Lucian Vasile is a historian; he studies contemporary history, and also the history of his hometown, Ploiești. In 2009 he launched RepublicaPloiesti.net, in 2013 he set up The Organization for Education and Urban Development (AEDU), and a year later he self-published his first book,The Sacrificed City. The Second World War in Ploiești. Under the AEDU umbrella, he released other eleven titles he either wrote, edited or published. In 2022, after having coordinated and contributed to some collective works of historical studies, released by various publishing houses, he eventually published The War of Spies. The Secret Actions of the Romanian Exile in the Early Years of Communismat Corint Publishing House. The book is based on his PhD thesis he defended at the "Nicolae Iorga" Institute of History of the Romanian Academy. Lucian finds pleasure in reading, and also in researching archives, writing, publishing and organizing historical tours. He sometimes competes for the “Who gets to pet the most cats” award (a competition he rarely wins). He enjoys reading every evening, in heavy rotation, books about Gruffalo and his daughter, about the monster who brushes his teeth and about George the Curious.

Pubs, Bullets and Palaces is one of the most beautiful titles you’ve ever come up with; it’s a collection of short texts you edited some time ago. If you had to define your professional journey in three words, what would those words be?

I would say that the three defining words are Almaș, passion and Communism. I think everything started when I was little; it was around the time I was able to read fairly well when I stumbled upon a book of historical short stories written by Dumitru Almaș. I wasn’t old enough to understand the ideological undertone of the text, but that was the moment I fell in love with history. The second important moment was when I did the mistake of turning my hobby into a career, so, despite having studied Mathematics and Informatics in college, I decided to take a Bachelor in History. The last element of the aforementioned trilogy is the fortune of working in the field of contemporary history, which enhanced my chances of meeting valuable people and of undertaking research on the topics I am interested in, such as the history of Communist Romania and the history of Ploiești).

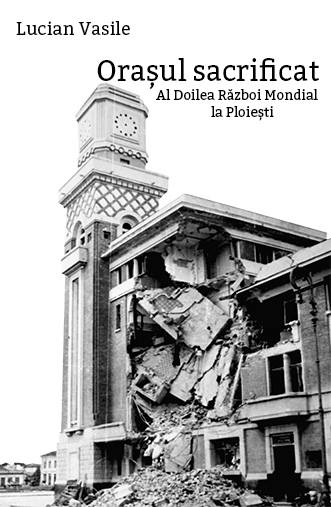

In 2014 you self-published The Sacrificed City. The Second World War in Ploiești. Why did you choose to release the book by yourself?

At the beginning of 2013 I set up The Organization for Education and Urban Development, an NGO through which I intended to develop various projects on the local history and other related topics; I had been working for these projects for around four years then. My intention was that through AEDU I would undertake research, organise walking tours and exhibitions, hold various workshops, alongside other events and, last but not least, publish books. Nevertheless, back then I didn’t know what publishing a book would entail; I was under the impression that having my own publishing house would be a walk in the park. When I started pondering the idea of starting one of my own, I realized that it was rather complicated, especially because my resources were limited. I was expected to have an editorial plan, along with a list of titles I would have commited myself to publish, and the whole idea seemed too complex and out of reach. I wouldn’t have been able to know the impact of the very first published book; how would I have been able to anticipate the number of prospective titles and the publishing rhythm? Let aside that I should have started a LTD, which would have brought different accounting responsibilities, along with the minutiae of the paperwork that comes with it – which I wasn’t able to fully understand. I didn’t want to unnecessarily complicate myself, so I thought of a more useful way of investing my time and resources: I decided to keep the project at a small scale and rather self-publish my book. In these circumstances, my book wouldn’t benefit from a CIP description [Cataloguing in Publication] but I didn’t find this aspect crucial to my work; I believed that releasing a good, attractive and easy to read book is more important. Furthermore, I was in charge of the entire publishing process, from editing the manuscript to the distribution and promotion stages. Despite the challenges, I didn’t step back, not even in the moments when I didn’t know how to do certain things, which I eventually figured out as I went along.

Self-publishing involves juggling the stages of a book publication, from editing the manuscript to promotion. By taking your first book as an example, how did you organise all these stages? Let’s start with the editing aspect and DTP.

The first print run of the first book wasn’t as I thought it would be – in fact it was far from how I had initially envisioned it. However, in hindsight, it was a useful kick in the teeth. By publishing this book I learnt that if you want your work to be good, you must pay great attention to quality and treat the project seriously. I admit this might come across like a truism or an editorial demagogy, but I strongly believe this is a must for a good editor. First of all, the copy editing part has to be done by someone who has a good command of the Romanian language and who pays great attention to every line, every detail. Furthermore, the copy editor must be clear headed and focused; otherwise even the greatest copy editors can miss an “Hes gone.” Then the copy editing must be done the old school way: making amendments using the pen on the printed copy version of the manuscript. No, it doesn’t work on a computer, regardless of the type of screen. If they do that on their computer it’s very likely that they’ll miss some errors, irrespective of how attentive the copy-editor is. Then the editing norms need to be set from the very beginning: what are they going to use to mark their notes: ed. or Ed.? How are they going to mark the titles, by simply italicize them or by using inverted commas? If these aspects are not established from the start, the text might lack unity. The indications and annotations need to be very clear, so the person editing the digital format will understand what to do. After this first phase of editing, the second one comes (the so-called “clear-headed one”), followed by a very important stage: proofreading, which is not optional, but essential and of utmost importance. It is preferable that the proofreader does not coincide with the copt editor; it should be someone who hasn’t previously seen the text and they need to read it very carefully, pay attention to every letter, every comma and every apostrophe. Ideally, the text is returned to the copy editor for final corrections, on paper once again, and then the text should be good to go to printing.

Regarding the DTP phase, as far as I’m concerned this is the most rewardingpart. This is because you can see the progression of a word document to the final form of the book. These stages unfold under your own eyes. Nevertheless, the desktop publishing phase brings various challenges: you need to be careful with the pages’ margins so the book is bound properly and the reader doesn’t need to pull the pages in order to read the beginning or the ending of the line. You need to find all sorts of tricks to fill in the gaps between the text itself and the footnotes and, last but not least, you should be able to guarantee a balanced text, so that the content isn’t crammed, but, at the same time, not to have a too thick book for the sake of making it look bigger. Regarding DTP, in a lack of a specialized software, you can easily work it in a Word document, whereas albums and other projects containing a large number of images are more suitable for being edited with a software like Adobe Indesign.

The cover of the book deserves an entirely separate discussion. In fact, in my opinion, the cover is as important as what you can find in the book itself. Well, in general terms, there are three important elements that influence the overall success of a book: the cover, the title and the topic. However, in terms of DTP, the cover can either guarantee the success of a book or let it dust on the bookstores’ shelves. The cover needs to stand out from the crowd, be it among other titles from the bookshop, or among the search results when going through the recommendations of online retailers. The cover needs to be expressive, vivid, preferably colourful, clear – I was surprised to see that in 2022 some books still have pixelated cover photos, even in the case of prestigious publishing houses – and non-ridiculous. I know the last criterion might come across as subjective, but I don’t think a cover with both Ceaușescu and Antonescu is attractive. Sometimes way too many visual elements are crammed together: soldiers, planes, flames, a picture of Hitler or other historical figures. Having a few more spare covers is always the safe way to go. There were some cases when I wouldn’t have thought that particular photo would go well with the book, but when I added the title on top of the cover and I saw how they came together, I was nicely surprised.

A book needs an ISBN code allocated in order to be added to the National Library database and to be identified internationally. How do you get this code when it comes to self-published books?

There’s a form on the National Library’s website which needs to be filled in and sent. Up until two-three years ago it was enough to send the form along with the cover of the book, but they recently changed it and now you’re required to send the content of the book in a pdf document. I can’t tell you why because I don’t know. The limit is set at two ISBN codes a year per person. Anyway, if you want more than two it’s very likely that you need your own publishing house.

Can you tell us a little bit about your adventures with the printing houses; also, how do you know when you have the perfect match?

I’m still looking for that printing house really. Printing houses are like people: they’re sometimes in a good mood, there are also moments when it’s difficult to communicate with them, there’re even occasions when they don’t reply at all and so forth. I find it surprising how big the differences are between the offers I get from printing houses. Obviously, the price they request is an important criterion when it comes to choosing the one you’d like to collaborate with, but there are other aspects to take into consideration as well. We’ve always tried to build a relationship of mutual trust with the printing houses. The reason lies in my intention of keeping a sense of unity among the books of the same series. However, unfortunately it’s not always possible to have a long-term relationship with the same printing house; therefore I went through other collaborations as well, and I learnt something from each.

It’s important to know what the print run should to be, because it defines what you have to look for: digital printing houses, for print runs up to 500 copies, or offset for anything exceeding this number. The digital method offers you the advantage of printing a limited number of books, but it is often more difficult to find a competitive price. However, printing the book digitally creates some confusion: some books will have up to eleven editions, even though they’re only print run extensions, they’re not new editions per se. Pretending to release a new edition with every print run gives the false impression that the book is successful. It’s not that difficult to pretend to have reached the 10th so-called edition if the print runs have no more than a dozens of copies – which is way less than a single offset batch of 1000 copies. The offset method can be more affordable, however you need to prepare yourself for this printing method. At some point I went for the offset method at the same printing house, and when the first half was delivered I struggled for storage space. Therefore, the offset becomes suitable either when one thinks they can sell a large volume of books quickly, or, in the case of small yet steady sales, when one has access to a small storage facility (that optimally, does not cost a fortune).

Furthermore, it’s also important to know what your book should look like: what type of paper you’d like them to use: 70 grams per square metre or 80 g/m2? What type of paper you’d like for the cover: the thin version of 250g/m2, the thick one of 300 g/m2 or hardcover? How would you like to bind the book: gluing the pages or sewing them together? It’s also very important to find a printing house that knows how to communicate efficiently; at some point I had a problem with the spine of the book because they didn’t say clearly how thick the book would be, so I could work the cover in Indesign. For this reason I find it very useful to be informed about the thickness of the page. This helps me figure the thickness of the spine as well, so I can avoid this backwards and forwards game “the cover is good / it’s not good.” Last but not least you must take into consideration the context within which you’d like to release the book. One can expect that during the weeks before Gaudeamus or Bookfest book fairs the printing houses would prioritize the big publishing houses, so it wouldn’t be advised to publish then because there’s the risk that the delivery dates might be pushed back. The same rationale applies during the political campaigns when the printing houses are overwhelmed by the political parties which blow up their budget on flyers, brochures and newspapers. Obviously it is more expensive to print a book then, so, in essence, you need to anticipate the right times for releasing your work. Sometimes unexpected events can intervene, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which blows everything up, doubling the printing cost (in the fortunate case when printing houses are not out of paper.)

Amongst the challenges of self-publishing a book is the distribution. How did you identify and establish relationships with the distribution and sales channels for the AEDU books?

The first way of doing it was to contact the distributors myself. I didn’t expect them to contact me first (I’ve seen some cases of this kind, and then the editors were surprised that sales didn’t go well). I did my best in identifying any possible ways of getting my books out there and making them appear in the search results. A large number of AEDU books are dedicated to the people from Ploiești, so getting in contact with the bookshops from Ploiești was a sensible approach (thanks to Andi Enache, the manager of Cărturești Ploiești, who was open and supportive). When it comes to other channels, especially online retailers, I was lucky to already know people working in the acquisitions sector.

The last and arguably the most important aspect of self-publishing a book includes the promotion strategies, which ultimately lies with the author. How do you get to promote your books?

As far as I am concerned the authors themselves should be responsible for promoting their own books. If they’re not willing to do it, why would someone else want to do it for them? Furthermore, they know better the message they’d like to get across with their books, their target audience and what they’d like to achieve through promoting their books. First of all, they should work with good social media specialists, which are not easy to find because there are a lot of so-called communication and promotion specialists, PR specialists and other professionals. Simply posting on Facebook and Instagram isn’t enough as you only get a few likes and a low audience reach. You need to know when to post, what the key-words are, how to create and incorporate the visual elements (again, ideally there should be someone who understands graphic design, or at least someone who knows how to work in Canva) and where to post. I did all these, so I got to learn how to create a poster, a promo, a press release. An important lesson is that promotion takes time. A lot of time actually. The effort needs to be consistent. There’s no point in having a successful post this week if you don’t plan to make another one the week after. You end up losing the momentum you’ve just gained. I think promoting a book is the underdogof the book publishing market here in Romania, I find it underappreciated. An author simply cannot secure good sales if people don’t know about their book; it has to be recommended to them or at least to have people around talking about it.

I paid particular attention to book launches, mainly due to my aversion towards conventional events. With every book I launched I tried to avoid turning it into an old-fashioned event where a group of people sit at a table, talking to other people sitting on chairs, similar to being at school. I tried to achieve innovative and creative events and retain an element of entertainment. For example when I released the albums on Ploiești during the First and the Second World War, I invited my friends from Deutsche Freikorps, a NGO doing military cosplay. They were dressed in period uniforms and held some interactive presentations. For the launch of an anthology I edited and distributed a newspaper in which I mixed old news with interviews and some information about the authors included in the book. I envisioned it as an imagination exercise: how would have been for an interwar journalist to have taken part in modern-day events like this? For another book I launched, one whose cover had a gentleman wearing a topper hat and a suit, I invited my brother dressed alike, so the participants could take photos with the “Gentleman with the topper hat".

What were the most difficult challenges you faced on your editorial journey? What about the most fulfilling moments?

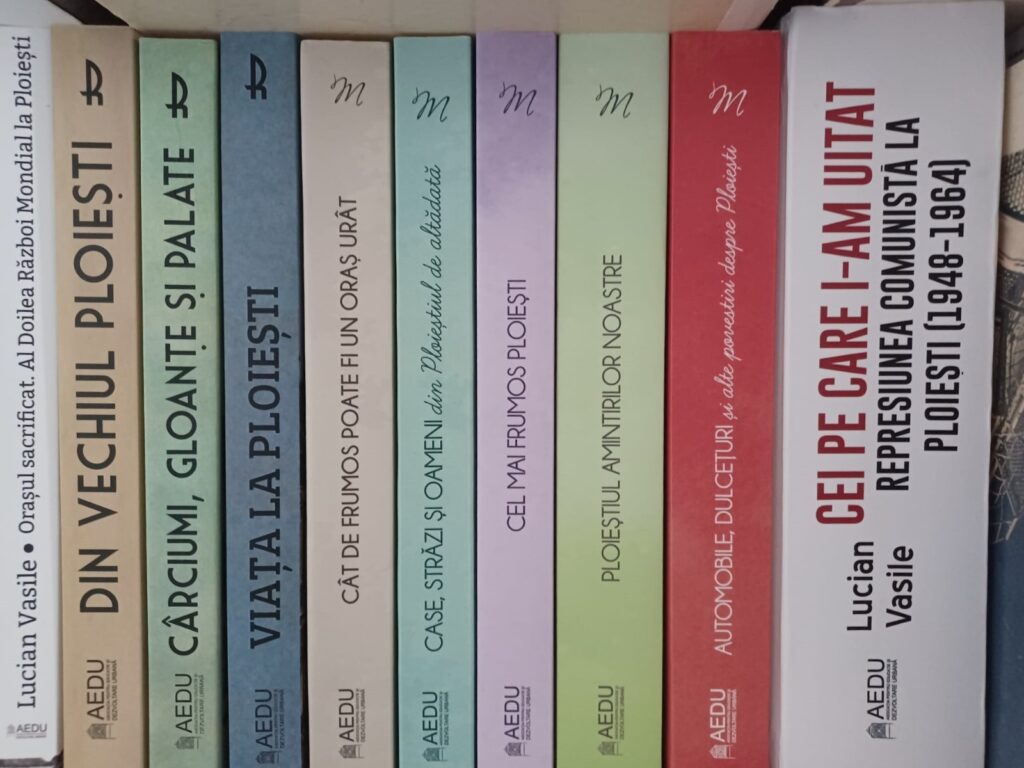

I would say that the biggest challenge was to carry from place to place dozens of boxes of books. I felt this in my back, therefore I ended up using a trolley. Beyond this problem, the financial aspect is worth mentioning: every book is a challenge itself because you need to make sure you sell it. Otherwise, you won’t have enough money for the book you’d like to release next. We are self-funded, so we need to come up with attractive and accessible (from a price point view) products, however, we must make sure we don’t fall short on the quality front. This is one of the advantages of a capitalist society. When it comes to publishing albums, it is even more challenging, because printing one is really costly; at least this is how it feels for a small NGO like AEDU. In order to sell it at an affordable price (because we all want our readers afford purchasing our book, don’t we?), the production costs have to be as low as they can. This means that the print run has to be bigger and, therefore, the overall cost would be higher as well. With regards to the first album, we managed to cover the cost ourselves, and it took us a while to recoup our investment. Releasing the second album was a bit more expensive; so we had to hold a crowdfunding campaign to partly cover the printing cost.

Every book is a challenge indeed, but also a source of joy and fulfilment. I feel a genuine satisfaction whenever I see the volumes I published through AEDU on the shelves. This is because I know how hard we worked on these interesting and valuable books, and also because it is through them that I recovered chapters of history which otherwise would have remained unexplored. One of the moments which brought me an immense personal satisfaction was when the son of a former political prisoner from Ploiești gave me a phone call to thank me for publishing his father’s story.

Last year you made your way to publishing a book through a publishing house. With Corint, you released The War of Spies. The Secret Actions of the Romanian Exile in the Early Years of Communism, which is based on your PhD thesis. How come you eventually chose to collaborate with a publishing house and why Corint?

Publishing a book on your own can be as fulfilling as it can be complicated because of the inherent limitations. The editorial project can grow only to a certain point, be it in terms of visibility, how far it can reach or even the way it’s perceived. For example, somebody gave me the impression that only the book I published with Corint is worth of being taken seriously. Nevertheless, this perspective puzzled me because, in essence, the book about the communist repression from Ploiești, published through AEDU, had nothing inferior to the one about spies, released by Corint. However, I do understand this stance. I also wanted to see how it is to work with a prestigious publishing house. I collaborated with Corint because I wanted my PhD thesis to be published by a publishing house holding the highest rank in the editorial classification; and at the moment in Romania there are only a few publishing houses of this kind. Furthermore, I had already collaborated with Corint in the past, as an external copy editor for two of their titles.

What are the differences between releasing a book through a publishing house and self-publishing it?

Releasing a book through a publishing house is similar to flying on a commercial plane: the author needs to understand that some essential aspects will be in the hands of other people and that they won’t be in full control anymore. For somebody who used to deal with all these stages themselves, from writing the book, to promoting it, along with dealing with the paperwork, well, it’s difficult to accept this partial renouncement.The way you feel this transition from self-publishing to collaborating with a publishing house depends on a variety of factors: first and foremost, what are the expectations of the author? What do they want, what’s their goal? Do they want to have their book released through a particular publishing house? Or they hope that collaborating with a publishing house would facilitate the progression of their book? Of course, the publishing house the author decides to work with is very important, because they are ultimately responsible for the manuscript, the cover they find suitable for the book, for how they promote it and so on. In addition, having your book released through a renowned publishing house can help you launch it at a big-scale book fair – this opportunity is somehow difficult to secure if you go to the self-publishing path.

At the same time, the publication of this book would not have been possible without the support of The Konrad Adenauer Foundation. I take the opportunity to thank them once again.

I talked to some of the authors I interviewed here about the importance of their involvement in promoting their books. How do you see this aspect, what’s your level of involvement in The War of Spies?

My main goal wasn’t to solely publish the book, but rather to get it to as many readers as possible, and to make the characters’ story known. Therefore I am willing to do as much as I can to promote it, giving that I see this aspect as one of the main responsibilities of the author. For example, I myself made the video for the launch I held at Gaudeamus literary festival, I was in charge of organizing the book launch from Ploiești, I sent out various press releases and so forth. They were an inherent part of the job, so I didn’t have any hesitations as these helped me promote the book. However, ideally there should be a synergy between the author and the publishing house; a mutual effort is beneficial to both parties.

At the book launches you had you talked about how you came up with this topic and how you ran your research for The War of Spies . Can you please share with us once again more details about it, touching upon how you managed to get to the sourses on which you based your work?

I was lucky. Back in 2015, whilst I was studying about the political prisoners executed at Jilava prison, I discovered some sort of identity card of one of the detainees, Gheorghe Șerbu, a high school teacher from Bucharest. He got arrested in 1950, sentenced to death for high treason (espionage) and executed in 1952. It was odd that a teacher would be sententenced to death for such thing, so I digged for his files. The first one I found was thin, it had only a few pages, and of no relevance. Shortly after that, in a few months, I got a call from CNSAS (The National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives), telling me that they found the criminal record of Gheorghe Șerbu (which included the investigation, the trial and his detention time) consisting of eight volumes. In that record I discovered the entire story of an espionage network from Romania, active from 1949 to 1950. This record helped me discover some relevant names of which I hadn’t known much at the time. The available information was limited, so I asked for their files as well. Within those I found other important names, other secret activities and so forth.

Along with the archives and the editorial works you used for your research, the interviews and the discussions you had with the relatives of the characters from your book represent an important contribution as well. It’s fascinating how you managed to get in contact with these people, and the way in which you turned their stories into palpable characters, in flesh and bone. Has the book published by Corint facilitated meeting relevant people?

I had meetings with key people towards the end of my PhD, therefore right before the publishing house received my manuscript. It was very interesting to find on Facebook the granddaughter of one of the most active secret agents of the Romanian exile. I knew more about her grandfather’s activity than she knew at the time, so I told her what I discovered in his record. I was also impressed to be contacted by the niece of one of the most important spies, who was in fact a double agent. I published his biography as part of the responsibilities of a PhD candidate, and the article was uploaded on an online database. Therefore, when the lady googled up her uncle’s name, she stumbled upon my article, so she reached me. I remember I was so excited that I couldn’t even reply to her on the same day; and what she knew about her uncle complemented perfectly what I knew about him at the time.

What are your plans for the future in terms of books about recent history?

I would like to write the biography of a secret agent whose lifestory exceeds any expectations. His story is so spectacular that it’s sometimes hard to believe that it was real.

What plans do you have with regards to a different passion of yours – the history of Ploiești?

I have quite a few ideas, but my free time is limited. There are some editorial projects I am currently working on in parallel, but it’s too early to discuss them.

Our bookcase is unequally split in two: your “half” and my “half.” What are the books that impressed you the most lately (from either side of the bookcase)?

No doubt the book I lately enjoyed the most is Diary of 66 , by Alexandra Furnea. Going back in time, I would like to shed some light on the memoirs of Radu Mărculescu (especially those written while he was imprisoned by the Soviets) and on The Lost Years by Jean Schafhutl. I also like the children’s books I have at home, which are intuitively placed on the other side of the bookcase. [Translated into English by Serena Marin.]

Main photo: © Horia Sârghi / Loredana Brătilă

The photos from the book launches are made by Sorin Petculescu