Alex Ciorogar is the founder and manager of OMG Publishing House, the director of Echinox magazine and assistant professor at the Faculty of Letters of Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca. He received a PhD in Philology, wrote book reviews for ten years, published scientific studies both in Romania and abroad and co-authored a couple of book on Dimitrie Cantemir.

Does a T0 point of your career as a reader exist? What about a book that led you on this path?

Although I haven’t really reflected on that moment, I think that it still exists. The truth is that I didn’t like reading in Romanian and I got to more serious readings through the fascination that I was nurturing for Comic Books. I found somehow, through a miracle, a graphic novel about Wolverine (from the X-Men comic book series) in a bookshop downtown in Mediaș where I would go on holidays to my paternal grandparents. And I bugged my parents to buy it then and I read it countless times. It was a graphic novel, it had noirillustrations, so to say. I can’t remember how old I was, but I had learnt English from the living room TV (a color Samsung) that was tuned nonstop on Cartoon Network. Well, only after that first reading moment I began to inspect our bookcase from home, my mother being a Romanian language and literature teacher. That’s how I discovered that we had in fact Hemingway on the shelf too, A Farewell to Arms. I thought it to be the best novel in the world, of course. And I think that’s the reason I still have a soft spot for the American novelist.

In 2019, when you launched OMG publishing house, poetry seemed to have gotten out of the niche in which it stood for many decades, becoming an Instagramable thing, both abroad (if I’m thinking of the huge success that Rupi Kaur had with milk and honey – at the agency we sold the rights in about ten territories in the East of Europe) and in our country (it comes to my mind the poetry Nocturnes organized by ARCEN, most of the times sell-out). The fact that you began with OHMYGODPOETRY was an influence of these changes or a coincidence?

It was a coincidence. The Kaur phenomenon had exploded a couple of years before. I think poetry was always an Instagramable thing, as you say. Only we weren’t using this soft (or it simply didn’t exist yet). I would only like to mention that one of the most important characteristics of poetry is that it can be easily transported from an environment to another. No other form, no other literary genre is capable of that. More interesting it’s the fact that this mobility is not systematically studied in the academic world, even though the quality is there since forever, I would say. These material supports or, if you want, delivery systems are very important and represent a part of poetry’s life and structure. The poetry nocturnes are a good example in this sense. We should fight a bit against the prejudices that we actually have about the forms, places and environments in which poetry shows up more or less unexpectedly in our lives.

How did you manage to coagulate the nucleus of the publishing house? I’m thinking not only of authors and editors (the last ones being presented on the site, which seems to me really cool & professional), but of the administrative staff which forms, I think, the skeleton of this organism, from the driver to the accountants.

The nucleus of the publishing house is based on friendships. It’s not a big publishing house and the luck was on my side for having an entourage formed of capable people that at the same time are willing to do what it takes. Money is scarce and the work is voluntary. I think in the end we’re all doing it out of passion. First of all, I want us to publish cool books. Not only for their content, but for how these objects look too. But there are poet friends too, such as Valeriu A. Cuc, who donated generous amounts of money to the publishing house. And that happened in crucial moments when we got stuck. Coming back to the question, I think there are many roles played in essence by the same person. Of course that certain services must be externalized, there’s no other way.

„An academic, a designer and a book seller walk into a bar”, as you said in an interview on the beginnings of OMG. How did you find the Romanian editorial market once you entered it comparing to the way you were seeing it before?

The editorial market is pretty wild in our country. You’re basically fighting with a couple of mammoths. The important thing is that OMG created a new audience and is offering to the readers something that simply didn’t exist before. It’s odder to me that, although they have the necessary resources, the big publishing houses don’t do what they should do. From advertising to the way in which they engage the readers in international circuits and mechanisms.

Have you had an expectation that was exceeded? In worse or better?

The way in which the audience relates to the book is very strange. We buy books from book stores because we like those places. We like to walk in front of the shelves, touch the books, lean our head on the side so we could read the spine. We glance at what others are browsing. And there should be included all kinds of others behaviours. It seems pretty hard to me, considering all of this, to sell books online. Of course that when you know what you want, you place the order without thinking twice. But when you try something new you’d kind of like to see it first. And then there’s the delivery issue too. Of course that some of these problems could be solved if we put more emphasis on electronic books. But from my experience, when we like very much a book we buy it in printed format too. I would like for OMG to offer the readers small luxurious experiences. I’d like that when they touch the book and read it to feel they have in hands a product of the highest quality.

How did you manage to enter the book store chains? The distribution part can be the most difficult one from a publishing house’s life.

It was difficult, but it was easy too. It was difficult in the beginning because it’s really problematic to make it to the Cărturești bookstores, for example. It’s a corporation, even though it doesn’t look like it. It was easy because Humanitas, for example, wanted this collaboration (which I eventually turned down). I succeeded in entering those bookstores because I know the ones that can facilitate this kind of access too, as well as through recommendations.

You’re publishing perhaps the freshest literature on the fiction & literary studies segment. What communication and advertising tools did you adapt (you were saying in an interview that you applied methods from the company you worked at) or even invented?

Thank you. I’m very glad you’re saying that. I think I learnt a lot along the way too. But the multinational company for which I’ve worked helped me very much for sure in that sense. I think that organizational culture can be easily applied in any work environment, especially when we talk about team work. I don’t see why publishing houses or authors would avoid nowadays advertising on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram or even TikTok. Everything is about networking. I’ve had the luck of having some very talented people too.

How is the relationship with writers when it comes to working on the text? How do you negotiate to end up with the best possible alternative?

It depends on the writer. I’ve had situations when I simply didn’t feel the need to interfere – I think it was the case with Tudor Pop’s book. There have been other collaborations when I interfered only on a proofreading level. However, there have been volumes that I’ve worked really hard on, and not just me. For example, I remember that in Timotei Drob’s book I rewrote a whole stanza, and Alex Văsieș did the same (even though with another poem). But Timotei gave us free hand. Therefore, I repeat, it depends only on the writer. However, most of the times it’s only about suggestions which I’m making or which we’re making and then the author accepts or rejects them. We don’t force anybody to do something if they don’t agree with that thing. It’s, indeed, a negotiation. Other writers have this exact request – I would like the manuscript to be copy-edited, retouched, corrected and so on, even though the texts are already good.

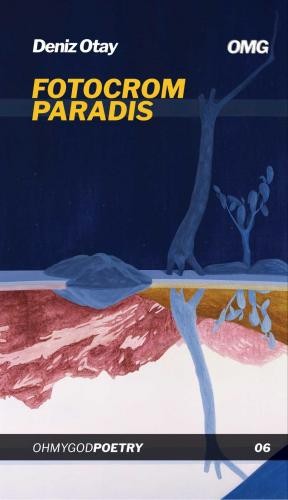

Deniz Otay won the National Poetry Prize for debut. What impact do Romanian literary prizes have on the sale of a book?

I think that it’s obvious for everyone that prizes automatically attract sales. However, Deniz Otay was selling good before the prize too. It’s an excellent poetry book.

You’ve been for a while now the director of Echinox magazine from Cluj-Napoca. You put together a young and very young team, which can be observed by the content and the new design of the magazine. What are the mechanisms through which a long existent magazine can reinvent itself, adapt and stay relevant in a changing (editorial) world?

Thank you again. And thank you on behalf of the editorial office. I think it’s about transforming the magazine into a small cultural and economic society, on one hand, and on the other hand, transforming it into a community in which communication and collaboration is free and open. We’re always looking for new collaborators. Our world is global and digital. The magazine can only be the same.

In an interview from a couple of years ago Ștefan Baghiu said that a first step in stabilizing the editorial world in our country is the developing of a functional distribution system for literary magazines. In the meantime, he became the secretary of the editorial office at Transilvaniaand you began to run Echinox. Can you take part from these positions at the construction of this system? What would it imply?

Indeed, literary magazines don’t have a functional distribution system. In the case of Echinoxmagazine, the reason for which this is happening is that we’re depending financially on the Babeș-Bolyai University. Because they’re a public institution, this entity can’t conclude distribution contracts with bookstores because they can’t justify the sale and the profit.

Echinox is present in two great bookstore chains, Cărturești and Librarium. Do these collaborations reflect in selling too?

Revista Echinox can be found now in these two big chains because the respective issue – the revamped one that marks my directorial – was financed from our own funds (and not through University). In these circumstances, the magazine has done surprisingly good, I would say.

Now that you can check in your own accountancy, what influence do the book reviews (still) have in the popularization of a title or author and, most importantly, do they reflect on sales?

I don’t have any kind of statistics in that sense, but it seems to me that sales don’t depend on these book reviews anymore. Of course that any material contributes to the popularity of a title or author, but I think sales don’t depend that much on that institution and the review practice anymore. An exception can maybe represent the literary history studies and literary criticism. I think things there go on in the same way from some kind of inertia. Way more influential are now the small reviews on Goodreads or the reading blogs and other such popularization forms.

You’ve been on both sides: what’s harder – reforming an institution or starting a new one from scratch?

It’s absolutely harder to reform an institution than create a new one. When you start from scratch you fight only with yourself.

Besides being a cultural product, a publishing house is a business which, in order to work, has to be able to cover the costs at the end of the month and, with a little bit of luck, to have profit too. Rewording a phrase often heard among writers, can a publishing house survive from writing and publishing?

I think a publishing house can do that. OMG can’t do it yet, unfortunately, but I’m sure that day will come.

Many of the published writers made their debut at OMG. What are the cards upon the publishing house’s sleeve to keep them in its portfolio, not to lose them in favour of another publishing house?

The reason writers want to publish at OMG is the same reason readers are interested in our books. As you were saying above, the publishing house has a fresh air and it’s simply cooler than the others. I’m not thinking of our authors in terms of property. I mean I don’t necessarily feel that I lose someone if they collaborate with another publishing house – I think in the end we’re all working for the same Romanian literature. I think the authors make those choices based on what a publishing house represents, based on its symbolic capital and, of course, based on the people behind it.

But the other way around, how did you attract writers that were already publishing at other publishing houses?

I think that people want to publish at OMG because they trust us. I, for example, made a name for myself writing book reviews for 10 years. I know the literary world. I know the poetry field. The same thing can be said about the OMG team too – we’re talking about poets, critics and academics with very much valuable experience. We’re all working together for the authors that want to collaborate with us.

In the opinion of many actors in the industry, one of the lacunae of the book market in our country is the lack of literary agents, seen in the roles they play in the Anglo-Saxon space, especially in the USA: the bond between an author and the publishing house and the ambassador of the books in the other territories. From your experience with the writers you’ve published, do you think the Romanian book market is ready to assimilate this kind of mediator between authors and the publishing houses?

I don’t think it’s ready, but I think this is necessary and I would like OMG to thrive in the future in this kind of literary agency too.

Another discontent circulating in the editorial field is the poor representation of Romanian writers abroad. A spotted cause for that being, again, the lack of these agents. As an editor, cultural magazine manager and reader, what do you think are the exportable valences of Romanian literature? Or what do we lack?

That’s a very complicated question which deserves an entire debate. The Romanian literature, even though not in its entirety, is as exportable as any other literature. We don’t lack anything in this sense. We rather lack the solid circuits that enable this export. But thing have been already moving for a while in that regard too.

What is the bright perspective of an editor?

:) I think the hope lays in the fact that, in time, the published books will mark a small historical event in this area’s cultural history. (Translated into English by Silvia Codescu)