Iulia Nani is a marketing, communication and personal branding specialist, as well as a translator and a writer. She’s been the Communication Manager at HR Club, a well-known Romanian HR agency, for some time and has been translating for Publica Publishing House for ten years. She’s also a published author for almost a year, her first novel being issued by Bookzone. Iulia easily navigates through business, economics and personal development books, is fluent in multinational corporation, and seems to know exactly what brings joy and saddens to the corporate people, whose lives she inspired from in the making of Victoria, the corporate superheroine. And because she discovered the secret of having longer days, she always finds time for family, a cat, and a bit of piano.

You are a communication manager, but you also have close connections with the book market. What’s the perspective of a specialist when it comes to the communication and marketing dynamics on the Romanian book market? Did you notice any changes compared to 10 years ago, let’s say?

I’ve come to understand the communication and marketing dynamics on the book market only this year when I published my own novel, Cine nu e gata (Ready or not). Until then, as a translator, I wasn’t involved in the advertising component, much less for the Romanian volumes. I knew there were book fairs, launches, blog reviews, and so on, but that's about it.

At the moment, I think social networks have the power, as Instagram posts and Facebook discussions, for example, weigh much more than the publishing houses’ official marketing messages (which, incidentally, applies to almost all brands and industries). We’re living in an era when the brand exists in the eyes of the consumer – everyone perceives it through their own lenses, and the discussions and people’s recommendations can’t be controlled or influenced to a certain extent.

And speaking of brand, I believe Romanian authors have a rather “shabby” one – I know some publishing houses decline them from the beginning with the message “We don’t publish Romanian authors (anymore)”, without even reading the manuscript; I’ve seen people declaring on Facebook that they don’t read Romanian contemporary authors “because they all write about communism” (?!); I’ve seen publishing houses promoting foreign authors more enthusiastically than the Romanian authors they have in their portfolio. And there’s also the fact that, generally speaking, Romanians don’t read that much.

You translated a lot of books for Publica. How did you become a translator and how did you get in touch with Publica?

It happened in the year of grace 2011. I was already a fan of Publica books, they had many topics I was interested in (branding, behavioural economics, etc.). Besides, I wanted to change my career and try something new. One day I thought that I’d like to translate for them, so I’ve searched online the name of the CEO, found his email address and sent him a message, asking him to give me a chance, since I had an advantage: I was a Foreign Languages graduate, I had been working for about ten years in marketing, so I had a richer and more practical perspective on what business meant, which would have a positive outcome on the translation’s quality.

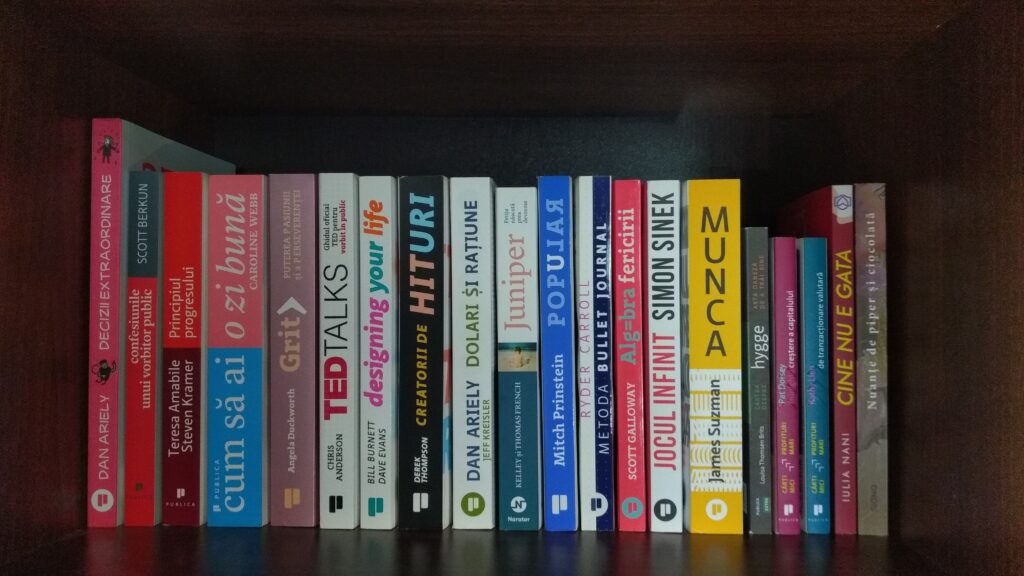

Luckily, he received my email, and was very open; as a test, he sent me a few pages to translate and towards the end of 2011 I signed my first contract for the translation of Confessions of a Public Speaker by Scott Berkun. And here I am, 10 years and 18 books later! I’m very thankful!

You also translated more “specialized” books, but also titles from lifestyle (Hygge) and a Narrator book, Juniper. Are there differences between translating some and others?

I don’t have different approaches… I take everything as it is, trying to follow the author’s overall style (more office talk here, more informal there, etc.) and the book’s spirit, that’s all. I don’t find the borderlines between styles so well defined. In Juniper, which is in fact a real story, there were enough medical and specialized terms, which required research. In business books, the authors are increasingly embracing storytelling, narrating events, recounting conversations, some colloquial, so certain passages sound like they’re part of a novel.

Many (if not all) of the social sciences and personal development books in English have a certain jargon that was kept as such in spoken Romanian. How do you proceed when translating? Do you leave the original terms or look for the Romanian equivalent?

I try my best to find the Romanian equivalent, but that doesn’t always reflect 100% the meaning from the English version. For example, every translator in the field of social sciences has encountered the famous “bias” and “insight”. Biashas “prejudice” as the closest translation, but what do you do when the author uses the term prejudice for “prejudice” and considers it something different from the word bias?

In such cases, I think you have to take into account if that term is already being used in Romanian as such and then, use it as it is. In the corporate environment, in departments such as marketing, sales, and human resources, people talk Romglish anyway. There were also cases when I proposed a Romanian equivalent, but the editor decided to use the original term. In conclusion, I try not to be lazy and, unless I find a satisfactory equivalent, I leave the original term as a last resort.

Which of the translated books gave you the biggest headaches and how did you find the solution?

There were two! The Little Book of Currency Trading by Kathy Lien made me cry because there were so many specialized terms from the stock exchange and foreign exchange market, terms which were sometimes difficult for me to equivalate, for the reasons I’ve previously discussed – financial Romanian experts kept them as such and when researching on the Romanian trading sites, I was welcomed by the most trueborn Romglish.

From all the books I’ve translated so far, muuuch more pleasant headaches gave me my favourite book, Hit Makers by Derek Thompson. It had it all, from examples of political speech with alliterations to rap lyrics. A fun and fantastic challenge for any translator… I guess.

Once translated, a book passes through the hands of a copy-editor and a proof-reader. How do you interact with them? Do you agree with the suggestions, do you negotiate with the copy-editor on the text?

I receive an editing report and my translation containing the suggested changes and corrections, I browse through them and if I don’t agree with something, I simply write it in the comments. Usually, there are small things, nuances, puns or cultural references we understand differently, or maybe the copy-editor rephrases some parts because they simply sound better; sometimes they can find more inspired versions than mine. There’s no competition between us, I really want to highlight this: the common goal is to find the best version for readers.

How and when did you make the transition from translator to writer?

I’ve always enjoyed writing; in secondary school, I was always looking forward to Romanian classes, especially when we had to write something. I’ve been writing my whole life: blogs, specialized articles, ads, posts, newsletters, press releases. But 2020 was a big year for me, despite the pandemic, because I officially made it to the fiction authors’ camp.

First, I participated in a storytelling contest organized by Siono Publishing House. I sent them a story I had written with a pen in an old notebook, just in the last millennium (1999!). It was selected and displayed in the collective volume Shades of Pepper and Chocolate, in the fall of 2020. At the same time, I had finished writing my first “real” book Cine nu e gata (Ready or not)and full of hope, I was sending it out to publishing houses. About the same time I won the Siono contest, I also received Bookzone’s acceptance for Ready or not, which was released in February 2021. I don’t know how it happened, somehow the stars aligned as they say, but out of the blue, I saw my name on two books. To be honest, I still can’t acknowledge that the syntagm “author Iulia Nani” is about myself.

How did you manage to publish your book at Bookzone Publishing House?

I went through the process that any novice author fears the most, of endlessly sending the manuscript to all publishing houses and being rejected. Long story short, months of searching publishers’ contact details and sending emails went by, until one day when I got the acceptance message from Bookzone. I want to thank again the editor who read my manuscript and submitted it for publication and, of course, the management team that took the risk of publishing a debutant author, with a chick lit, a style less approached in Romania.

Were you involved in the next steps, until the publication? Creating the cover, choosing the type of paper, setting the print run?

I only got involved in creating the cover, in the sense that I told them my vision of a blonde girl and definitely a cat, and the graphic designer did a really great job, picturing Victoria as a kind of corporate superheroine, putting on her cape, ready to save her clients from a life of procrastination and whining. I wasn’t involved in any other technical details (paper, print run), but I’m very happy with the final result.

How has your professional experience helped you in promoting your own book? And from your point of view, how important is the author’s cooperation with the publishing house in this process?

I’d say that my marketing experience has been more than welcomed and, generally, it’s a strength for any author. From the fact that you know to write an elevator pitch for your book to persuade an influencer to read it, to the ability to master Facebook Ads or create illustrations in Canva, all of this helps you gain control over communication and make your own promotional campaigns, on the channels and with the messages you find the most suitable.

In the absence of professional promotion machinery, as in the U.S. where entire teams work together to help authors and “push” them into the spotlight, in Romania you’re all by yourself: you have to take the time to post on social media, send emails requesting reviews, ask acquaintances and strangers to give you stars on Goodreads, and also have a budget for couriers, ads, etc. And most importantly, you have to believe in yourself and your book, otherwise, you won’t have the energy for the things I mentioned above.

What are the greatest satisfactions offered by working as a translator? What about when you became a writer yourself?

The work of a translator gives you the joy and pride of knowing that you contributed to the spread of some new and useful ideas to those readers that don’t know the language in which those books were written. Obviously, it’s a big responsibility – not to be a traduttore, traditore. If you’re lucky enough to translate books that fit your interests, translating them is also a thorough read for you – I read a book two or three times during translation and revision and I really learn something from that! This is the advantage of translating specialized books. I don’t know if reading a novel two or three times would be as pleasurable.

As a writer, my main satisfaction is that I made a few hundred corporate people laugh and recognize themselves in the situations and characters that I depicted – a common reaction is “It’s as if I wrote this” or “Are you sure you didn’t work in the X company, you don’t know my boss?”. I think that there aren’t enough feminine voices that bring humour, irony and sarcasm in their books in Romania, and I want to make people laugh, while drawing their attention to some serious issues, such as burnout or running away from responsibility. At the end of the day, if you don’t willingly make the necessary changes in your life, there might show up a person like Victoria and make you do them... by force!

One of the books in the portfolio of the literary agency I work, is called Work Won’t Love You Back, a title which seems very defining nowadays. You have also translated two books on working at Publica, Work by James Suzman and Just Work by Kim Scott. You have a job, you translate, write, train, and the list goes on. When do you pause the work and what’s the perfect escape when you do that?

That’s true, I have a full-time job where I work on many interesting projects, I have a husband, a child, a cat, and a book I have to promote. I try to keep myself organised, not to waste so much time on Facebook, and plan everything as efficiently as possible – ever since I translated The Bullet Journal Method , I’ve been a big fan of lists.

Obviously, I work more than eight hours a day to take care of translations, I work a few hours on weekends as well, but I have some strict work-related rules in order to avoid burnout; for instance, I stop myself from working in the evening after a certain hour, so I can spend more time with my family, and I don’t let any day pass without practising the piano (I started taking lessons at the end of last year). Playing with my cat, walking in the park, watching TV-series and, of course, reading are some of my “escapes”. Oh, and I usually write short pamphlets or observations from everyday life on Facebook, just to exercise my writing hand. I don’t consider this work though.

In another interview, you were saying that behind a personal branding specialist there are many years of study and hundreds of books read. Which are the books that helped you the most in your career? Which books you enjoyed the most, if these two categories don’t overlap perfectly?

The most helpful books were the behavioural economics ones, about how we think and make decisions, for example, all Dan Ariely’s books. Other essential books are Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman and Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. And Malcolm Gladwell’s books have showed me what a documented writing really meant, and how attractive and captivating it is. Last but not least, Hit Makers, which I mentioned earlier, I think it’s a must-read for anyone working in promotion and communication.

Photo copyright: Dragoş Constantin/ Venus Five. [Translated into English by Cosmina Mavrodin, copy-edited by Ana Maria Mihai.]