Adelina Butnaru illustrates books even when her feet are cold, although it is better to do it when your feet are warm. When she calls her cat, she says: Jucăușanski, Alintăceanu, Zaharin, Motănașă, Spielzeug. Even though the name in his ID is different. The last time I saw her she was sailing in a book with both fresh water and salt water.

I will start abruptly. Did you find out whether the rug tickles when you vacuum it?

Slippers slipper, socks sock, cat beans cat, the feet tickle the rug and the rug tickles the feet. Cat beans also make biscuits, when they don’t bean around. I’ve had a kitten since June, and, therefore, the most biscuit-worthy rug.

Are you one of those people who have been drawing their whole lives, or is there a “t0” of this passion which turned into a profession?

For me, what is visual is easier to understand. It’s easier for me to do math using my fingers, especially in summer, when I can also see my toes. I’ve always been the type of person who lives inside their shell and I think that this passion is more of a way for me to express myself. When your mind is full and you don’t want to talk, it’s better to draw something. I took drawing classes in primary school, I attended art school and art/design university. I’m curious, that is why I chose design. It seems like you can always invent something. When I go to the store I say one cupcake please, here are 5 fingers, thank you.

When did you switch from doodling on the last pages of your school notebooks, with ink and neon markers, to drawing in a pocket notebook? Was it a sort of professionalization?

I have a trotting horse in my head. Or a rooster which goes „cock-a-doodle-doo”. Someone is doing the laundry in my head. This is what it feels like. Using a washing machine. I don’t know what other people hear, but I need to write things down in a notebook in order to quiet everything down. I don’t talk much, and the words you say without sound don’t count. I like this noise, when I was little I used to think that it was my superpower, that I was the only one who had this inner voice, or that there was someone inside who told me what to say. Ever since I’ve learned how to write, I’ve kept a sort of diary. I would doodle, write down my thoughts, stories with my classmates, quotes from books and word definitions. When I was in kindergarten, I used to draw women with antennae, I don’t know why. I had a notebook filled with ladies with antennae, all dressed differently. I even used to sew clothes for my dolls. Once, I cut off a piece from a curtain at home, another time I burnt a blouse with the iron. It was a blue blouse with a big black mark left on the chest area. It could have been a stylized penguin, but the adults didn’t understand. There has always been a sketchbook in my life. I believe that I was a professional even back when I cut the curtain, and drew characters with antennae. I don’t feel like there has been a switch from my childhood notebooks to my official sketchbooks from high school and college. Perhaps the contents, the techniques, the paper quality, the instruments are different.

When did you join the Faber Studio team?

After my Master’s. I liked that they always had a dog around and that they had very diverse projects.

And what is the studio dynamic like? Can you choose the projects assigned to the team, are they directly assigned to you or can you find other projects and bring them under the studio umbrella?

When you arrive at the studio, Dog #1 jumps on you. Then Dog #2 jumps on you. Dog #2 is a golden retriever and he forgets that he’s no longer small and wants to fit into your arms. Dog #1 is a dachshund and he sleeps in a pretzel shape, but only after licking your face. Each person chooses their projects and each person can find new projects. It’s like a Swedish buffet. Today we eat logos, tomorrow we eat layouts, the day after tomorrow we eat illustrations, or calligraphy, and so on.

You drew on stained glass windows, mugs, covers and book pages, sometimes even book spines, magazine covers, shirts, posters, postcards. Maybe even a few walls, but I hope it is not too much of a stretch. Does your style differ from one to the other? Is the pleasure you gain from doing all of this different?

A childhood friend recently told me that I had imaginary friends back in the day, too. The pleasure of creating characters and worlds was there. Other demands arise when it comes to the technical part, but besides that, it’s still a story told visually, only the medium is different. I had a friend I would carry in my pocket and talk to, he was called Gogonica. It was a piece of plastic, it looked like a yellow chip. That’s what children do, they speak nonsense and they humanize objects. I believe that is also what illustration does, first of all.

And how did you come to do all of this? How did you come to illustrate, Advice for little girls by Mark Twain and the fables from Arthur Publishing House?

Trei Publishing House (Virginia Lupulescu) was looking for an illustrator for Mark Twain’s text. They knew that I did graphic design, but they didn’t know that I drew illustrations. I have always enjoyed Twain’s humour. The text has force and courage, it’s different. So different that I found the book on the psychology shelf... The publishing house was pleased with the illustrations, it was just that, by the time I finished the illustrations, the editorial plan had changed. Nobody got upset, they were building the PanDa collection back then, and this title did not fit in with the others. So it appeared at Tzim Tzum Books.

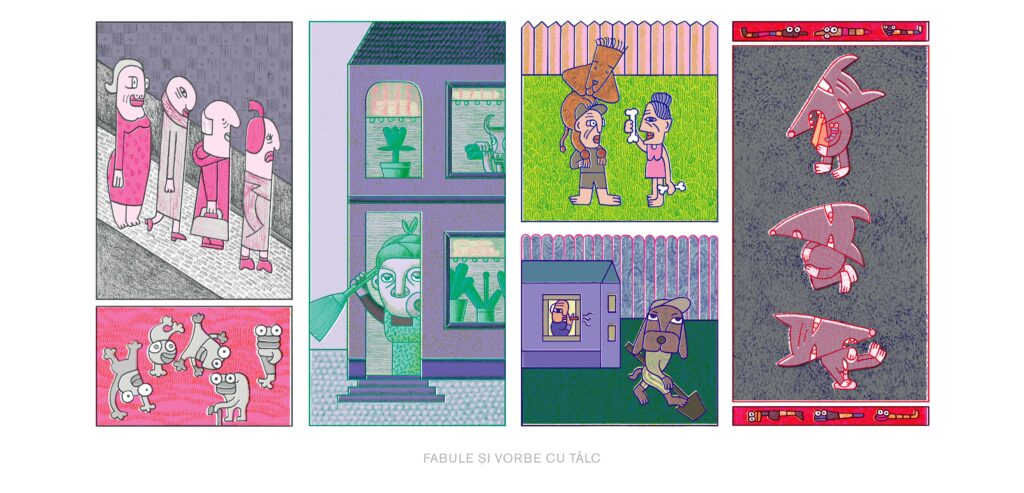

Diana Zografi suggested that I should illustrate Fabule/Fables. Her point of reference was also the Twain book. We had great communication, she even got me acquainted with Suzi the bunny. Diana Zografi and Adrian Săvoiu curated the texts and they were cool.

Where does your involvement in such a book cease? When you turn in the illustrations? I saw that (no, I am not a stalker stalker, let’s call it research) for Fables you also went to the printing press. Are there still things to modify at that point?

I’m in a small room. I open the door and I enter into another small room. From that small room I go towards another door. I open the door in order to open another door. I walk in and out of rooms and windows until I find the illustration. There has never been a fixed deadline for the illustrated books and that was what allowed me to move around, to experiment, to throw things away. I did not have a period of time during which I only worked on Fables. But jumping from one project to another can be advantageous. That way, you never get stuck, and while you’re working on Project A, you come up with ideas for Project B. And your mind is always envious of what the other has, even though the other is also you. When the deadline for B is approaching, you say, maaan, how I’d love to work on A right now.

Your involvement as an illustrator never ceases. When the book has reached the bookshop shelves, you’ll make advertising posters, you’ll give interviews, you’ll talk on the radio, you’ll go to the book launch. It will pleasantly haunt you even two years from now. The publishing house was very involved, it offered us everything we wished for, even the book launch with Ada Milea at Cărturești Modul.

When you send the document off to the printing press, it means that your work and your interventions on that digital document are done. The next step is theirs to make. They process the document, they make the imposition, the printing plates, they calibrate the colour intensity, they fold the pages, they glue them together, they do the cutting, they add the finish, they bind the pages together.

I went to the printing press on the occasion of Twain’s book, too. It was printed at Fabrik. My first permission to print was Zigzag Journal by Geta Brătescu.

In 2017, Advice for little girls won the grand prize in the contest The Most Beautiful Books from Romania. Did that influence your career or your following collaborations?

Yes. That was when the phone started ringing for artwork which included drawings.

For other books, such as the psychology and the psychotherapy books from Trei, you designed the cover and the illustrations. Which one came first? The design or the illustrations? And how was the collaboration with the production director, with the publishing house in general?

The layout comes first, always. Even more so when we’re talking about a book collection. The dimension of the book, the mirror page, the type of letter (dimension, interline, weight), the colours, how many colours, the hierarchy of the text, the alignment, the composition, the space for the illustrations, the space for the text, the positioning of all the elements – these are all established.

For the Contemporary Psychoanalysis collection I also did the graphic design, and the small illustrations. For the Psychology-Psychotherapy collection, Faber thought everything out, and my colleagues and I took turns at creating the mandalas.

The production directors let us wade in special colours. When it comes to the technical specifications, every book is a negotiation between the editor (the person who invests in the book), the production director and the graphic designer. They must keep in mind the message the text/the image sends (the type of text, the illustration technique), they pay attention to the writer/illustrator.

If you know how to ask for things, you receive them. And I’m not talking about dreaming about impossible things; you saw an effect somewhere and you want that same effect. I’m talking about visual culture and about understanding when that effect matches the given context. The editors and the translators care about the content very much, and they can suggest a certain kind of alignment, or a certain cover, or a direction which modifies the concept. They carefully look at the text and they have access to some details not even the writer has taken into account.

What is the difference between the usual colours, those you find everywhere, and the special colours, the Pantone ones? How are they different?

The usual colours are CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black). The special colours are special because they have a different intensity/specificity. For instance, silver or neon colours cannot be obtained from CYMK. PANTONE is not, in fact, the company which produces those colours, it’s only the company which organizes them into a system and then makes them into colour samples.

And what colour are you?

In my works, I use all the colours. I choose my colour palette in accordance with the given subject.

For clothes, I like black, blue, turquoise. It also depends on the quantity. I have very simple clothes, without patterns or prints. I have many colourful socks. All my jeans are the same model, only the colours are different. All my shoes are black. My wardrobe is not too different from Dexter’s wardrobe. Considering that my mind is always buzzing, I feel the need to be as basic as possible on the outside. But don’t be scared, clothes can be spectacular when they’re simple by using the right cut for your proportions.

You said at one point that the hardest part of your job is sitting on a chair. Followed by knowing when to stop. What is the easiest part?

The easiest part is finding like-minded people. For instance, I say look, I’ll give you the following words: poliptoton, poliptota, gutapercă, and what I get in exchange is: heautontimorumenos, maniabil, knickerbockers.

Do you have any favourite tool? The nib, the ink, the pencils, the graphic tablet or what do I know, any other witcheries artists use in order to take people’s minds off of things and take them into their world?

I am in love with pencils, nibs, liners, fountain pens, parallel pens, brushes, erasers, colour tubes. I could spend an entire day in a stationery store and touch the writing tools and the notebooks. I mostly draw using a 0.7 LAMY CP 1 Black mechanical pencil on Moleskine notebooks. I also have a ukulele, a harmonica and stainless steel Ikea salt shakers which I use in order to make music. So I play. Advice for musicians: the best way to play an instrument is on your cat’s belly.

The truth is that there was some sort of witchery in the preface to Fables and wise words, and in the texts from the Creative Writing classes organized by Revista de Povestiri. The commentator from “Stai să dau save” (Let me click save) is right, I would also give a thumbs up to every line and every phrase. They really hit the right spot. What is the deal with writing and how do you make it work alongside drawing?

In a way, it’s still a type of language, whether it uses images or letters. I believe that drawing actually helps me when I write. Without being aware of it, I apply the visual rules to the written texts. Until now, I haven’t written with a certain purpose. Most of my texts aren’t about anything in particular. I create a database of small events. I write at least one sentence in a notebook, daily. Here are two examples.

17.04.21 I went to the subway to buy bread. They didn’t have any. I went to the pharmacy, I’d like two bread loaves, please. We don’t have any. Not even unsliced? Fine, then I’ll just buy Nurofen.

07.02.21 My shoes have not been outside in a while. Today we walked about 2 kilometres together. And they gave me blisters. They said: “Dude, aren’t we brand new? Let’s give her some blisters”.

Where did you learn how to write and how to tell stories which stay with people long after they have finished reading them?

Writing feels like drawing to me. I have an image in my head and I put it down on paper, either by drawing it, or by writing it. It’s like a game. Or like a way to tidy up my mind.

I’m not a writer. I sometimes forget commas, other times I mix the word order in a sentence, because that’s how words come to me.

I believe that drawing pushes you to see things from different angles. And that’s what I do with stories. I take a character and I go around it until I see what it looks like from behind, what it looks like if I look at it from the top of a building, if I switch its hands for its legs, and the other way around, if I take it from the couch and put it on a bicycle, or if instead of a ribcage, I give it a dulcimer.

When I was 10 years old, I wrote my first poem, about a sparrow. In the 12th grade, I had a very good Romanian teacher, Laura Stănică. I showed her what I wrote. She showed me what she wrote. She had a poem about a pimple on an ass cheek and it seemed incredible to me, that you could write about a pimple on an ass cheek and make it sound so lively, so funny, so appealing. When I think about a teacher who has made a difference in my life, she pops up into my head. She was very much human, besides being a teacher.

I participated in various writing contests organized in Romania, I won a few of them. We used to come at the Bucharest Metropolitan Library, together with a few peers from the Tulcea literary circle and with professor Gheorghe Bucur. I liked it because we went to McDonald’s, in Tulcea we didn’t have McToast and McFlurry. I used to write poems with many neologisms back then. I was wondering why I was writing, and where that would take me, because I didn’t necessarily see the point. But I liked skipping the usual classes and this was something pretty tangible. We were excused from school when we went to events which included texts. Neologisms were a defence mechanism, I didn’t want everybody to know what I was thinking, or what I didn’t have enough of, or what I had too much of. Even now, writing seems to me like going out on the street while wearing only underwear. Even when you write about somebody else. In the meantime, I got more interested in short stories which uses the simplest words. Something like: God allows us to slit chickens’ throats.

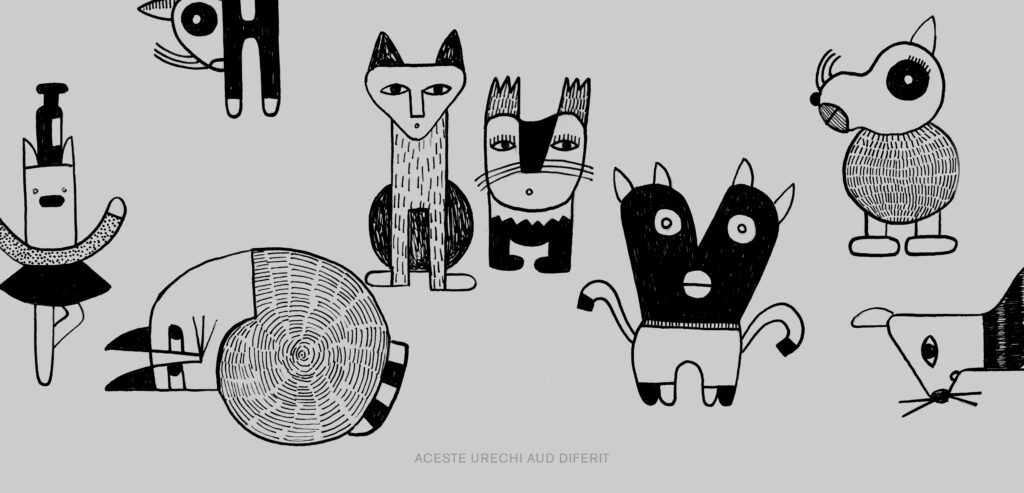

What characters have you come up with recently? And what books?

A book from which cats come out.

Something you want to say at the end of the interview.

If you don’t have anything to do today, think about what life without slippers would be like, take a breath, appreciate the doors that don’t creak. And, in the end, I want to defend my big-nosed characters, you should know that big noses screw in more easily. [Translated into English by Irina Adelina Găinușă.]

The title, the intro and the photos belong to Adelina.