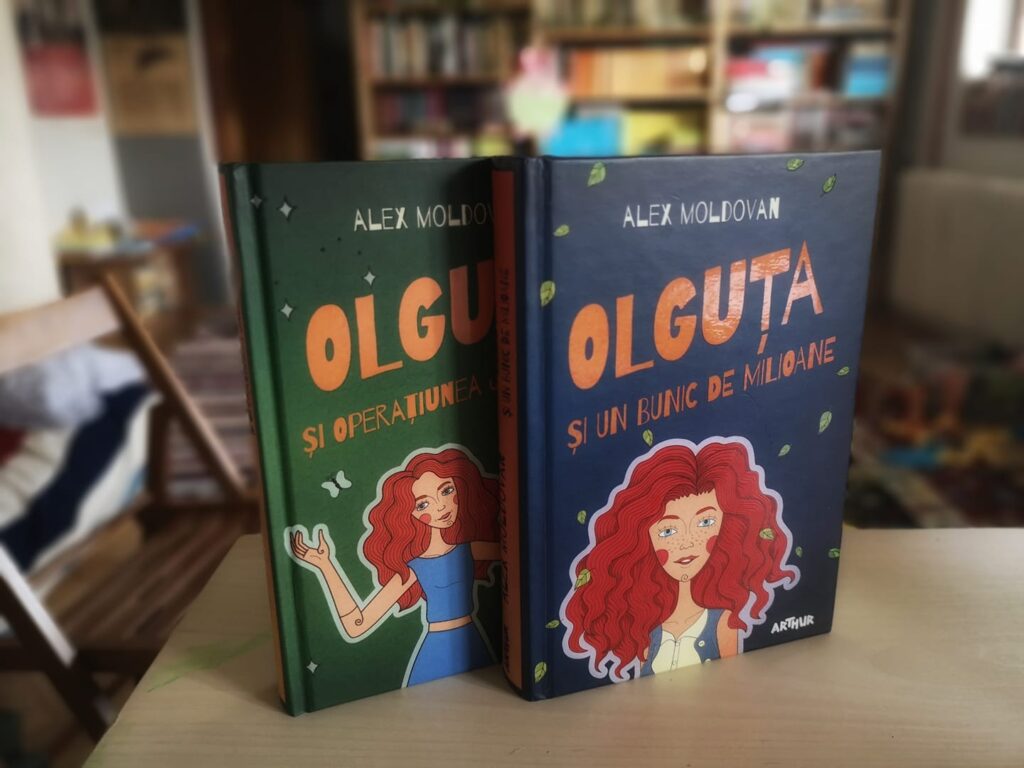

Alex Moldova is a writer of children’s literature and a translator. He published Olguța și un bunic de milioane / Olguța and the Million Dollar Grandpa,, Olguța și Operațiunea Jaguarul / Olguța and the Jaguar Mission and Băiețelul care se putea mușca de nas / The Boy Who Could Bite His Nose,all at Arthur Publishing House. He has a blog, he organizes jazz festivals and creates some of the best Facebook statuses. Among others.

In an interview from a couple of years ago Lavinia Braniște said that, for a better functioning of the book industry, she would “befriend everybody with everybody” so she could cultivate the dialogue. Do you think everybody can be friends with everybody in this field? Would you befriend everybody?

I don’t think I could and I wouldn’t even want to do that. People are too different in the editorial world for me to wish to be friends with all of them. I don’t want to be friends with everybody in general too, I try to pick to the best of my abilities my friends and acquaintances, but a thing like that can be useful; to know as many people as possible and maintain at least amiable relationships, if not friendships. In times gone by you’d ask them out for a coffee or something, that’s not possible now and you send them a text or initiate a discussion of Facebook or somewhere else eventually. I think it’s very important to be known one way or another, as a translator and as an author, to have a certain visibility among potential collaborators. As the years I’ve been working as a translator went by I realized this thing is important and that as you gain visibility, you receive more offers. It’s not that relevant as an author, at least not in my case, because I write literature for children. Therefore a pretty clear defined zone. But it helped me very much as a translator.

Who’s an author’s best friend?What about a translator’s?

An author’s and a translator’s best friend is the autocorrect in Word. But it’s really good to get along with the people from the publishing house, with the people you’re working with, because, the same way they depend on you, you depend on them to a certain extent. And I try to initiate conversations even if we don’t talk for long periods of time during which nothing interesting for me or for them happens, I reach them sometimes, especially because I got to know some of them more personally, at book fairs, through all kinds of situations more or less official, and they’re nice people. I try to be as open as possible and to keep in touch with them.

Does it matter in the current editorial world the groups of friends or acquaintances you find yourself in? What about the city you live in?

Yes, it does, because in this editorial world there are more powerful and less powerful groups of people too, smaller and bigger publishing houses, more relevant from this point of view. The physical closeness matters too, because you talk in one way on the phone and through texts, and in other way when you meet people face to face. And if you’re from a big city, such as Bucharest, because that’s what we’re talking about, there are concentrated the majority of important publishing houses, it helps to get out for a beer, maybe an ice cream, to meet with each other. You randomly bump into people too, thing which doesn’t happen if you live in a small town. Not even in a medium one, like Cluj is. There is editorial activity in Cluj too, but not in the area I’m interested in. I’ve worked with one or two publishing houses from Cluj, but a really long time ago. The publishing houses I’m collaborating with are from Bucharest, they have their headquarters there, they work there and I realized that the fact that in the last years I got to the book fairs, to those huge things, with tens of thousands of people, where I met the ones I had talked on the phone with, mattered. And that thing helped me, to see all of those whose names I knew only from emails, texts, letters, and contracts envelopes. And at a book fair you have the chance to meet everybody, because, usually, publishing houses bring their people there. And you can find there everybody, from the driver of the publishing house to the director. And I find that to be a “democratization”. Not a democratization per se, but it’s cool that you can find all those people in one place.

And at the book fairs from abroad, such as the one from Bologna?

I didn’t get there, unfortunately. I should have last year, but we all know what happened next.

You were saying in an interview that you started writing Olguța și un bunic de milioane / Olguța and the Million Dollar Grandpa, when you found out about the Arthur Trophy. You had the book project in your mind or was the manuscript contest the trigger?

A fost un moment ciudat. În perioada în care editura Arthur a inițiat Trofeul Arthur existau slabe șanse sau erau șanse aproape de zero să fii publicat ca autor român de literatură pentru copii. Se încercase la un moment dat marea cu degetul, dar existau foarte puțini autori de cărți pentru copii din România. Piața consta 95% din traduceri. Și nu aveai unde publica. Când am descoperit concursul, nu am avut nevoie de mult timp ca să încep să scriu. În momentul în care mi-a venit ideea că aș putea participa și publica, m-am pus la calculator și am început să scriu, nu m-am gândit foarte mult, fiindcă m-am temut să nu-mi fugă ideile, să nu le pierd, și lucrurile s-au desfășurat cumva de la sine. După aia mi-am dat seama că, în anumite părți, primul volum pare scris așa, după o rețetă. Dar nu e scris după o rețetă, pentru că eram la prima carte și nu citisem încă foarte, foarte multe cărți de literatură pentru copii contemporană. Și s-a desfășurat destul de instinctiv, așa, și cu multe poticneli. Mă gândeam la un moment dat că primul volum l-am scris în aproximativ doi ani. Pare foarte mult, mai ales când mă întâlnesc cu copiii și le spun chestia asta. Pentru ei doi ani e imens, o mică eternitate. Dar aveam și jobul de traducător, și ce mai aveam cu familia, diferite chestii, așa că aveam destul de puțin timp să scriu. Volumul doi l-am scris cam într-un an, iar volumul trei cam în șase-șapte luni. Deci se poate învăța din greșeli, ca un fel de semiprofesionalizare. Nu știam I didn’t know what I should do, but I knew what shouldn’t do, where I shouldn’t go. we for many other writers that was a click, the fact that there’s the possibility of publishing at a pretty important and serious publishing house. The publishing house that publishes Harry Potter.

You’ve been publishing only at Arthur since then, both stand alone and collective volumes. Have publishing houses proposed you to publish elsewhere too?

I received some proposals, but it didn’t feel right to switch. As I said, it’s a big publishing house, and this kind of stability matters. And that can be noticed too, in printings. You have many other advantages too.

What’s the foundation of a good relationship between a writer and a publishing house? What expectations do you have as a translator or as a writer from a publishing house?

I think each side has some expectations that are usually bigger than the reality. I think seriousness is the main argument in both cases. If I promise, as a translator, to deliver a translation by a certain date, I must do so. If I say I will write a volume for Olguța by a certain time of the year, to do so. I expect the same things from them: keeping with the terms of publication, payments, these technical matters, such as illustrations. And that’s a pretty problematic domain. The same way there weren’t too many writers of children’s books, there aren’t many illustrators either. I mean illustrators do exist, but not with the necessary training focused on books for children. Because this is a pretty special domain and it has some very well defined rules, and if you didn’t study those things and it wasn’t a matter of interest for you, it’s very easy to fall in certain traps.

Such as?

Each book requires a certain type of illustration. There are certain written rules regarding the size of the illustrations, all these technical details. I don’t know them in detail either. I see sometimes that there is an obvious discrepancy between the text and the illustrations and some visible mismatches. For me it matters even the font that was used. That can help or disturb me. There are books that I don’t like picking up or flip through because they don’t have an okay font. Here I’m referring to picture booksin particular, where every aesthetic detail is ten times more important, because that’s what it’s based on, image. As there are no schools teaching the art of picture books, it’s easy to mess things up.

Or to make them for parents and not for children?

Yes, this is an obsession of mine, with the authors that write rather to please parents and educators. And they forget that the ones who should benefit from them are children. I tried to do that in every book I wrote, both in the Olguța series and in the Băiețelul care se putea mușca de nas / The Boy Who Could Bite His Nose,, a book that actually tries to offer a small to big experience, starting from the character who is a boy to adults, and not the other way around. And that can be seen in the way a book is picked up. There are an awful number of books for children that divulge from the very first page that they were written to feed the adults’ ego and to assure them a mental stability maybe, not to drive them away too far from their comfort zone. I spend pretty much time on the few Facebook groups dedicated to Romanian children’s books and I’m often horrified when I see there some comments and some things that I find unimaginable. This child part is often excluded from the equation. It’s avoided. It’s a game of egos, adults playing people that buy books. It’s funny to a certain extent, but from a certain point is problematic, so to say, and all sorts of ideas come to your mind when you bump into exaggeration of this sort.

You’ve participated to numerous meetings with young readers, you even said not only once that’s one of the greatest parts of being a writer. Who organizes the meetings? The publishing house? Or other institutions?

Until a certain point there were a series of meetings organized by the publishing house, before the pandemic. And there were some really cool things who were supposed to take place last year, but they didn’t. I had some tours throughout the country a couple of years ago that were organized by the publishing house: I was going through schools to meet children that had or hadn’t read the book. We were talking about my books, but about books in general too. Because this topic is inexhaustible, you don’t necessarily have to talk about a certain book. And it was really cool, nothing compares to this physical closeness when you see the readers and you can get close to them without a mask on, which is something that gives me cold sweats now – I could be close to people without a mask on. But in the last year and a half we moved, obviously, online, like everybody else, most of the times on Zoom, and a very okay thing began to happen (from an angle is okay, from another is awful), in the sense that there wasn’t an institutional setting for these meetings, the teachers just came with the initiative of finding me on Facebook, asking for a phone number from a mutual friend and suggesting me meetings. It would had been great if this kind of things were organized by The Ministry, I have no idea, though if the Ministry had been involved, all the imaginable disasters would’ve taken place for sure. Or maybe not all of them, almost all of them. But teachers are looking for me just like that, so it comes from the level of teachers’. And lately I had tens of meetings; I even had weeks when I would have meetings with the readers daily. I like it very much; it's really nice to meet readers weekly as a writer. Especially because they’re children, and the little ones are really cute too, they’re enjoying it more spontaneously. And I was lucky enough to them liking my books and the reactions were good, it gives you the urge to live better. I’m usually exhausted after these meetings, because it’s pretty hard to be present nonstop, to be smart, witty,to answer tens of questions which do often repeat and so on; but I usually get out of these meetings with a smile on my face. And I like them very much.

What’s the craziest question you’ve ever been asked in your meetings with the readers? I have seen you publish some on Facebook.

try many times to write a phrase that stuck with me, to remember it even better, not only in my mind, but on Facebook too. I think the most upfront one, not crazy, was at a face to face meeting, when a couple of students asked me (I have a scar on my neck) “what happened to your neck, did you cut yourself?”. And a child got closer to me and started studying me as if I were an exhibit.

And did you come up with something?

No, I told the truth. I didn’t have to come up with anything; the truth was more sinister than anything else. It was an accident with a bottle that that cut my jugular. But I liked others too. Children have a very good memory and I usually encounter them right after they read the book and they remember a lot more details about my books than I do. They ask me some things that I simply forgot. I wrote that book 5 or 6 years ago. And look, a cute thing, I think this year a boy asked me why in the first two volumes of Olguța I put the same chapter title. There are two chapters with the same title. And I realized that was a slip on my behalf. I hadn’t thought of naming a chapter in each volume with the same title. And, to carry on the tradition, I introduced this title in the third volume too.

You’re very active in promoting your books, by participating to events we’re talking about above, as well as on social media (you post on your blog; Olguța even has a Facebook page). (And) Because of that you always find yourself on top of the Arthur sells. Do you think this kind of involvement goes without saying in order to be successful or is it a favour you’re doing to the publishing house?

You don’t have to do anything; nobody can make you do anything. I mean they can through a contract. There’s usually a clause that states the author will be involved in the actions of the publishing house and will do everything to the advancement of the global good and of the respective volume. But it depends very much from person to person. You do this thing vainly if you’re doing it badly or you’re not good at it or you don’t feel like doing it. I’m doing it because I like it. And I’m promoting my own books unashamedly on Facebook from time to time, not all the time; I suppose there are people that turn up their nose, but I like to do that and I think it’s working out for me. But if you’re doing it badly or you don’t feel like doing it, better drop it. Sure, the publishing house shouldn’t necessarily count on the PR and marketing activity of the author, because that’s not their job, but there are things that can be done and if time allows you to do… I have a very flexible schedule working from home as a translator. I can schedule my meetings with children and any other things. It depends on the context. But I wouldn’t count too much on the availability and the will of the writer. Because they’re still different things. Sure, if they’re actions organized by the publishing house at which the author can participate, its very okay. It’s trickyin general, because this is a pretty complicated domain; it’s not a breeze to promote a book or any other product without annoying people in the process.

Speaking of annoyance, this is the first question that popped in my head when I thought about making the interview: you received the “shame gain”, as you said on Facebook, for the Harry Potter translation that caused a typhoon of massive proportions?

We got a lot from there. I’d log in on Facebook every morning to see how many comments joined the already 400 existent ones from the first day where the old Harry Potter fans were cursing me because I dared to put a title that didn’t suited them. Very few people knew that it wasn’t me the one who put that title, but the publishing house, it was a choice made from the 2nd volume. I translated the 6th volume. The respective phrase, which I won’t name here, is present since the 2nd volume. And if they had read in details, that’s when the mass protests should’ve started. It’s a very odd thing with Harry Potter. It has very many and very vehement fans. There are the fans of the first translation, the one from Egmont that came out in the 2000s. I remember when the volumes came out, during that time I was working as a bookseller and I used to open the packages they were in.

And bad publicity, still publicity? Did it work?

I guess so. I mean, you can’t find the first translated version, only on OLX or online, and they’re pretty expensive. The Arthur version can be however found in bookstores and can be bought anytime. I’m not talking about me, because I’m not the coolest translator from there. We’re talking about Radu Paraschivescu and Florin Bican, the ones who translated the other volumes. They’re experienced people and they have a clearly defined sense of language. So one can say whatever they want, but we’re talking about some good years of work.

Do you still receive echoes from then?

Yes, last year I think I met with someone who had started laughing about the respective translation and the chosen title. In the end he told me. We departed in a kind of fight. A grudge for life, but it is what it is.

Staying in this translation zone, because you translated books for children as well as books for grownups, although I know you don’t like this differentiation, with which one of those you feel more comfortable? With what type of text? As a translator.

I think with the children’s books. I see this thing as an opportunity to enter the mind of other writers’ anyway, and that being what I do, writing books for children, every translation of this type is an opportunity. You know… when you’re translating a book you perceive it differently; you feel it differently than if you’d simply read it. When you have access to the original and you know exactly what they tried, if not really what the author meant so say. And I see that as a useful tool for the other side, the writing side. I think any translation can help me, whether I like it or not. Even if I’m using it only for the mistakes or things I don’t like, you learn what are the things that annoy you and the things you shouldn’t use. Sometimes it gives results and all of these things sum up somehow and form the finite product in the books I’m writing. I really try to learn and go a little farther every time.

And how did you learn to translate? Or can this profession be learned? I know there are a couple of schools, institutionally speaking, but how do you learn?

You learn by translating. School is very important, sure, but nothing compares to experience. I don’t know how things at the respective schools are; I have no idea what they’re teaching you. But I came across some things I didn’t know and it was pretty hard for me in the beginning. I started with philosophical books… Actually, I’m wrong: the first book I’ve translated is The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot. Which I translated frustratingly, because I wanted to buy it and I couldn’t find it anywhere, not in any antiquarian bookshop, there was no edition on the market, so I got angry and I said I wanted to translate it myself. I know that I bought then, because I needed it, the text of the poem. And I know I traded a princeps edition of Cioran for a volume with T.S. Eliot’s poetry. I can’t tell, not even retrospectively, if it was a good choice or not. And that’s how I started translating. That was the first thing, and it was obviously really hard in the beginning because this part with the internet wasn’t really developed and we’re talking about 2002-2003, around that time. And back then it was much more difficult to do research than it is now, when you can order books, you can read and search online and so on, the literary resources are literally unlimited. And that’s how I started… I translated that and I got a little bit calmer, but I translated a William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven an Hell, together with a friend, for Paralela 45. I collaborated with them for these two books. After that I started translating philosophy, I graduated Philosophy. I started collaborating with publishing houses that published books in this area. I got to literature and literature for children much more later. After some years, which coincided with a very, very interesting period, of collaborating with the IDEA magazine from Cluj, which is a magazine of contemporary art, the most solid and oldest magazine in this area. And I translated for them for 15 years, from a zone with very little information, and I learnt a ton of things. And I translated very much, thousands of pages probably, during those years…

You said one learns by practicing, but who gives you feedback regarding the quality of what you’re doing?

In the worst case, the public. In the best case, the copy-editor, who come to say and says “look, here you did that”. And at IDEA the editors are really, really good at this, all, from the editorial office to the proofreading, everything is really professional. And I had some meetings to work on the text where I was told why in a certain sentence is preferable the usage of a certain word than I’ve used and so on. Stuff like that extended on many hours and that are very annoying in that moment, but very useful. Regarding literature, children’s literature, actually, I entered with the Percy Jackson series of Rick Riordan. I talked to the people from Art, form Arthur, they sent me the book, I made the translation, which was obviously very flawed. And then a very cool thing happened: Florin Bican had moved to Cluj not long before, where I live too. Being a collaborator of the publishing house, I had a meeting with him, when he read my translation, he said he found it okay, that it can be worked on, that there’s potential in me as a translator and in the translation to be published and we met at one point in a room and stood in front of a computer to discuss the things than can be done better. I still hear his voice sometimes, when I have a query, and he tells me “look, here you’d better to that”. And he was right. And the coolest thing is that after this meeting we became friends and we remained friends to this day. We discover all sorts of mutual references and he’s a really great guy, with a lot of humor, and I like that about a person. This year we met too a couple of times, with a mask on and off the beaten track.

Speking of Florin Bican, do you have a short list of translators that you like or admire? From which you learnt something.

Yes, of course I do. Radu Paraschivescu is a very good translator. Iulia Gorzo… I like Florin Bican very much. Florin Bican can’t be equaled on the poetry side, the verse side and the rhyme side. He’s by far the best translator, and not only for children’s literature, although he has a clear preference for it and that bonds us together somehow. But the things he can do on this side are incredible and it’s really worth studied with a pen or marker in hand. I think he’s the best translator for children’s literature at the present moment. I always try to learn from the things I find out from him.

Everybody, everywhere writes that you can’t live out of writing alone, but anyway, this writing comes under various forms. Do you manage to live out of writing, translating and so on? If you want to answer that…

Well, it’s not private, it’s painful… I’ve already got over private. I could live a couple of hours a day… I could live 2 or 3 hours from writing, but not longer. If things worked like that. To the limit, it’s very hard. One cannot live from writing alone in Romania. Translations are, again, poorly paid, this is common knowledge, it’s not a secret, I didn’t come up with this piece of information. I do more things concomitantly. I translate, write, I’ve been holding some creative writing classes for children for a while now too. And, I don’t know, I write an article from time to time, and there’s always a project going on in which I involve myself, if I can. I shut down my laptop at 10 pm, that’s my working schedule. I begin in the morning, around 8:30, after I take little Alex to kindergarten and all day long I’m doing something. Because that’s the only way one can survive. I chose such odd and poorly paid domains to activate in… In a way it’s my fault too. No, it’s very hard and to the limit. A child asks me once in a while: I want to become a translator, I want to become a writer, what are the chances? And I tell them: “Kid, find something else, if you can, or do that as a hobby once in a while, and don’t count on this to buy a car, a house and raise two children too!” It’s true, you can get to other things from there. I tried to censor myself a bit after I told them to do that as a hobby, because there are already people with a steady income that want to translate books for children or adults as a hobby, without being paid. And they’re just spoiling the market.

We’re approaching the end and I wanted to ask you what the key ingredients of a cool Facebook status are. I know you asked that at a certain point and the first one who had responded was T.O. Bobe, who I found to be your Bucharest counterpart and you his Cluj counterpart, I haven’t decided yet, and I think it’s the perfect combo So, what is it? What mustn’t lack from a status?

It depends on what people you want to attract and what reactions you want to kindle in them… I try to introduce the humour there and cast away somehow the daily frustrations and angers through statuses, but no more of 2 or 3 every day. That’s what I’m trying to tell to people and to my friends. There are very few people in this world that have something so say in more than 3 statuses on a day. But I try to be somewhat funny, but there is another face of the coin, because now, every time I’m trying to say something serious, people think I’m ironic. I can’t post a single serious thing, because people think I’m kidding and they either don’t comment, either the respective post doesn’t even appear as seen.

And if it were to be made an animated series based on Olguța, what studio would you like to collaborate with?

What do you mean what studios? Buftea, we’re Romanians! Would there be another option? With a Romanian studio, of course. I don’t know, I don’t trust film adaptations too much, nor these transpositions in another settings, because the film adaptations of the majority of books I liked very much turned out to be horrendous or didn’t please me in any way. I can’t really see Olguța on screen or in another setting. I’d like to be argued against, but I think this character is very much based on voice, on that interior monologue that is pretty hard… I mean, what do you do? Do you use voice-over? Neh, it doesn’t work. I don’t believe in this. The tone and the irony that comes out of it matter very much. And this thing… if you take the irony out of Olguța and leave only the action part, the result will be the dullest book in the world. I used a ton of clichés there on purpose. It stays a soap opera… There are professionals that work with soap operas; I don’t want to be one of them. For a start, I’d like it to be published in other languages too. That’s what I’d like, I have to admit. The ego of the writer. I hope that will happen.

The last question: a book that you’ve liked very much and you think was underrated and you’d throw now in the #BookTok whirlpool, for the TikTok teenagers to cry on it and make all sorts of viral videos, what would that be?

I don’t know what to say about this thing with teenagers, I didn’t really get into that zone, because teenagers are the most curious creatures in the world and it’s very hard to write for them. My expertise stops at the 7th grade. A book I like very much and which I read like five times in the last two years is the book of Louis Sachar, the guy who wrote Holes, which is entitled Sideways Stories from Wayside School; it’s a book of 6th grade level that I like. I’m totally in love with it. And there’s another guy, an American, he’s name is Richard Peck, who wrote two books for children, teenagers, pre-teenagers published at the Arthur publishing house. A Long Way from Chicago and another one, A Year Down Yonder, which I found absolutely sensational and didn’t receive almost any praise. Well, that if there were people that would take care of the children’s books, write a chronicle and talk about… thing that’s not happening at this moment. This is an absolutely sensational author that I’d like to see more read. I made him a chronicle for his last volume in the Familiamagazine, which I started collaborating with this year and where I have a column of literature for children, books for children and, well, I try to promote there the books I like very much.

So there’s someone taking care of promotion.

Yes, now it wasn’t the case for me to brag, because I talked too much about me for my taste. But yes, I hope there will be as many as possible, to be as many qualified people as possible to take care of this, not because they have to, but because they like to read literature for children.

(This interview was video recorded and transcribed. Translated into English by Silvia Codescu.)