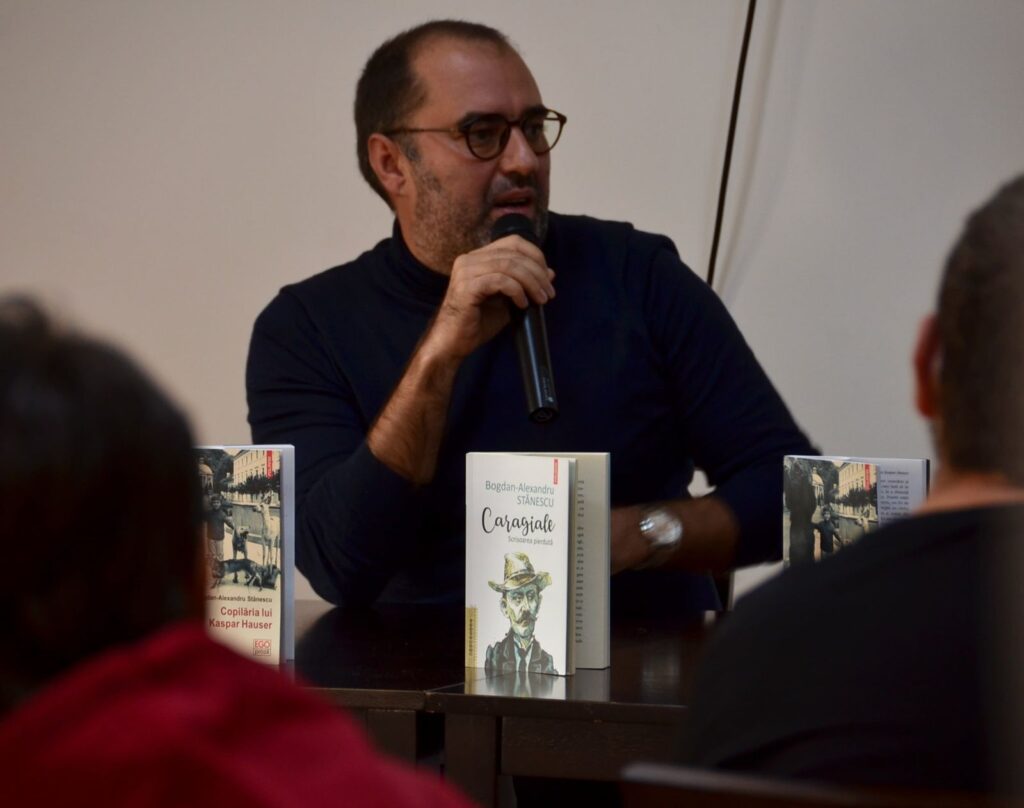

Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu is a writer, translator and editor. Since 2020 he has been the coordinator of Anansi. World Fiction, Trei’s imprint dedicated to literary fiction. Until then he was Editorial Director for Polirom for fifteen years, taking care of their world literature collection, Biblioteca Polirom. He published essays, poetry (among which Apoi, după bătălie, ne-am tras sufletul and Adorabilii etrusci), novels (Copilăria lui Kaspar Hauser, Abraxas Abraxas and biographical novel Caragiale. Scrisoarea pierdută). Besides, he wrote book reviews and is now writing essays for Observator Cultural and Dilema. He has a PhD from the Faculty of Letters of the University of Bucharest, where he also taught and will soon be teaching again as part of the master’s programme in Publishing. The Romanian book market, synchronised with and continuously in touch with the world’s literatures, owes its debt of gratitude to a great extent to Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu’s unceasing dedication, passion and professionalism.

‘I enjoy slow reading and am always happy when I have the time to fall into a dreamy state prompted by reading for half an hour’, you said some time ago. How did the latest half-hour of daydreaming feel and what brought it to life?

Two weeks after Bookfestwas over, I retreated to the village of Vadu, trying to finish writing the novel I had been working on for two years. It was really a retreat during which I wanted to rest my thoughts, since the novel tried to depict a whole epoch and contained many characters and biographies, thus it required a few rereadings and sinking back into the story. I took with me Cormac McCarthy’s dyptique The Passenger and Stella Maris, marvelously translated by Iulia Gorzo, and I admit that the fragments about physics in The Passenger, or the depictions of hallucinatory landscapes in that dementia of a country called the USA helped me profit from my half-hours during which I had the time to daydream. For me, daydreaming is the piston that drives imagination, an active kind of rest similar to the dream, if I may say so.

Editura Trei turns 30 this year. During the last four years, Anansi, the god of tales, was at the heart of the publishing house, although he already seems to have been there for much longer. What does Anansi mean in terms of published titles, number of copies sold, bestsellers and longsellers?

Anansi. World FictionBeyond figures and statistics, Anansi. World Fiction is a wonder because we could keep within the limits that we set for ourselves from the start. For me, that is more important than the Pragmatic Editorial Sector. Of course publishers cannot exist without sales, therefore good sales – as good as they can be for a literature collection – played a role too. The total number of titles exceeded 100 just before Bookfest. In terms of bestsellers, I would like to first and foremost mention the Nobel Prize winners Annie Ernaux and Jon Fosse, but also a few surprises, which belong to both categories: Jaume Cabre’s Confiteor, Franz Kafka’s Diary and his Letters to Milena. We were also surprised by Alwarda, Ruxandra Novac’s poetry book, which reached the 4th print run since it was launched (print runs were 1,000 copies each). The average print run is 2,000 copies, and most titles had a second one. Least but not least, Anansi also means thorough planning, that is why we are currently working on 80 titles.

In some interviews you talked about the restlessness and ceaseless work during the years at Polirom. Did the rhythm change once you started working for Trei? Where does your involvement start and where does it cease when it comes to Anansi titles?

The quality and intensity of my work did not change. There were a few changes in my routine due to Trei’s internal work processes. Searching for titles, reading them, making proposals towards the editorial board, their acquisition by the rights team, finding the ideal translator of each individual title, then on to proofreading (I proofread ‘in my free time’), creating cover texts, final readings before printing – I do all these things either alone, or together with my colleague and Editor-in-Chief Alin Croitoru, with whom I have been working for almost 15 years, the two copy editor colleagues Mădălina Marinache and Ruxandra Câmpeanu, and last but not least with painter Andrei Gamarț, who creates the covers of all our titles. If you want to be successful on the Romanian book market and not only work to secure an income, there is no rest: the cornerstones of the book market are new releases – and this is a double-edged sword. The most anxiogenic effect thereof is that you are never done working, that there is no otiosemoment, when you can just lean back and enjoy the books you published. During Bookfest 2022, Anansi. World Fiction presented 17 new releases – some might think we completely relaxed the week after the book fair was over. No chance! Besides, it is always frustrating to realise that readers do not ponder over books too long: and I’m not talking about sales, I simply mean they don’t take some time to ‘digest’ what they have been reading. It all seems like a bottomless pit in which thousands of tons of words are thrown (it is worse if, like me, you perceive words as having weight), and this is truly tragic for someone who is also a writer.

This spring, Anansi. World Fiction became an imprint, but before it was one of Pandora M’s collections. What did this change mean within the Trei Editorial Group?

Anansi. World Fiction basically surfaced from under the tutelage of Pandora M publishing house and became a largely independent legal entity. The change mostly affected finances and accounting. It also immediately resulted in a clearer configuration of the publishing profile of Pandora M, which now wholly comprises books for children and teenagers: picture books, middle grade and young adult, if I were to use the specialised terms. What used to be a series at Anansi became a collection, which means the person who configures the imprint is under more pressure – the different collections must be balanced in terms of quantity.

There are, in Anansi’s portofolio, recipients of some of the most important international literary awards, from Nobel to Goncourt and The Booker Prize, and you had published many of these titles before the winners of the awards were announced. Do you have a sixth sense that allows you to detect future success? What is the impact of such international recognition on the public’s reactions and on sales?

No, there is no such thing as a Whirpool sixth sense. As they say in pedagogy and psychology, you need to practice for at least 10,000 hours in order to be able to master a field. In 2025 there will have been 20 years since I started working as Editorial Director, and these were long years, during which my preoccupation was not that the working hours were over, nor were weekends or holidays. If you are possessed by literary fiction, if you breathe and live through it, it is impossible not to perceive some very fine accords and just know when an author is truly great, while another is ‘fake’. Besides, if you seek to build, not to make a hit, at some point the construction will raise above sea level. It would all pay off, but the reward is fed by the mire of many failures. At the root of each award there are others that, to my mind, would have deserved more. As to the impact of awards on sales, it is already well-known that sales are dramatically influenced by the Nobel Prize. I would also go as far as saying that it is the only award that will bring a major change in the commercial perception of the product, if I were to use Newspeak terms. There were also pleasant surprises when it came to The International Booker Prize, but I cannot really analyze the situation, since Gheorghi Gospodinov was already a ‘good-seller’ by then. Timing also played a role, since the award came just on the night before Bookfest, and the book was already published – it was one of those moments of editorial black magic.

Although you already said that you don’t necessarily follow the most recent international launches and don’t take part in overrated book biddings, I imagine that you cannot wholly avoid stressful rights acquisitions. Which where the biggest battles for Anansi titles?

The answer to this question is related to what I said before: we fought hard for Itamar Vieira Junior, the Brazilian writer who was a finalist of the International Booker Prize this year; this is just an example that comes to mind right now. But the true battle for literary and ‘very’ literary fiction is fought by the publishing house internally. The temptation to spread yourself too thin, to exaggerate by acquiring rights ceaselessly is always there, because the ‘literary’ sirens don’t stop singing.

When Anansi was launched, you stated that your aim is not to have commercial success, but to narrow the selection range from ‘literary’ to ‘very literary’. Taking this into account, what are the financial resources that support the imprint? Has the god of storytelling already gathered enough followers so that is it sustainable?

I think you already found the answer. There is, indeed, a follower base, which we created by using marketing very humanely. We wished that at least the Facebook page of the imprint had a very human face; right from the beginning, in 2020, we decided that Headsome Communication would take care of promotion together with the PR department of the publishing house, and they were of the opinion that we needed to go beyond the commonplace and stiff strategy of sharing book covers and quotes. Besides, the public knows when you are for real, and when you claim you publish literary fiction but actually offer something completely different. But to be more exact, yes, there are quite a lot of titles that sold and sell well. I can count absolute failures on the fingers of one hand, and these are actually the ones that give the measure of a publishing house or collection.

What are you preparing for the autumn-winter season?

As I’m writing this, these are just about to finish warming up and enter the field: Istanbul Istanbulby Burhan Sonmez, The Son of Manby Jean Baptiste Del Amo Dostoevsky in Loveby Alex Christofi, A Swim in a Pond in the Rainby George Saunders, Love in the Days of Rebellionby Ahmet Altan, Slouching Towards Bethlehemby Joan Didion. Until Gaudeamus Book Fair, 12 other titles will be preparing just outside the field, but I want it to remain a surprise.

This year, you will come back to teaching as part of the Master’s programme in Publishing. Especially because I am jealous and would have also wanted to have the chance of taking part, I cannot but ask: how will you structure the course ‘The Book – From Idea to Promotion’?

I think the course will be very practical, offering a ‘holistic’ approach to the industry, so that the students are aware not only of the product called ‘book’, but also of its historical background. I will try to combine outlining a history of the concepts of book and publishing house with a clear definition of all the components of a publishing house, from proofreading to marketing, promotion and sales. A Publishing student must not only know how to proofread, but also what copyright is. They must know which is the average sum a bookstore takes from sales revenues, not only how to create footnotes. They need to know what ISBN and CIP are (particularly what these mysterious letters stand for), how a cover is created, how a promotion campaign is structured, what commission means, what an external or a translation contract looks like. What the difference between reediting and reprinting is. All this information ensures the mental hygiene of those who set themselves to work in the book industry.

Your novels are represented abroad by Susijn Agency in London. How did they become part of the agency’s portfolio and what is the dynamics of your work relationship with founder Laura Susijn?

I don’t want to pretend that I was chosen by the agency from a vast list of Romanian authors. I don’t think that, before 2017, it ever crossed her mind to represent Romanian authors at all. Because I want to dispel any dilemmas, a literary agent receives a commission of 20% from each sale. If you sell a title in 5 territories, with an average sum of 1000 euros per sale, and your agency is located in London, then I let you calculate and tell me after how many months bankruptcy happens. In 2010, I took part in a fellowship in Guadalajara together with Laura Susijn, and I had the pleasant surprise of being able to talk to her about Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Baudelaire – something completely unusual in today’s publishers’ world. I had bought the rights for a work by Dubravka Ugrešić from her and I could then witness how fiercely she fights for her authors. In 2017, I asked her without having any expectations if she would be willing to help me, without a formal agreement. I was younger then and somehow blinded by my modest national success, so I thought… I don’t know what I thought then, but I surely don’t believe it anymore. Fortunately, she accepted. I still feel guilty about taking so much of her time, instead of letting her work for the authors who really bring her money.

Both Copilăria lui Kaspar Hauserand Abraxas were already or are about to be translated, among others in Croatian, Polish, Hungarian, Bulgarian and French, and your most recent novel will be published by Gallimard. At some point you said that being published by this prestigious publishing house means that a book is validated on a national and international level. How were interactions with the translators of your books so far, as well as with the foreign editors, and to what extent did these editions influence the trajectory and sales of the original publications?

Did I say that? As I was saying before, although I am immensely grateful to all those involved in selling my books to foreign publishers and to my wonderful translators, I am already past the age where I can maintain the illusion of an international career, although objectively – as objectively as I can manage – I don’t think Abraxas Abraxas is that far behind the good books I read and edit. I didn’t have such close interactions with foreign editors, as the procedures are very well-defined. The exception is my editor in Bulgaria, Manol Peykov, an absolutely fabulous person with whom I am in touch constantly to exchange ideas, especially about publishing. Nevertheless, I truly became friends with my translators, because most of them had questions and were curious about certain aspects of the books they were translating. I became friends with Lora Nenkovska, my translator into Bulgarian, and with Nicolas Cavailles, my translator into French, if I were to only give two eloquent examples: a very sensitive relationship is formed, one which is mediated by a text that came from within yourself. It is as if you talked to your child’s educator, who teaches him or her a foreign language.

Which moments brought you most joy professionally so far?

There were numerous happy moments, but the most recent was, of course, when Anansi was created. And its success. I still have difficulties escaping the joy of holding in my hands a book I worked on for several months. If you can still feel that joy, I think you have already accomplished a mission very few know when they get into publishing: you need to be honest in your love relationship to the book, and you must not lie, particularly not to yourself. Apart from that, there are the joys brought by important acquisitions: Hemingway, Nabokov, Camus. The joy of publishing books by László Krasznahorkaiand Péter Nádas, the joy of receiving a letter from Don DeLillo… Nerdjoys, indeed. But I am the way I am and there’s no sense in trying to lie to myself.

[The photos are part of Bogdan-Alexandru Stănescu’s archive.] [Translated into English by Luciana Crăciun.]