Interview conducted by Paul Florescu, after winning the Grand Prize at BEST Letters Colloquia, the 9th edition (Faculty of Letters – University of Bucharest, 13-14 May 2022)

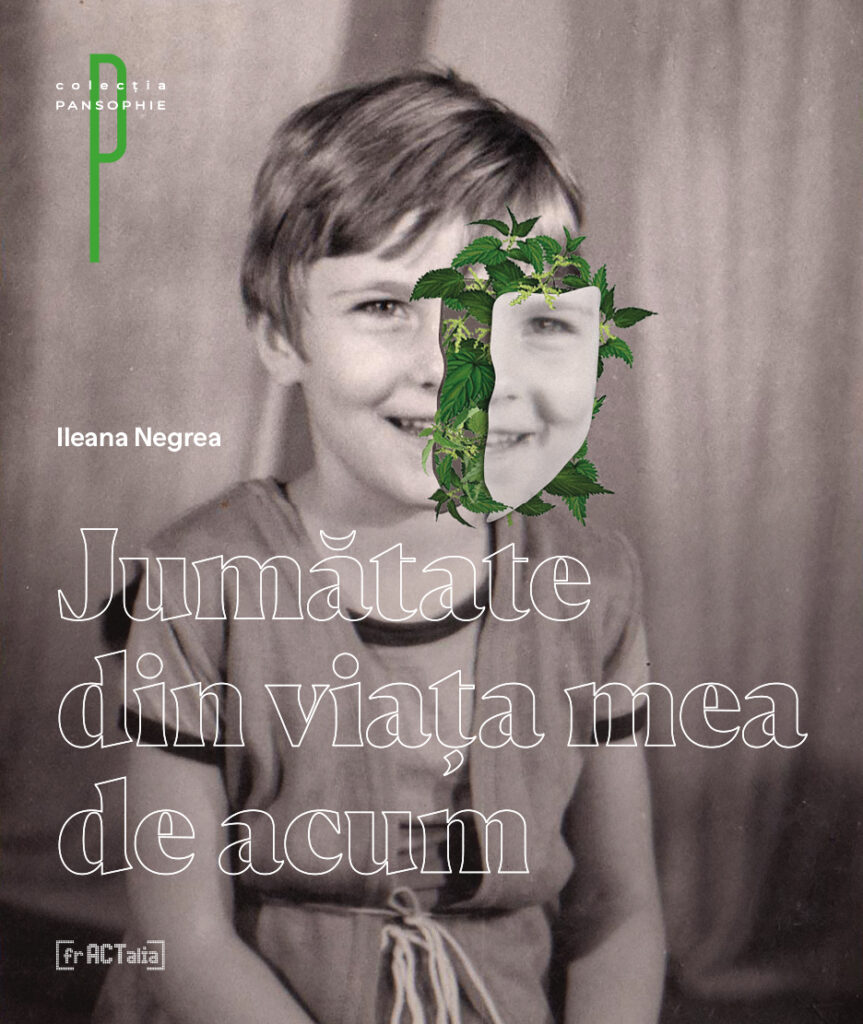

Ileana Negrea (b. 1984, Ploiești) graduated from the Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literatures in Bucharest. Out of a desire to create safe spaces, she organised poetry workshops. She believes that the political and the personal are not mutually exclusive. In 2021, her debut volume, Jumătate din viața mea de acum, which encapsulates both a personal and a community history, received the national award Mihai Eminescu.

Your debut volume, Jumătate din viața mea de acum [Half of My Life as of Now], published by FrACTalia last year, almost forces its reader into an intimate participation with an "ex-centric" sensibility and consciousness that the dominant culture condemns to a peripheral existence, in its attempts to suppress it as much as possible. Therefore, I had the impression that the volume (also) represents a militant cry against systemie injustices and, equally, for the authenticunderstanding of what is "different", "foreign", and takes place in its own space, or the "right to living", which ultimately demands that it no longer be demonized and expelled. Your poetry becomes a medium of self-communication, of exorcising trauma, of excavating social realities that inhibit and mutilate a person's true identity. In nooIn no other recent volume of poetry have I encountered such a vehement violation of the aestheticizing conception, such a radical shattering of the traditional disjunction between the "lyrical subject" and the personal self, between the fictional self and the author. What do you think are the functions of a personally assumed speech and such direct language that refuses metaphorical status?

I don't know what to say about this total merging of the personal self and the lyrical self. It seems very dangerous to me. For example, after the awarding of the Eminescu prize, the world felt validated to attack the author based on the confessions in the poem. I think that, on some level, we do fictionalize ourselves to some extent through writing, even when we stay connected to the truth, we somehow move away from the biographical.

From my point of view, an assumed speech is a personal speech. And this is where your revelation as a human being, small, imperfect and often in pain, comes in, as a creative function of connection and intimacy with the reader. I believe that the presence of detail, even if it does not lead to the reader's identification with the text, creates the premise of a relationship, of a mirroring of the content and of an acceptance of one's own humanity. By humanity here I mean susceptibility to failure and suffering, but also emotional fragility and, at the same time, resilience. It's as if we were talking now: If I make myself vulnerable in front of you, by telling you about myself, it is quite possible that you will do the same, not necessarily to me, but to yourself.

It is a language that is meant to be performative, rather than metaphorical; a language that wants a change in the world and, as long as the text reaches the right people, it can make it happen.

Another function could be to activate the empathic "muscle". That is because empathy is an exercise, a practice that requires safe spaces and examples. This is what I'm trying to create. I free myself from my own story by writing it, rewriting it and editing it (which offers a lot of power, we empower ourselves by controlling our own narrative, a privilege we are lacking in everyday life), I rebalance myself, I search for my voice again and again, hopefully, calling for other testimonies in a non-judgmental and non-exclusive space.

One of your texts begins with the line "The reign of aesthetics ends with me", and concludes with "The reign of aesthetics ends with us". Who is this "us"?

This "us" aims to be broad, therefore anyone who does not currently feel represented is included here, but it is also a natural continuation of the few names mentioned earlier in the text.

Walt Whitman scria în Song of Myself „I am large, I contain multitudes”, încercând să circumscrie în cadrul unui discurs poetic puternic subiectivist discursurile marginalizaților, ale celor fără voce sau a căror voce este amuțită de societate, oscilând între experiența subiectivă și cea comunitară, între I and we. "Multitudes” can also mean multiple identities, different facets of a whole. As you state in your texts, you are at the intersection of multiple identities, as well as of political and social practices: Activist, queer, mad person, feminist, anti-capitalist. All of these are reflected in the themes of your volume, in the militant tone that most of the poems share, in the extra-aesthetic stakes of Jumătate din viața mea de acum. How would you define activist literature? Is it the space where "I" meets "us" and bears a personal testimony to the collective experience of queer, mad people?

It is a literature that does not exist in a precious vacuum, that is aware that every "I" is, without exception, part of a "we". When you become truly self-aware you realise that you are a result of socio-politico-cultural circumstances, that you are partly hazard, partly history. It is enough to pay attention to the details of your own life to realize that you are part of many different groups and systems.

For me, activist literature did not start from a general impulse to somehow make a change in the world, but from me, from the particularities of my existence, from what I wanted, from purely personal needs. By observing them, and therefore by observing myself, I also glimpsed the bigger picture, I was able to formulate some values etc. I think the primary work in both activism and literature is the work with yourself. From there, you can build further. Otherwise it's chaotic and painful and discontinuous.

So does engaged poetry deny its self-reflexive and solipsistic dimension in order to represent social reality?

As I was saying before, the so-called engaged poetry is primarily self-reflexive. Not solipsistic, we don't live alone.

Is there a link between the "reign of aesthetics" and (patriarchal) authority?

Of course. I'm referring to pure aesthetics here, I think (even) my poetry is, in fact, aesthetic :). The question is what we actually mean by "aesthetics", who defines it. I will also mention the use of double standards: What is considered aesthetic in a majority individual, does not apply to me.

To what extent does the double standardapply to literature written by women and to literature written by queer people? Do you think that "obscenities" found in men's writing are received differently and/or are more acceptable than those found in literature written by women? What is the difference?

Yes, iin a completely different way. It depends on the context, though. If it's not one that creates a relationship of submission, of acceptance of the status quo, then it really becomes a problem. When we (re)write our own sexuality, for example. When we show agency and ownership. When we use the word we have been silenced to for centuries in a metaphor of war, of violence, a practice that does not belong to us, to self-empower ourselves. When we represent a danger to order and beauty. Again, let us remember who decided what order and beauty are.

Do you think that, in Romania, the value of a literary text is invalidated by the author's ideological "partisanship"?

Doar dacă acela este unul care îndeamnă la ură. Nu reușesc neam să înțeleg fobia unora de corectitudine politică. Cum poți vedea ceva nociv în iubire, în drepturi și dreptate pentru toți. A, că îți simți amenințat echilibrul pe care îl stăpânești de la începutul lumii? Fă terapie atunci. Prin scris, nu neapărat cu un profesionist, e mai la îndemână. Dar nu te panica, poți sta în continuare drept într-o lume în care toți avem dreptul să stăm în picioare.

Jumătate din viața mea de acum was published by FrACTalia, a left-leaning political publishing house that "supports feminist and intersectional voices and texts", publishes queer and feminist theory, and supports social movements, such as environmentalism and decolonial practices. To what extent has the policy of this publishing house, the body of translated texts, the anthologies published, the mission it has taken on convinced you that the manuscript will be properly cared for, understood, appreciated and edited? Does the policy of a publishing house matter more to you than its prestige?

Yes, the way I know that my text will be received, the fact that I know or I can, at least, hope that it will not be aestheticized and alienated from me is very important. And frACTalia had already published very talented female poets. For me, it did have "prestige". Also, my book was nominated for almost all literary awards and sold decently for a book of poetry. Honestly, if you're on the verge of your debut, don't wait for validation through the publishing house’s prestige. The book will somehow make its own way.

How did the relationship with the book's editors go?

It was a very good, cooperative, horizontal, even comradely relationship.

Have you ever had your expressions censored, given that this practice has a (sad) recent history?

At the Eminescu Prize, that's it.

What will the "New Romanian Canon" look like and how do you think the "de-canonisation" process will evolve? What role does Cenaclul X [Literary Circle X] play in this process?

I'm no longer part of Literary Circle X. I tend to form micro-communities from which I disappear afterwards. It's a behavioural pattern that I don't yet know how to coexist with. I'm working on that. I hope the cenacle helps, there are already many names from the cenacle who have debuted or who are forthcoming. We put out an anthology together, Adăposturi [Shelters]. A second, Luminișuri [Glades]. , is next. But to me, the therapeutic role of the cenacle is essential: Of belonging, of supporting self-identification, of refining one's own voice by accessing others like it. In regards to a new canon and a possible de-canonisation, I will refrain myself from commenting. It is a long, arduous process, in which critics, publishers, event organisers and the public itself are more likely to matter.

Does the concept of "canon" need to be overcome?

I think so. But we have this deep-rooted need for adulation, classification, comparison. So it doesn't seem feasible to me.

What does a "war machine" look like, one that does not assume the violence, the machismo, the privilege of the war machines present in majority & authoritarian discourse, and how can we build it?

Well... Writing. Practicing it in spite of ourselves, the way we were raised, respectable and good, obedient, unquestioningly honouring all that is norm and normal in art and society. And then in spite of our detractors, those who throw the mud they are made of at us, and for whom I am genuinely worried and sad. Because they only see their own story. And because they act out of fear. And that fear of theirs perpetuates fear. It keeps us in our place and if we dare to come forward it humiliates us. I dream of a world built on emotionally processed, integrated fear and shame.

I think we also need the net of the communities we belong to or at least someone warm, an empathetic near-witness, when we venture into our literary world. IIn different eras, also partly in my home, it was said that the woman/child should not be heard, only seen. Now, post online trash, I would like to be invisible, to be left with my voice only, with my message. Let's not forget that behind the author is the human being (not a demiurge, as we learned at the Romanian literature class in school). Let's do our own emotional work before coming up with cruel verdicts. It's easier to prevent than to cure.

[Photo from Ileana Negrea's archive.] [Translated into English by Simina Barna.]

Paul Florescu (b. 2000, Suceava) is a student at the Faculty of Letters, University of Bucharest, in the Master's programme Literary Studies. He participated in the national colloquium Bucharest Student Letters Colloquia with two papers: on Fernando Pessoa's poetry in 2021, and on Sylvia Plath's poetry in 2022. He is interested in cultural studies, philosophy, identity politics, film and literature. He is gradually discovering contemporary poetry.