to say.

How did you begin to read?

To be honest, the first things I read were some fairy tales my mother used to buy when she went to Giurgiu. I spent my childhood in a village situated 20 km North of Giurgiu, and my parents went into town once a month and they came back with all sorts of little books, oriental fairy tales, and so on. I believe I started reading seriously when I was in the sixth grade, when my father stormed into the house and scolded me and my sister for being lazy, for not dusting and for not even knowing who Sadoveanu was. And I remember that he gave me Frații Jedri/The Jderi Brothersto read. With time, the book gripped me and I think I fell in love with a male character back then. But I came to detest Sadoveanu, I don’t know whether because of this novel or because of his life. Sadly, I often make the mistake of associating the author with the man.

What convinced you to go to the Faculty of Letters after attending a high school with an economic profile?

Are you sure you want to hear the story? My parents are both accountants and, even though they are now two farmers working the land, they have studies in the economic field and they dreamt of me going to the Bucharest University of Economic Studies. Therefore, I got into a high school with an economic profile, but I did not like it at all. So in the eleventh grade I pleaded with them to let me transfer to a high school where they had a humanities profile. But they did not agree, saying that I had to become an accountant too. Then, I ”managed” to fail the math baccalaureate. Luckily, I got a 10 in the other exams, but sadly, back then, you did not only have to retake the failed exam; instead, you had to start over with all the subjects. And this is how I got a 10 in the Romanian exam twice, actually three times... Because what you did not manage to prepare for in four years, you could not achieve in one month, and I failed the baccalaureate the second time, too. The third time, I had to do with an even more difficult system, because the minister of education from back then, Mister Marga, though that we should have a more ”ambitious” baccalaureate, not with three written exams, but with five. And this is how, even though I graduated from a high school witch an economic profile, I had to take the Romanian, Math, History, Philosophy and French baccalaureate exams. Then, I got into the Faculty of Letters, and I prepared for the entrance exam on my own, when I was studying for the Romanian baccalaureate, in fact. The literature part I studied on my own; I remember that I was reading Istoria literaturii române/The History of Romanian Literature by George Călinescu: I would place it on my knees and read about all the authors we had to study for the exam. A friend of mine, also from Giurgiu, Raluca Brăescu, helped me with the grammar part; she was the same age as I was, but she had already got into the Faculty of Letters. And so, the odyssey of the economic high school comes to an end.

What was teaching like, in the beginning?

You should rather ask me why I started, because teaching was not my initial dream. I was thinking that I would finish The Faculty of Letters, I would get my Master’s degree, then my PhD, and during all of this, my parents would make it all easy for me and support me financially. Until one day, when my mother gave me a reality check and told me that I had to look for a job once autumn came. Then, I had to attend the tenure exam and I came to teach at Spiru Haret (in Bucharest), which remained very dear to me. I taught there in my first four years. I wanted to work there, but even though I had a tenure grade, it was indeed an 8, it was a substitute teacher position. And only after that I managed to achieve tenure and came to teach at Tudor Vianu. It was a forced start, but I had exceptional classes of children. I will never forget. Let’s say, for instance, that I taught Camil Petrescu and I gave them pointers from literary critique; they went to the library and read. They read Pompiliu Constantinescu, Romanul românesc interbelic/The Romanian Interwar Novel , and they came to tell me excitedly: ”Camil writes about a war of the sexes”, ”the woman represents a danger for the man who is a moral absolute”, ”the woman – a coquettish animal”. It was my favourite class, they read a lot.

How do you manage to fit Romanian contemporary literature among the compulsory themes?

The ninth grade curriculum is very flexible, and us, teachers, have to cover main literary themes. We obviously have to support the act of teaching with a textbook, but as long as I offer them the texts, I am free to do whatever I wish and introduce them to other works. For example, many years ago, we had a textbook from Paralela 45 I was very excited about and we studied Muzici și faze/Music and phases by Ovidiu Verdeș; or three years ago, at Vianu, we studied Groapa/The Dump de Eugen Barbu. Trebuia să asociez și niște autori canonici, de exemplu, la tema familiei, am pornit de la Marin Preda și apoi am legat-o de Eugen Barbu. Adică ți se permite să te joci puțin cu textele. La alte clase este altă poveste, tot ce fac acolo este muncă extrașcolară, ca să pot să-i familiarizez cu literatura contemporană. În primii mei cinci ani la Vianu am ținut un cerc de lectură, unde invitam un scriitor, să spunem Radu Aldulescu, și îi anunțam pe elevi cu două-trei zile înainte, iar ei își cumpărau cartea respectivului scriitor sau doar citeau de pe net. Dar încercam să-i familiarizez cu diverse zone din literatură. Eu făceam asta în plus, pe lângă ore. Dar de ce era mai bine să nu fac la clasă atelierul ăsta? Ca să poată veni toți elevii interesați, nu numai din clasele mele. Făceam un afiș cu evenimentul și în felul ăsta aflau toți. Și eu am învățat foarte multe de la întâlnirile astea. Îți dau un exemplu de când l-am invitat pe Dan Sociu, care ne citea ceva din Pavor Nocturn/Pavor Nocturnus; iar o elevă de-ale mele, Ioana Ciucă, spune la un moment dat „îmi aduce aminte de Cancer Ward by Solzhenitsyn”. And I felt so bad, because I had not read Cancer Ward. You learn a lot from children and from everything you do with them.

When did you first begin to introduce Romanian contemporary writers to your students?

Recently, because I no longer had that much time to organize extra activities, I started to include the authors in my lessons. In the last two, three years, I invited them to my Romanian classes. I invited Florin Chirculescu to join my ninth grade class, he wrote a novel [Greva păcătoșilor] about corruption in the Romanian hospitals, because we had studied Balanța/The Scale by Ion Băieșu and I wanted to show them what hospitals were like in the eighties and what they are like now. And Florin, who is also a medical doctor, came and he drew a ribcage for them on the board. I can link a Romanian contemporary author to what I am currently doing for that class, but the disadvantage is that the classroom is very small and I can no longer invite students from other classes to enjoy the experience. My aim is for all of my students to receive a 10 in the baccalaureate exam. Now, if I manage to bring one or two Romanian authors, it’s wonderful. I remember that I had a class where we studied Iona by Marin Sorescu and I invited Radu Vlad, a former student of mine, who studied literature at Warwick and who wrote a poetry collection [Așa ne-am vorbit mereu] published in a bilingual edition, at Iulia Militaru’s publishing house, Fractalia. I invited him because his themes could be associated with Marin Sorescu’s themes. The problem is that post-war literature is only studied in the twelfth grade, too late, and in the second semester, the students are no longer interested in such things, the baccalaureate is just around the corner! Sadly, we have to cover all of these in a hurry, because the cannon constrains us. The final year of high school begins with Bacovia, Arghezi, Blaga, Barbu; these are the canonical authors you teach for a whole semester. You can obviously teach the avant-garde, but, for the sciences profile, the avant-garde is no longer included in the baccalaureate curriculum, and therefore I no longer insist on it.

What are the students’ first reactions when they meet a writer in flesh and blood?

For them, for the first time, it’s a surprise. Well, I should first say that they were shocked to find out that Nicolae Manolescu is not dead, they thought that he had died sometime in the nineteen-hundreds. Some are excited to ask questions, to unravel them, others are not as fascinated. What I can say is that when I invited writers for our book club, the students’ interest spiked; I mean that the interaction between them had to be stopped by me, because otherwise I could not manage to do everything I had set out to do. But when you bring them in class, they are not all extremely interested, because many have had their life paths already chosen, by them, or for them, by their parents, sadly, and they are not all interested in reading. Luckily, at Vianu, the children do read.

Which of the contemporary writers you invited was the most popular among students?

I have to say that the poets were more popular among them and I believe that the meeting with Stoian George Bogdan was very successful. But also the one with Dan Sociu. I invited them twice, in different years. They also liked Teodor Dună very much.

Do the students remain interested in reading, or in Romanian contemporary literature after the meetings with the writers?

Yes, they keep reading and discovering their favourites. It’s true that I pushed them a little in this area, too. For instance, this year, with the ninth graders, we covered a pretty sensitive theme: Romania between the Orient and the western world, when we studied Istoria unui galben/The History of a Yellow. And there is a chapter about the history of the Roma people, so we watched Aferim! in class and I assigned them to write an essay about mentalities in the Romanian territory, with the mention that they had to link the mentalities from back then, whether those seen in the movie or those in Istoria unui galben/The History of a Yellow, to the mentalities from contemporary literature. Of course, I also offered them a reading list, and they read Radu Aldulescu, Ion Băieșu. They chose various examples, and I did not have to force them to do so.

Many students continue their studies abroad. How much does this exposure to Romanian literature matter along the way?

Not only to Romanian literature, because I ask them not to limit themselves to Romanian literature. For example, there was a time during which, if I was fascinated by the Orient and the uprooted, I told them to read Middlesex. And there, in their studies, any reference, explanation, or contextualization helps them a lot, because the professors are fascinated by phrases such as ”man is a social animal”. And even the students who talk about this are considered exotic by their other peers.

What are the best tactics to encourage students to read?

The reward-system works best. For example, for the essay I talked about earlier, I told them that those who supported their arguments with the most examples from contemporary literature had the best chances to receive a 10.

What about for your own children?

I use the reward-system with them too: ”You’ll get your phone back if you read.”

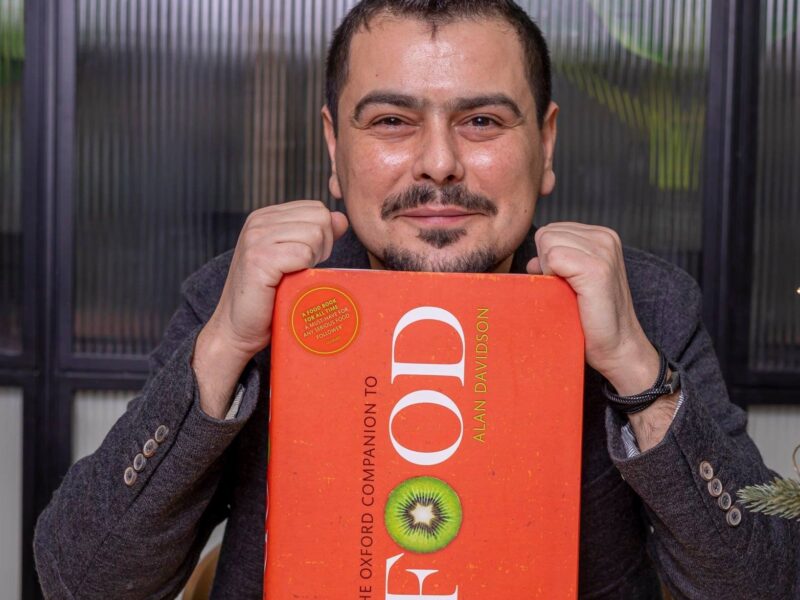

Besides the guests who visit them, during the Romanian classes, the students have a writer in front of them. You published literary critique and a novel and you participated in two anthologies. How did those books come to life?

If we talk about Despărțiri/Breakups, I believe that I wrote the first drafts sometime in high school. I used to commute to Giurgiu for tutoring and that bumpy road, and a bus with falling metal sheets, which was so rusty that you could see the pavement beneath your feet, inspired me. I believe that was the kernel of the story. Later, there were certain filtered experiences. I believe I finished writing it after I gave birth to Stela. I wrote a part when someone very dear to me died, I wrote another part after another terrifying experience, and I rushed to publish it, in order to get rid of it, because it was always on my mind. Rereading it now, years later, I see that it has its weak points, it is as though I wasn’t the one who wrote it, if I think about it.

What was the relation with the publishing houses like, how did you come to collaborate with Cartea Românească, and the with Casa de Pariuri Literare?

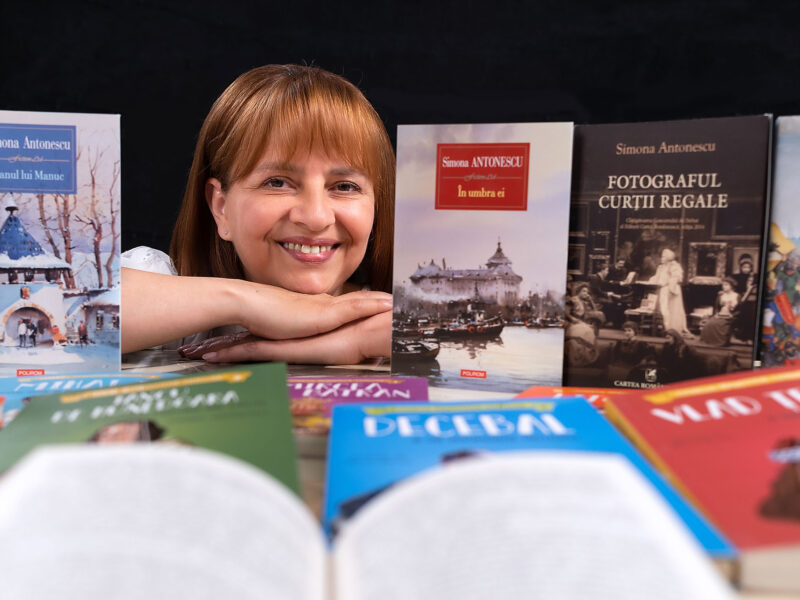

My PhD thesis, Istoriile periferiei/The Histories of the Outskirts, was published thanks to Radu Aldulescu, who was there when I defended my thesis. I did not even know him. But I believe that he read a copy of the thesis and told Miss Mădălina Ghiu that someone wrote about him. And I sent the manuscript to Miss Ghiu, at Casa Românească, and she liked it. I did not modify anything in it, it was more colloquial in nature, including the subject. But I remember how proud I was when Ovidiu Șimonca called me to tell me that Paul Cernat wrote about me. The first review was written by Paul Cernat and I will never forget that it had three columns which seemed laudatory to me, and in the fourth one, he tore me apart. It seemed to me like the most constructive literary critique and that thrilled me, I had never even hoped that such a thing would happen to me.

At Casa de Pariuri Literare I know Cristi [Cosma], because I invited many of the writers published there to speak at the high school, such as Livia Ștefan, or Veronica D. Niculescu. I told him that I also wrote a novel, and he wanted to see it and then he published it.

What is the posterity of the books? Are they being reprinted? Do you still receive echoes?

Cristi suggested that I should reprint the PhD thesis at his publishing house, and Despărțiri/Breakups, too, but I believe there is some rewriting to do. Just like with my latest novel, still unpublished; I did not manage to write the last chapter, because I put my literary life on hold, in order to take care of my children. And I no longer have time to write.

Did you talk to your students about your books?

The PhD dissertation helps them when it comes to the mentalities project, I assign them to read the chapter about language, and the one about metropolitans. When I published Despărțiri/Breakups, many years ago, they came to the book launch and I was very excited. But I generally don’t tell them that I’m a writer, because there is no point in bragging with something that happened many years ago.

If you were to meet with Nora, from your novel, now, which book from the most recent ones would you recommend to her?

I would not recommend any book to her, I would tell her to seriously start studying computer science, math, to study artificial intelligence and to leave the country. After I failed to adapt in Germany, which obviously happened due to age and due to the inability to adapt to something after the age of forty, this is what I would advise young people to do, to tailor a path for themselves adapted to their current conditions.

(Interview recorded audio and transcribed by Cosmina Mavrodin.) (Translated into English by Irina-Adelina Găinușă.)

The photos are part of Georgiana Sârbu's archive.