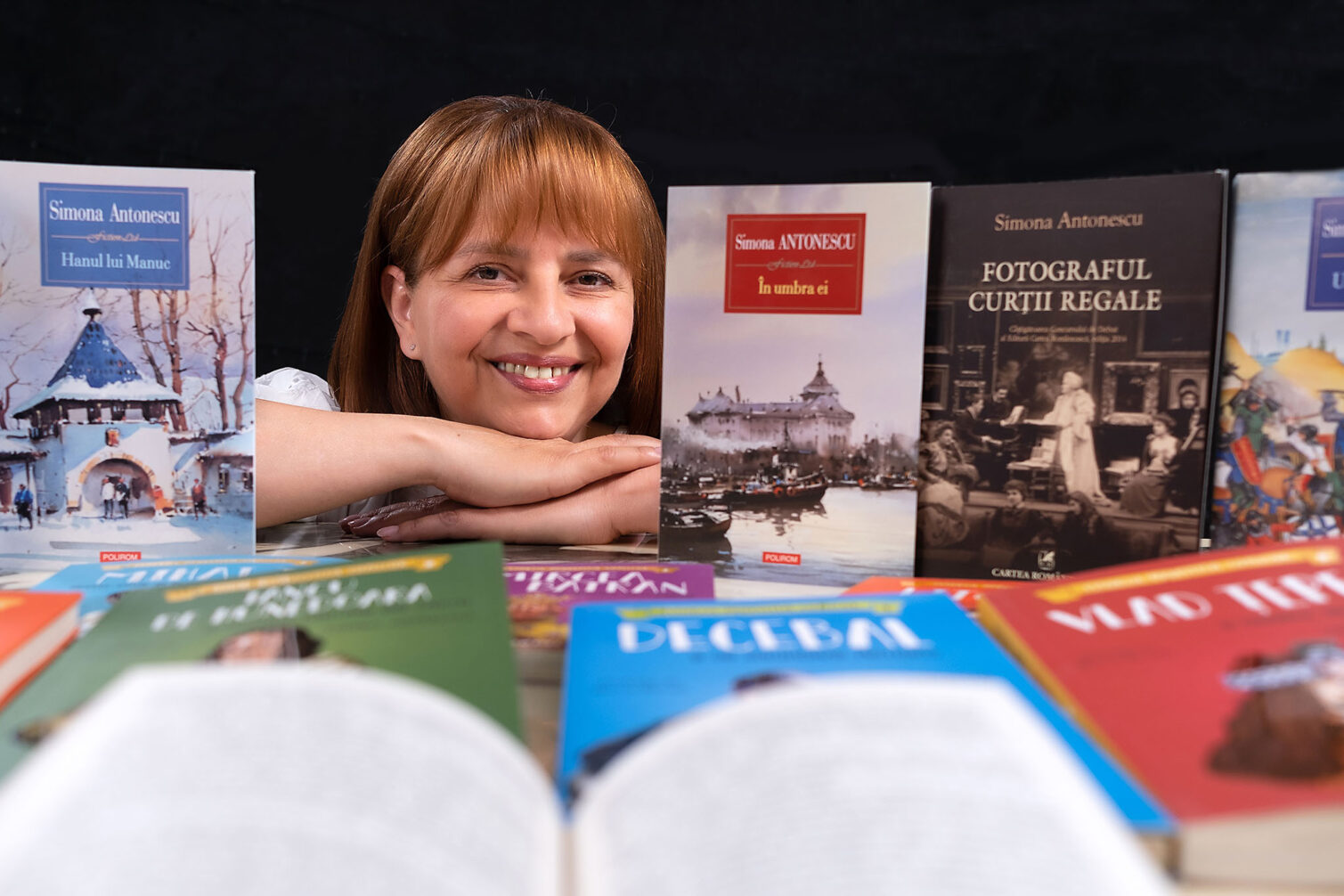

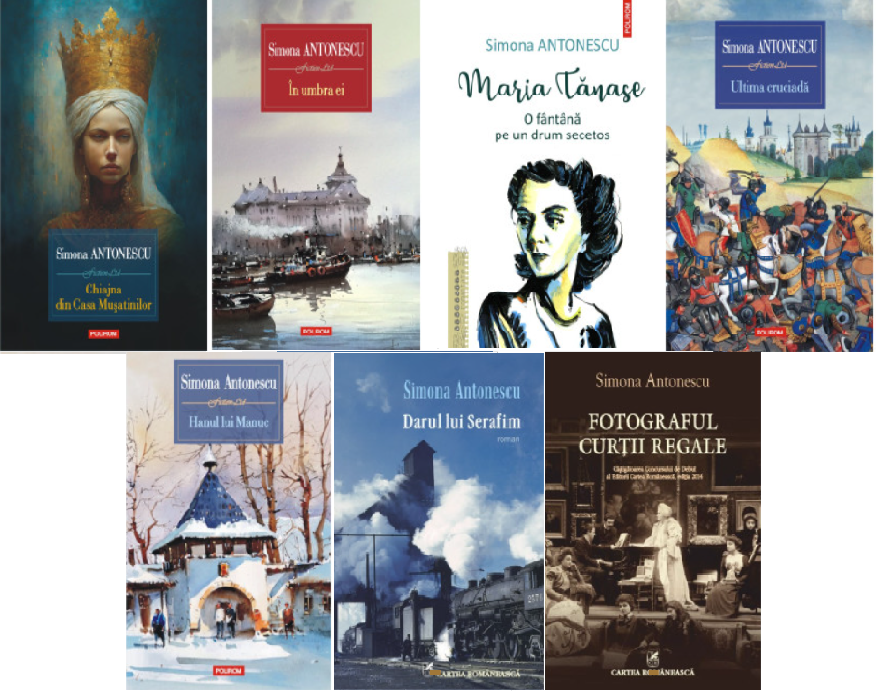

Simona Antonescu is a writer, the one who reopened the taste for historical fiction in contemporary Romanian literature. She made her debut in 2015 with The Photographer of the Royal Court, after winning the Polirom Debut Contest. This was followed, published by the same publishing house, by the novels Seraphim's Gift (2016), Manuc's Inn (2017), The Last Crusade (2019), Maria Tănase. A Fountain on a Dry Road (2019) - part of the series of romanticised biographies published by Polirom, In Her Shadow (2021) and Chiajna of the House of Mușat Chiajna of the House of Mușat (2023), as well as the series History Told to Children, published by Nemi. Appreciated by young and old readers, Simona Antonescu proves through all her books that she is a wonderful storyteller.

Cinnamon, ginger, rustling leather skirts and hunting boots. These are some of the sensory details that open up the world of your latest novel, Chiajna of the House of Mușat. And which are bound to stay with you long after you finish the book. What kind of syncretic memories do you have of your early reading life?

It's hard to discern today which memories from real sensory life I actually picked up from childhood reading. There was a time, between the ages of 8 and 12-13, when I was learning about the world more from books than from what was happening to me. Life around me seemed much duller and less challenging than that in books. On the other hand, when you say "my early reading life", my thoughts include the beginning of my life as a listener of stories and histories, the ones my grandparents on my mother's side raised us with. My grandmother told me, for example, about a first love from her own childhood, a boy named Zamfir, outside it was springtime in my grandmother's story, and I forever mixed that boy's name with the smell of hyacinths. The name Zamfir will forever smell, to me, of hyacinths.

Just as the name Fram smells to me of rotten planks, wet hay and snow, from Cezar Petrescu's description of the Strukti circus, and very vaguely of fruit candy, because somewhere in Fram the Polar Bear, there is a little boy who receives candy from Fram.

Later I would read the Pardaillan Knights series and Paul Féval's books, munching on kilos of apples. There was a time when I was eating apples non-stop, and their taste is, today, for me, the taste of cape and sword adventures.

But the true sensory memories I gleaned from the books have forever melted into the content of all memories. It wasn't until late in adulthood that I began to stop my reading where the doppelgangers of the senses in my brain perceived something - a smell, a texture, a taste - to dissect that phrase, to understand how that writer made magic.

The court of Petru Rareș in Moldavia, of Mircea Vodă in Wallachia and Istanbul in the second half of the 16th century are some of the places you bring to life in the new novel, completing with great verisimilitude what historiography has failed to find so far. How do these pieces of worlds appear (to you) as you fill in the blanks?

I'll try to give as plastic an explanation as possible, because I want you to understand how easy it is. I've never considered that I have any merit at this point. It goes like this: I'm walking around Florence on holiday, I'm walking through Piazza della Signoria, I'm surrounded exclusively by buildings that are hundreds of years old, only the people are from the present. At a time like this (when all around me is history) I wonder: what did this place look like when they had just finished building it? I make no further effort, but Piazza della Signoria is populated with cinnamon and ginger sold by female merchants, painters from the guilds of red and blue, Venetian lancers with coloured feathers at the tips of their spears, and from above, Cosimo de Medici looks down on us all. The sensation is akin to the moment when, say, Dune-Part Two begins on a big screen next to you: can you still focus on the reality around you? Not really, because you're suddenly focused elsewhere.

All that remains for me to do is to have the patience to look carefully, to investigate all my senses: how does it smell? What can I hear in the distance? There is a female merchant, in the farthest corner of the market. What does the fig she bites taste like? All I do is stand there and be part of that world.

The novel follows a chronological route, even the chapters are clearly marked with some of the landmark years of Chiajna's destiny. What do the book's ins and outs look like, the science behind it? Did you work with charts, diagrams, graphs? Maybe all of them together?

All of them together and more on top. I had several time axes, a main one, on which I marked the major events in Chiajna's life (her mother's death, her exile when she was just a child, her marriage, etc.) and a few secondary ones, fragments of time that I took out separately so that I could detail on them all the little events, even the fictional ones: the war with her brothers over the cats, the schooling of Petru Rareș's barber or the stories of the freshwater robbers who stopped the salt rafts on the Someș river to rob them.

I then had lists of all the rulers of Wallachia for about 70 years, to understand how those changes of rulers took place and how serious the situation was (it was very serious, they changed every year or two). I had drawn my own family trees for the Mușats, the Drăculești and the Craiovești. In my variants women also appeared, so that I got used to using the different degrees of kinship in the novel: Chiajna easily says "my cousin", "my aunt". Which is not easy, given that her cousins and aunts belonged to rival houses.

For all the battles that appear in the novel I had diagrams of where they took place, i.e. I simply drew them, noted details of the field - lakes, marshes, forest edges, distance from the nearest village. These are entirely fictitious, unfortunately no details of the battles of Mircea the Shepherd and Chiajna have been preserved at all. But I needed these little maps, so that I could write those chapters with a steady hand, guide myself and give precise details.

I make character sheets. I really do. I can understand that it's slightly outdated, but it helps me. They're totally atypical sheets, I write down not how the character is, but how their enemy sees them and how their friend sees them. That's how I try to bring the information into the book: I don't say how the character is, but how those who love them and those who are their enemies see them. I add verbal tics, repetitive gestures, fears that change their behaviour. I don't think I’ve ever written in a character sheet what colour their hair and eyes were, how tall they were and how old they were. That's not what I'm interested in.

I had stacks and stacks of those big post-it notes, the largest size, on which I had written, over time, all sorts of scrappy ideas that had appeared long before their turn in the book. For example, the phrase "Let's go, let's go, that damn princess! Is that a princess?" (uttered, in the novel, by a boy from the fortress of Ciceu) had been on a note for a long time. I didn't have the character yet, but I badly needed something or someone to put Chiajna in a humiliating situation. One of the most enduring notes was the one on which I had written: 'a dead tree, standing up, stretched out its single branch, slicing the sky in two like a black bolt of lightning' - it was an image I had seen around Cluj from a hotel terrace, a withered tree, stubbornly refusing to fall. There was something beautiful and sad about it, it made you feel guilty for liking its pain. For a long time, I couldn't find a place for those words in the book, couldn't find a moment with that atmosphere.

Also part of the nets you are talking about are the two large rafts, two Styrofoam boards on which I had built the action, made of coloured notes attached with drawing pins. On the blue row there were the great events of European history, underneath, on the yellow row, there were the simultaneous events in Wallachia, with pink the same, but fictional this time.

Although the heroine of the novel, Chiajna stands alongside many other well-highlighted characters that you can't pass by indifferently. Anghel, Marula, Lăcustă the gardener, Roxelana, the sultan’s wife, are some of them. Which of these was too stubborn and kept running from being captured on a page? Or which, on the contrary, would have liked to get ahead of everyone else and seize the novel, perhaps to have its own spin-off in the future?

Of them all, Marula had a strong tendency to hog the story. I enjoyed writing about Lăcustă the gardener, but he had a more restrained attitude. I knew even before I started writing what his place would be, and he seemed to accept it. Unlike Marula, who I found myself thinking about at the most inopportune times, when I was writing chapters where she had no business.

I had a bit of trouble with Mircea the Shepeherd. I could say that he didn't let himself be reduced to a page. In order for the novel not to fall into a predictable melodrama, in which a woman like no other in the world takes over and does what armies of men have never done before her, I knew I needed a strong Mircea. Maybe even stronger than Chiajna. A personality to stand up to her and balance everything she hadn't yet done, but was going to do. If you remember, in the early scenes Mircea the Shepherd is taciturn, appearing hidden under that impetuous helmet and not saying a word. Because I couldn't catch him yet. It's the same feeling you get when you're in front of a stranger. As a character, he remained silent until I realised that he must have some tormented sort of unutterable love for Chiajna, which shamed him. It's only at this point that the character lightens up a bit and we see him.

You say at one point that you've always had a "head full of characters". When a new book project is getting off the ground and gaining momentum, who comes first - the characters or the story and the world they will create?

The characters always come first. And as a reader I look for the same thing: it's the character building that draws me in, that makes me admire the book I'm reading or bores me. I don't know of any good story that has characters second. After the characters what comes, for me, is the atmosphere, the world that gives the characters credibility. Let's put it this way: the characters are the ship with the crew on board, and the atmosphere, the world of this ship, is the sea in which it floats. The story, the action itself, is the ship's journey at sea. Does it matter in which direction it goes? If you ask me, not really, just make it go, make it go through adventures, break its mast, rip its sails, so we can see what the crew is doing, see them working together to keep the ship at sea. No matter where they go.

You have stated in many interviews that you write on weekends and holidays. Do you have a ritual you follow? Or a set of good habits you've refined over time?

To stick with the above comparison for a moment, the one best practice is that on Saturday mornings I go out on the deck, dive into the waves and don't come out until it's dark. I swim day-light, with a joy I find hard to describe. I'm an early riser in general, but on the days I'm writing I wake with anticipation.

The first steps of a writing day are: shower, coffee, phone on mute, check the stack of post-it notes, from which I choose 2-3 and put them on my desk in front of me to use that day, check God knows what maps or sketches, re-read the last page I wrote and continue. I read a Hemingway confession many, many years ago that he never wrote all the way through until he finished the ideas he had in his head. He always stopped at a point where his inspiration was strained, that is, he knew exactly what the next sentences were. That way, the next day he'd resume in force, eliminate that staring at the ceiling. It works perfectly.

At our most recent meeting, you mentioned that you have over ten folders of project ideas on your computer. How do these drafts emerge and how do you select the one that will become your new book?

There is a folder called "Books not yet written". I thought it was funny to leave that "yet" in there too, seeing it amuses me. The folder was born before I wrote the book I debuted with, The Photographer of the Royal Court, so it contains a lot of topics that appealed to me at the time, when I would write but couldn't decide what. In the meantime, I've added other subjects, perhaps not quite as random as the first ones were. Chiajna also lived in this folder for a while. It encompasses everything, it reminds me of an antique bazaar, it's a very vivid term in English, garage sale. There are paintings from hundreds of years ago, old photographs, contemporary photographs, links to God knows what stories that fired my imagination at some point, files in which I sketched the path of some character, even some historical figures. Treasures.

It's hard for me to explain how I make the selection. Probably because I don't really feel like choosing.

Turning to your relationship with the editors of your books, how permissive are you with their suggestions, how do you negotiate changes to the text? Do you have any special memories in this regard? Perhaps a more heated negotiation or a long-delayed compromise?

I think I'm quite difficult at these negotiations. I hope I'm wrong. I don't think anyone would call them fierce, because the discussions are kept on a very polite level, but when several emails are exchanged over a single sentence, it's clear that neither side wants to give up. Arguments are usually made by each side. One point that I can't explain at all, and which for me hangs heavy, i.e. I'd sacrifice a lot for it, is the balance of the sentence, that rhythm of the song being sung. The argument that I know I'd have to give in to is logic, meaning you can't sacrifice the logic of the phrase for the sake of rhythm. Sometimes it's hard for me to admit that.

Most of your book covers seem to have become trademarks of the literature you write. How involved are you in the way they look? How much do you get involved in other details of the book as an object, from print runs to paper and so on?

I get very involved in the choice of cover, but that's the only point in the whole process of getting the book published. Every time I send in the manuscript and it's accepted, so we start working on the book, I have a few ideas for the cover prepared, which I send in. I know how I'd like it to look and I'm very prepared to explain that. I then test the different versions that the publishers suggest, send them to friends and do a sort of secret survey, like a little market research.

I never get involved in the print run, the type of paper or other details.

I have talked in interviews published here about the importance of the writer's involvement in promoting his own books. I remember the chocolates in the wrapper with the cover image present at some of your book launches. How much do you accompany a book after its release, how much initiative do you have or how does the collaboration with the publisher's promotion team go?

I like to get involved; in fact, I like to play a lot. All those contests I do on Facebook, with guessing the title or gradually revealing bits and pieces, are my own. The publisher responded immediately each time, meaning I said I needed 5 copies for something I wanted to do on Facebook, and I got them. The idea of the chocolate was also mine, I also found the supplier, unfortunately after Covid things didn't really connect, it was a small company and probably affected.

After the book comes out and I get launch proposals from the publisher, I usually take time off and hit the bookstores. With Chiajna, I've had the joy of receiving many invitations from schools and teachers of Romanian language.

Each new book gets attention from critics, cultural journalists, bloggers and vloggers. Are you following what's being written about your books? Do these impressions impact you or the way you write your next books?

Yes, I follow what is written about my books. It can't not have an impact, because the feeling any writer has about their books is deeply parental. It's very easy to confuse things and fall into the trap of considering a negative opinion of a book as a negative opinion of yourself. In fact, there, in that opinion, is a point you could improve on. But first you have to stop feeling hurt so that the real information gets through to you.

The way I'm influenced by what's written has more to do with understanding the difference between what I wanted and what came out in the end. Like seeing things through other people's eyes. It helps me calibrate myself, but not in the sense that I'll write the way others want me to, but in the sense that I'll try to refine my writing so that next time, what I want to say coincides as well as possible with what is understood. For example, there is a steady stream of opinions that say that archaisms make the text more cumbersome. However, they have appeared in my books for very specific purposes, for the creation of atmosphere, for the authenticity of a dialogue that is supposed to have taken place three to four or five centuries ago, for a brief revival, because it is not very commendable that we find them difficult to understand. What we did at Chiajna, unlike Manuc's Inn and The Last Crusade, is that we made sure that no more than one archaism appeared per paragraph and that it was very clear from the context what it was about. This is how I keep track of what is written.

Your novels have also brought you awards and nominations, such as the Writers' Union Debut Prize and your placement among the finalists at the Festival du Premier Roman de Chambéry or the Book of the Year 2019 Award offered by the Brasov Branch of Writers' Union. How do these distinctions influence the life of a book and what is your dynamic with them?

An award or even a nomination makes the book more visible. The information that that title has appeared in the world reaches more potential readers. But from what I've observed so far, it's not enough just to get that novel bought. Once they find out about the book, people start looking for other readers' opinions. It's only reader discussions or reading impressions on Goodreads that lead to buying or not buying the book. For me, an award or a nomination is a confirmation and a reward for the soul. You work further differently after you get the confirmation that you are doing the right thing. I think you work more peacefully, freer from the moments of fretting.

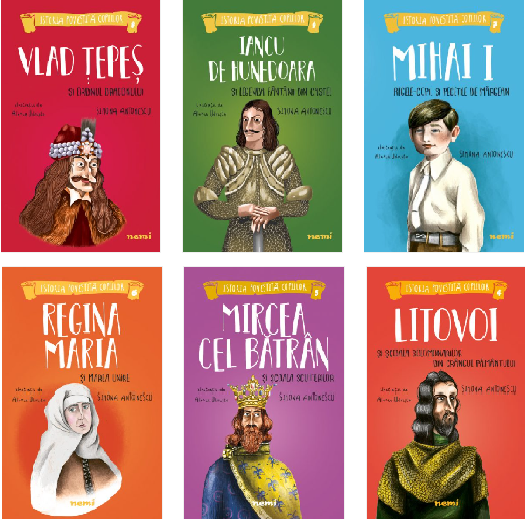

Alongside the novels published by Polirom, you also wrote History Told to Children, a series of nine volumes (illustrated by Alexia Udriște) centred on symbolic characters of Romanian history, published by Nemi, the children's imprint of Nemira Publishing House. Was the research and writing process different for these books? What about the interaction with the public after their publication?

The last volume of the series, the one about Stephen the Great, has not yet appeared.

The documentation was very different. The series is aimed at the 7-12 age group, so I had to adapt to that kind of readership. This meant fewer years, fewer exact calendar dates, more documentation of childhood games from different eras, what sweets there were or what life was like for an ordinary child, a landowner’s child or a royal offspring.

Interacting with children is the best reward for writing a book for them. I get countless questions every time, I love getting questions at any meeting with readers, and the children have no restraint, unlike adults, when the questions start, the whole room becomes a forest of raised hands. A beauty!

Little gossip moment. Returning to Chiajna, you revealed, from the moment it appeared, that (again) Laura Câlțea gave you the idea of writing such a novel, but you didn't hesitate to say that you didn't follow her suggestions closely. For curious readers, among whom I count myself, can you give some details on these "deviations"?

I remember the moment, I think you're referring to the discussions at the launch in Bucharest, at Humanitas Cișmigiu. I was referring then to another subject that Laura slipped me at one point, namely Mița Biciclista (i.e. a Romanian woman known for her extraordinary appearance and for riding the bike in the time between the two World Wars), but the character didn't appeal to me at all, "she didn't speak to me".

Which of the books you've read recently has brought you joy?

I treat my motion sickness with intense reading. Pressure differences give me big problems, something with the inner ear, it’s complicated. The fact is, the first thing that came to mind when I first felt so sick was to immerse myself in a book to forget the painful reality. My most recent trip was to France, where I had a small tour with Diana Bădica and Corina Ozon. Both flights were layovers, so on four planes I read Héritage by Miguel Bonnefoy. Absolutely delightful! The story of French emigrant families who left before WWI for Chile. It has some poignant imagery by itself, not the style in which it is written. A character leaves with the last vine cutting in his pocket and plants it in a hat, with a handful of soil also brought from his home village, when his first child is born. A very sensory book, at every turn you are engulfed in waves of colour, exotic tastes, storms of flavours, this interweaving of cultures is beautifully rendered. I travelled perfectly with Héritage, in every way.

[Photos are part of Simona Antonescu's personal archive.] [Translated into English by Oana Dragomir.]