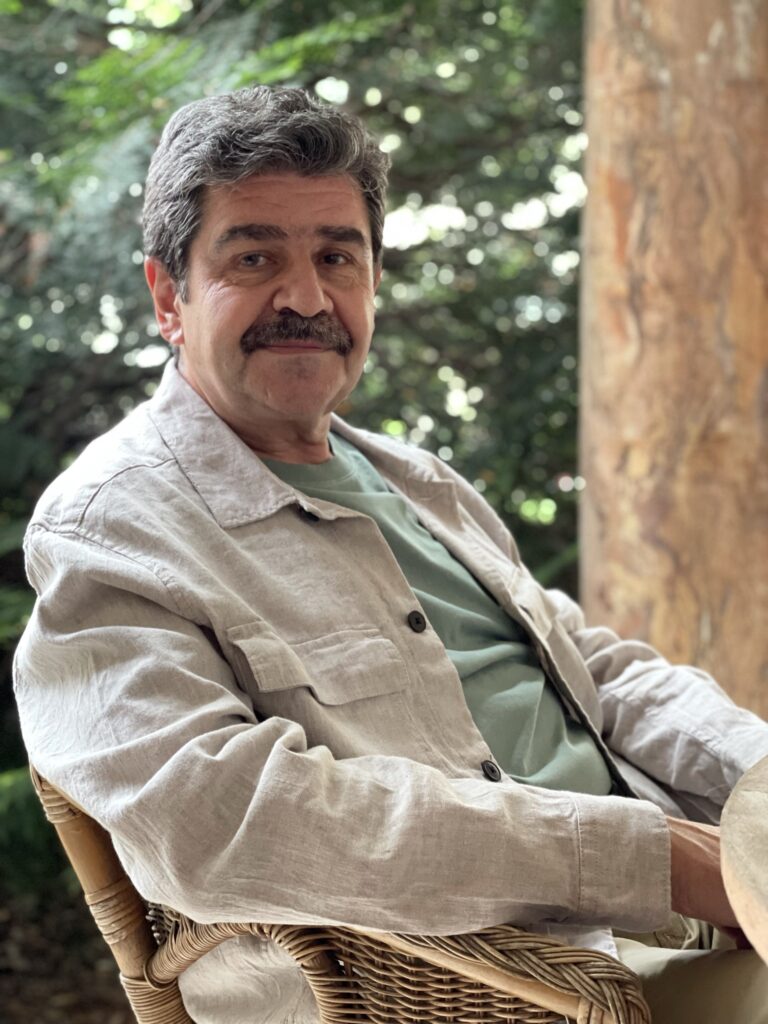

Radu Paraschivescu is a writer, translator, journalist, editor. In fact, he’s one of the most appreciated and best sold Romanian writers, a prolific translator, producer of the “Dă-te la o carte” and “Pastila de limbă” shows, broadcasted by Digi 24 TV station between 2014 and 2019. He presents and produces “Vorba vine” at Rock FM and was the coordinator of the “Râsul lumii” collection at the Humanitas Publishing House. Among his books we can find Bazar bizar [Bizarre Bazar], Ghidul nesimțitului [The Moron’s Guide], Cu inima smulsă din piept [A Heart Torn out from the Chest] (recently translated and published in Portugal), Fluturele negru [The Black Butterfly], Am fost cândva femeie de onoare și alte povestiri [I Once Was a Woman of Honour and Other Stories], Vitrina cu șarlatani [The Conmen Shop Window], Acul de aur și ochii Glorianei [The Gold Needle and Gloriana’s Eyes]. Since February 2021 he produces “Vorbitorincii” podcast alongside Cătălin Striblea.

You published your first book at Libra Publishing House, the second one at Rao, and the next ones are in Humanitas’s portfolio. How was the debut (that I know you’re not very fond of) and how did you end up to become one of the most appreciated writers of Humanitas, who has an author collection dedicated to your books?

There is another episode between the Libra-RAO moment and the Humanitas moment. Let's call it “Maşina de scris”, Domniţa Ştefănescu's publishing house, who, discreetly and delicately, published the first edition of Bazar bizar [Bizarre Bazar]. At the time of its publication, I was already at Humanitas. This episode has its importance, because the volume reached Gabriel Liiceanu through a former marketing colleague of mine. Gabriel Liiceanu read it, he seemed to like it and asked me why I hadn’t brought it to Humanitas. I assured him that because of shyness, and he assured me that I was a fool. The first book I published at Humanitas, Fanionul roşu (campioni de vis, gesturi de coşmar) [The Red Banner (dream champions, nightmare gestures)], kind of went under the radar, because I didn't really have a public outline, and the readers of Humanitas didn't really care about sport literature. The book that established me as a Humanitas author was Ghidul nesimţitului, in 2006, a book I just found out that sold 280 copies in September 2021, 15 years after its release. Ghidul is approaching a total circulation of 70,000 copies. After something like that you gain courage. The debut, with Efemeriada, the novel published at Libra in 2000, was a total fail and I can only congratulate the publishing house for opting for a small print run. The failure was strictly my fault, for I had longed for a fulminatory debut. I had written it under the logic of astonishment, which seems to me, two decades later, a boundless nonsense. A form of infantile rebelliousness from which, fortunately, I recovered quickly.

How does the process of proposing a new book take place now? Do you present the editor an idea, a proposal or a finished manuscript?

If anyone had predicted in 1995 my today relationship with Humanitas, I would have sent them quickly for a mental checkup. Now things are going like a waltz in a Viennese ballroom: harmoniously, fluidly, without stridency and procrastination. Sometimes I suggest only an idea for a new book and, after the editor’s OK, I get to work. Sometimes, more often than not, I come straight with the book and hand it over. And there are situations in which the publishing house asks me: what are you doing, what are you writing, what are you bringing us? From this it can be deduced, without the risk of error, that I write almost all the time. And when I'm not writing, I'm translating. I have been a Humanitas author for 15 years and – with no exaggeration - I still have moments when I feel like taking the reality test by pinching myself.

Most (if not all) of your books are edited by Lidia Bodea. How is the writer-editor relationship? Were there any situations in which you negotiated words or snippets of text? How do you reach the compromise that gets to the final form of the book?

I think only three of my books had other editors, namely Alice Ene, Mona Antohi and Horia Barna. Otherwise, yes, Lidia Bodea edits all my books. I thank her - less often than I should - equally for the quality of her editing and for the time she invests in my texts, given that she is one of the people who carries the publishing house on her shoulders. The relationship between me and Lidia is cordial-transparent in terms of text discussions. Her interventions are minimal, perhaps because my writing is not that bad. We review as many observations as there are and I accept most of them gladly. In fact, I don't even know if I've ever had any doubts, as long as my confidence in Lidia's eye is full. This kind of discussions doesn’t take more than ten minutes in general. Therefore, “compromise” and “negotiation” are terms too big for what we do before the book goes to printing.

You translated important writers (if we are to mention only Salman Rushdie, William Golding, Jonathan Coe, and J.K. Rowling) and talked about your first experiences as a translator and the pros and cons of translating in an interview for Suplimentul de Cultură. How did you come to collaborate with the publishing houses for which you translated (Polirom, Trei, Nemira, Humanitas Fiction) and how has the relationship with them evolved over time?

Naturally, at first, before I became known as a translator, I was the one running after publishing houses. For years now, they are the ones looking for me (it's true, without necessarily running). I had some inconveniences as a translator and I was careful to publicly denounce the unscrupulous behavior of the editor and not engage in any other collaboration with him ever again. In 1994, the owner of the publishing house I was working for stole a translation I did for a William Golding title and published it under his name. Another publisher wanted to pay me half the fee we agreed and for which he had obtained a grant, aiming to put difference of money in their pocket. Another refused brutally and repeatedly to pay me for the new editions of some books I translated (a biography of Churchill and a co-translation of Henry Kissinger). Another one, really funny, offered me a translation contract in which the spaces between words were not included in the 2000 signs on the page. I told them that in this case, I would send them a block translation, consisting of a single word spread over 400 pages, and they could separate the words, if it was that simple. Finally, another publisher (whose employee I was at the time) paid me only a third of the amount due for a football Larousse (co-authored and co-translated). You mentioned Humanitas Fiction. I collaborated with them until two years ago, when the director of the publishing house gave me a sign of non-collegiality that made me break off relations. They remained broken to this day, and they will stay like that. Besides, I refuse to have ever something to do with the publishing houses All, RAO, Univers, Elit, Orizonturi and Curtea Veche. Instead, I enjoy collaborating with Polirom, Nemira, Trei (plus Pandora M), Baroque Books & Arts, Art and Arthur. Not to mention Humanitas Clasic. In general, I work with anyone who demonstrates the seriousness and honesty that I offer. I translated 115 books and I’ve never been late, not even with a single day. Today I have the advantage of refusing what I don't like, choose my collaborations and translate from authors I’m very fond of: Jonathan Coe for Polirom, Julian Barnes for Nemira, Stephen Fry for Trei, etc. It's an advantage, of course, that my earnings don’t come from translations alone.

I assume that you receive more translating suggestions than time would allow you to do. What are the most important criteria when accepting such a collaboration?

I refuse from time to time, usually because of the time crisis I'm in. I rarely fall back on the refusal. I did it recently with Pilot Books Publishing House, led by Bogdan Ungureanu, to whom I had refused a relatively attractive financial proposal (on Romania’s level, let's be clear). Later I was sorry, Bogdan is a man and editor of quality, so after a few months I returned and put myself at his disposal, for a David Foster Wallace that will appear in 2022. I have a few acceptance criteria which are rather simple: to enjoy the author and the book, to trust the publisher and to agree on the rate. I'm not saying anything new, the excellence rates in Romania would be seen as volunteering in other countries. For example, I have full confidence in publishers such as Dan Croitoru from Polirom, Ana Lotts-Nicolau and Alexandra Rusu from Nemira, Magda Mărculescu from Trei, Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu from Pandora M, Dana Moroiu from Baroque Arts & Books, Diana Zografi and Florentina Hojbotă from Art / Arthur, just mentioned Bogdan Ungureanu from Pilot Books, plus my colleagues from Humanitas. There are people I could work with without translation contracts, just based on their word.

Because I mentioned above the relationship with the editor of your books, how have you been collaborating with the editors of the books you have translated so far? Are you reviewing their suggestions, working together on the text?

From case to case. Mona Antohi, my colleague from Humanitas and a truly exceptional editor, shows me the interventions (not many) she makes on my translations and consults with me every time. I am almost embarrassed, because, as in the case of Lidia Bodea, Mona's eye is impeccable and she sees everything she has to see. I know I only got angry twice when I found out that the editor (I won’t name them and no, they’re not from Humanitas) had turned my translated text into a synonym test site. I had written “against”, they had proposed “opposed to”; I had written “said”, they had proposed “told”; and so on. I got up from the table, greeted them, and left. Most of the time, however, I am not called to see the editor's remarks. And frankly, I don't even care. I have no fixations and stubbornness, as I hear other translators have. I just hope that the editing process helps the text and does not boycott it. I say this because I also have examples of editors who have corrupted the translated text (someone else’s, not mine). Scrupulous and sleeping with the dictionary under their heads, they did not see any licenses or intentional distortions of the original language and hurried to put it in the corset of the correct expression recommended by the reference tools. In this way, they stylistically castrated authors who were not to blame.

If you were to advise young people interested in literary translation, what would be the first three things they should do and the first three things they should not do?

I'm afraid I don't have that many recommendations. I certainly have one, even if it seems trivial: not to think that they know the source language. More precisely, that they know it to perfection, in also her recesses and niches. A surprise, an unexpected meaning, or an unexpected combination can occur at any time. Hence the recommendation: keep your dictionary close. Don't push your self-esteem to the point where you think you don't need it. I know an editor (they were also my employer at one point) who put the equal mark between using a dictionary and ignorance: “If they look in the dictionary, it means they don’t know the language.” It was impossible for me to convince him that things were completely different. I was even tempted to murmur “I know I don't know everything,” but I realized it would be useless. The man had beliefs of cement.

After the adventure of being a teacher, about which you talk in a podcast you attended, you entered the publishing industry, first as an editor at Olimp Publishing House, then at Elit and Rao, and since 2003 you have been working at Humanitas. How did you get to Olimp and how was the journey to Humanitas?

Doina Uricariu needed a psycho to translate a 600-page thriller in a month: The Holcroft Covenant by Robert Ludlum. (Doina was and remained, I suspect, the illustration of the notion of workaholic, that’s how I remember her, working her guts off and asking the same from others.) She found me at the National Library, where I was working in the spring of 1993, and she made this proposal that a person in their right minds would probably have rejected. I accepted the proposal, took unpaid leave from the library, didn't leave the house for a month, and did the translation. By hand, because my typewriter had broken down, and computers would not be a thing until many years later. Doina was impressed and offered me a job offer at Olimp. I accepted not only for the salary, but also because I could get out of the routine of working for the state. I realized in time that “at Olimp” is not the same as “in Olympus”. The publisher's accountant (and also the owner's father, it seems to me) paid the salaries when he felt like it. And he didn't feel like it too much. After nine months I went to Elit, with a splendid dive out of the frying pan and into the fire. A translation was stolen from me there, as I wrote earlier, and I was not given back certain English books that I cared about. I don't know how I resisted at Elit for a year and a half, but I remember it was the only place I left slamming the door. At RAO I got at the invitation of Ondine Dascăliţa, a woman I still regret not seeing more often and at the same time a great professional. There I found Angela Cismaş, Livia Szasz, Gherasim Ţic and others, plus Ondine, who was the editorial director. After more than seven years (too much, I realize now, the team had changed and not for the better), in February 2003, I left for Humanitas. The boss of RAO seemed shocked by the mistake of Gabriel Liiceanu to take me in his yard and he was careful to tell some of my future colleagues that they will have reasons to regret it. Fine, elegant, subtle. I'm still at Humanitas, a sign that reality has disproved the prognosis of the RAO boss, but, isn't that right?, if you can speak ill of someone, it's a shame not to. Even if you have no reason.

Do you have memories that stuck with you of your early days? I imagine that the logistics were different then, without Track Changes, without too much internet, but the writers and translators having the same big ego.

I have enough memories, not all pleasant. The first is related to my debut as a translator, missed due to a publishing house with no minimum requirements in the field. Although I am an English translator, my first one was a translation from French: Les Anges noirs by François Mauriac. The book itself was outrageous: no editing, no proofreading, no pagination, nothing. Plus an ambiguous cover, meant to suggest acrobatics from Ninja movies (probably the graphic designer hadn't gone through the text, hadn't heard of Mauriac and was guided by the TV guide that had enough martial arts movies and nervous citizens at the time). I still remember that the editor who stole my Golding translation didn't let me write the text for the fourth cover and did it with his own hand. That's how the readers found out that Golding was born in Born St. Columbus Minar and died at Died Tullimaar. The distinguished gentleman had taken over from Who’s Who, taking care to tell me that I did not know English. Finally, let me not forget to mention a personal goof. Inadvertently, but that's not an excuse. While working on The Deceiver by Frederick Forsyth (Dezinformatorul, Univers Publishing House), I translated the bonnet of the car to “boneta mașinii”, although I knew very well that bonnet means “hood”. The bottom line is that the editor didn't even see the goof, and that's how the book was published.

Have you come across unflinching writers or translators?

I have had such encounters, although in a profession like ours, unflinchingness betrays psychoanalytic flaws. I have dealt with excellent, acceptable, mediocre and catastrophic translators. It is true that some of the latter were tufted and ready to walk to the end of the world, for it seemed shameful to admit an error. One such lady wanted to convince me that “Turin” in English is a small town in Switzerland or Belgium, although in the text it was “The Shroud of Turin”. She would have been willing to remake the map of the world instead of admitting her mistake. Another lady translated “chick-lit” by “lumina puilor” by logical-philological connections a little harder to trace. A gentleman mind-blowingly translated “Tate Gallery” into “galeriile lui Tata”, and then handed me two more gems: “Ţi-a plăcut? întrebă ea, balansându-se meditativă în carici” (from a Harold Robbins novel published at Olimp), and a translation of a guide of London published at RAO in which only past tense simple was used (which I had to turn into past perfect from beginning to the end): “romanii veniră”, “ciuma se sfârşi”, “războinicii se bătură” etc. Not to mention the translations that are easier to start from scratch than edit. Unfortunately, I also had writers with problems. Three examples: a) a colonel (I think) who tried to teach me to edit a book about the Palace of the Parliament and who threatened to take his book to another publishing house (a pity he didn't do it, it would have spared Humanitas from some loses); b) an otherwise very good actor, tickled by the ambition of the memorialist self-portrait and rarely able to write a sentence without mistakes and grammar mistakes; c) an otherwise trained man, who threw a book of almost 600 pages on my table, not wanting to take a syllable out of the text, but instead pissing me off for months with phone calls, e-mails, suggestions and marketing plans that were not his business. When I was at RAO in 2000, I think, I had the displeasure of talking to a citizen caught between metaphysics and catharsis (the mean persons read “clitoris”), who had come to propose his wife's stories to publication. They were texts of a vague nationalism, in which the scream of lambs could be heard, and all the clichés were in place. I thought it was not worth publishing, I said my opinion, and the citizen stared at me and said harshly, “You're from that Patapievici’s group, right? Do you know what I would do to you? I'd shoot you in the gutter.” I wanted to call it Bad habits die hard, but I suspected that sinking into catharsis had stopped him from studying English.

You coordinated „Râsul lumii”, a collection of funny books, in which you included authors skilled in the practice of seduction through words, as it is described. What does this job of “book hunter” entail, as Gabriel Liiceanu calls it in Povestea insulei Humanitas [The Story of Humanitas Island]? What are its challenges and satisfactions?

I think tenderly of “Râsul lumii” and I deeply regret its exit of the market. Maybe it was my fault, maybe the idea of bringing together only funny authors was a ghettoization that prompted the audience to be circumspect. Some readers may have been unfairly judging that if a book is funny, it lacks literary value, which is terribly false. I’ll mention only a few authors: Woody Allen, Păstorel Teodoreanu, Eduardo Mendoza, Peter Mayle, Andrei Pleşu, Tibor Fischer, Tim Lott, Christopher Buckley, Nigel Williams. The years when I coordinated “Râsul lumii” made me realize that a “book hunter” had to “hunt” daily and not postpone the expedition except for serious reasons: illness or death in the family. Being busy doesn't justify procrastination. Constant reading - of books, catalogues and reviews - is a must and works for one of the publisher's first qualities: the flair, a “nose” capable of sniffing double success: value (awards, etc.) and sales. Publishers without flair have little chance of staying in the market if there isn't a protector behind their business who is willing to pump up and lose money. Satisfaction of the “shot down” target during the hunt is sometimes platonic: You're the one who discovered X or imposed Y. At other times, satisfaction is found in large print runs and pre-orders that herald market success (Humanitas has the non-Nobel Prize-winning Paulo Coelho and Elizabeth Gilbert cases, but they attract sales that can shape an editorial program which also contains formidable writers, but maybe less appreciated by the big public). The Nobel roulette, in turn, has frustrations and joys, depending if you managed to guess the recipient of the prize in time to buy the rights. As far as I am concerned, I have had modest and unrecognized satisfaction in this regard: I once contributed, through recommendations and insistence, to bring David Lodge and Julian Barnes on the Romanian market. No big deal.

You are familiar with the books of exported and exportable writers. What are the most important features of a book from a publisher's point of view, to catch his or her eye and decide to translate it?

To a large extent, these traits attract not only the publisher, but also the reader for whom reading is a hobby, not a profession. From my point of view, in order to be tempting, a book must first of all tell a story that “holds” and “holds you ”, whether it is a novel, a book of short stories or a memoir. Secondly, such a book should arouse in the mind of the reader, especially the knowledgeable one, an enviable expression in the statement “such a thing I would have liked to write myself”. Publishers - not all of them, but many - would add that a book of interest should already have some potentially important prizes. Here I would put a flat key. I know award-winning books both in Romania and abroad that could have been better written. As I know big names who have written small books and small names who have written big books so far. Fame is not always a guarantee.

From this point of view, was your writing influenced by your activity at the publishing house? Did you write your books (the fiction ones) thinking of potential foreign readers too?

Never. It happened to me that, after finishing the book, I thought it would be a good translation material, yes. Especially with regard to novels whose action takes place in Italy, Ireland or Portugal of past times. But it never crossed my mind to adopt useful captatio strategies in front of the presumed Finnish, Turkish or Spanish reader. If the problem arises to reach the public in other countries, the task of making me as seductive as in Romanian will fall in the hands of the translator. That doesn't stop me from dreaming, especially on soft autumn days. To imagine that my novels will be turned into movies. And to push the delirium and the dream to the point of choosing the cast alone - not the director too, who will incarnate only who knows how. In the days when the imaginary fields I walk on seem endless, I dream of a poster with James McAvoy, Léa Seydoux, Robert Downey Jr and Helen Mirren coexisting. Monica Bellucci, no. The pedestal I put her on is so high that I can't even look up to the hem of her evening dress.

Cu inima smulsă din piept [A Heart Torn out from the Chest], your 2008 novel, was translated by Corneliu Popa and recently published in Portugal by Guerra & Paz. The translation was made with the support of Romanian Cultural Institute's program to support the export of Romanian literature, but how did the book come to the attention of the translator and the publisher and what is its Portuguese path after publication?

The translation of the novel about Inès de Castro and King Pedro of Portugal is a first for me. Nothing of mine had been translated before, so the news I received from RCI Lisbon and Guerra & Paz made me shudder with pleasure. Manuel Fonseca, the editor of Guerra & Paz, was a kind host and a warm man who deserved a bow. The RCI (Lisbon + the Bucharest Filial) people deserve something similar, if not more, because they supported the translation and publication financially. Therefore, I would also like to thank the director of RCI Lisbon, Daniel Nicolescu, who is also a formidable translator (and a graphic designer with a good “claw”, if you didn't know). Equal thanks go to Corneliu Popa, a translator as diligent as he is talented. And I can't end the Oscar moment without mentioning Rui Zink, who sent a footage for my launch in Lisbon. Rui is a man who has always encouraged me and I am convinced that his lobby for me was important, maybe decisive. We rarely talk, we usually see each other at events that take place either in Bucharest or in Lisbon, but if I were to name a friend I have now among writers outside Romania, he would certainly be the one. What will happen next with Cu inima smulsă din piept [A Heart Torn out from the Chest] I do not know. But if the Portuguese want to make a movie, I'm all ears.

Did you work closely with the translator?

As close as he thought fit. Corneliu Popa is a rigorous man, who goes beyond the translated text. So he pointed out one or two detailed historical inaccuracies to me and asked if he could correct them. I thanked him, of course. There were no dilemmas regarding the translation. Being Romanian, the text did not cause him any problems, as it could have cause to an Italian or Danish translator from Romanian into his language. But I have to somehow atone for Cornelius for the torments I was subjected to on another occasion: when I wrote a text for the bilingual album Azul de Lisboa / Azur de Lisabona, which I coordinated for the same Guerra & Paz publishing house. I then went down the aisle of puns and other witty tongue twisters, not thinking that some might be untranslatable into Portuguese. Sources who did not want to remain anonymous (but who I won’t divulge here anyway) informed me that poor Corneliu had taken his katana out of the closet and meticulously sharpened it. Not for seppuku, but for the meeting with me. I brought him his favorite Romanian chocolate, but I still don't know if I can consider myself rehabilitated in his eyes.

How was your relationship with the Portuguese publishing house? Did you negotiate the print run, the cover, the marketing campaigns?

It's simple here: the answer is “no” on a straight line. I had the shyness of the one being translated for the first time and left everything in the hands of the publishing house. I signed a contract, received an advance, the print run was established (well below my print runs in Romania) and I participated at the launch in Lisbon, in the first half of July. Guerra & Paz complied with the contract to the letter. And I start from the idea that the people there have an interest in not keeping my novel in storage and they will try to place it as good as possible. It exists in a number of important bookstores in Lisbon, and Corneliu reported it to me in a bookstore in Porto where he entered relatively recently. Corneliu – it would’ve been a pity not to mention - also made the cover proposal, which the publishing house accepted immediately. I’m also glad about it, it’s a great cover.

Perhaps more than ever, the work of a writer now does not end when they send the manuscript to the publisher, but continues, getting involved in promoting their own books. You participate actively in the life of post-published books, especially in traditional forms of promotion (launches, autograph sessions, interviews). But what is your relationship with the new media, with social media, more precisely, in terms of promotion and the relationship with readers?

For me, social media means Facebook, nothing else. Sometimes that seems like a lot to me, I admit. But I use my Facebook account as much as possible to announce my books and translations, to preview small excerpts, to keep my followers connected to what I do in the field of literature. And I'm glad that many of my over 57,000 followers are people who enjoy reading and are looking forward to my books. I have a lot of friends on Facebook with whom I communicate on the subject of my books (too). They live nearby, or in Canada, Italy or Cluj, Brașov or America. Many of these friends are not only virtual, but in the flesh, bones and books, being in their turn writers: Ioana Nicolaie and Mircea Cărtărescu, Radu Vancu and Mircea Mihăieş, Dan Alexe and Robert Şerban, Dan-Liviu Boeriu and Viorel Marineasa, Ioana Pârvulescu and Adrian Alui Gheorghe, Tatiana Niculescu and Cătălin Pavel, Petronela Rotar and Ana Barton, Ciprian Măceşaru and Lavinia Bălulescu, plus many others.

Having a varied public activity, which involves several fields and several broadcast channels, you have, I imagine, an eclectic audience. Do you enjoy interacting with your readers, viewers, or listeners? How do you negotiate the “muchness” when it's too much?

Sometimes it seems to me that the “muchness” does not exist, other times, on the contrary, I have the impression that it is pressing on my neck. And that's probably natural, given the many unforeseen events of the day. I keep in touch with the public in as many ways as I can find, especially in these upside-down times. I've done a few small contests on my Facebook account, rewarding the winners with books written or translated by me and just published. I left some of the prizes at one of the Humanitas bookstores, met others in person, and talked for a while. I do it simply because I like it, not for strategic reasons. The only constraint here is time, as I said. I enter very often (too often, some friends reproach to me) in dialogue with those who comment on my posts, regardless of the subject. And I meet viewers and listeners frequently and casually, without ever avoiding them. It's rewarding to be stopped on the street or on the subway and shake hands. I enjoy it. There is no point in being hypocritical and saying that I am not interested in the public. I'm really interested in the public’s feedback.

In the short bio note on Humanitas website, you mention the pleasure of listening to David Gilmour. Does that exclude Roger Waters? If Gilmour’s 2016 Pompeii concert and Waters’ Us + Them tour would be remade, which you would hurry to?

In the presentation you mention, I also mention the pleasure of listening to Mark Knopfler, whom I had the pleasure of seeing in concert in Amsterdam and Nîmes. By the way, I also wrote a story, “Fuga mea cu Mark” [My Run with Mark], which I included in the volume Am fost cândva femeie de onoare and in which I turned him into a character. Going back to the former Pink Floyd members, entre les deux mon coeur ne balance pas: I choose David Gilmour at any time. He has a voice that quickly reconciles me to everything that is murky and ugly around me. On my bucket list, a David Gilmour concert is next door to a trip to Buenos Aires, my curiosity outside of Europe. On the other hand, I went to Roger Waters' concert in the Constitution Square in 2014 and it seemed like a high level show. Some comparators with groupie skills told me that it was a concert over those in Budapest, Prague and Thessaloniki. I have reasons to believe them. Just as I have reason to be saddened by Waters' latest ideological concessions, even if I admit that When the Tigers Broke Free is a song that sticks me to the wall every time I listen to it. [Translated into English by Silvia Codescu.]