Irinel Antoniu was a copy editor at Institutul European Publishing House and at Univers Publishing House. He translated from French books by Gabriel Osmonde (Andrei Makïne), Alfred Jarry, Gaston Bachelard, Antoine Compagnon, Romain Gary and many others. He is a rebel and passionate reader, he collects old French books and has rare subtle irony.

What’s your most recent perfect combo as far as books, music and guilty pleasure?

I began Cornul inorogului, my friend Bogdan Crețu’s novel, at the same time with a Bessarabian wine named Unicorn. I recommend both of them, successively and simultaneously. For the musical part, as someone who has listened to Norocul inoroguluiover 2000 times, I allow myself La licorne by Les Compagnons de la Chanson (from which, to my knowledge, Antoine Compagnon wasn’t part of).

What does the work day or night of a translator look like?

Mes nuits sont plus rebelles que vos jours. I become active during the night, without verging however on diligence. That’s when I translate, copy edit, read, make coffees, swear, listen to music… In the morning I go to sleep discontented (contented translators need to quit their job), and after sleep there are some imprudent people that tolerate me around them.

What’s the first book you’ve translated and how did you get to translate it?

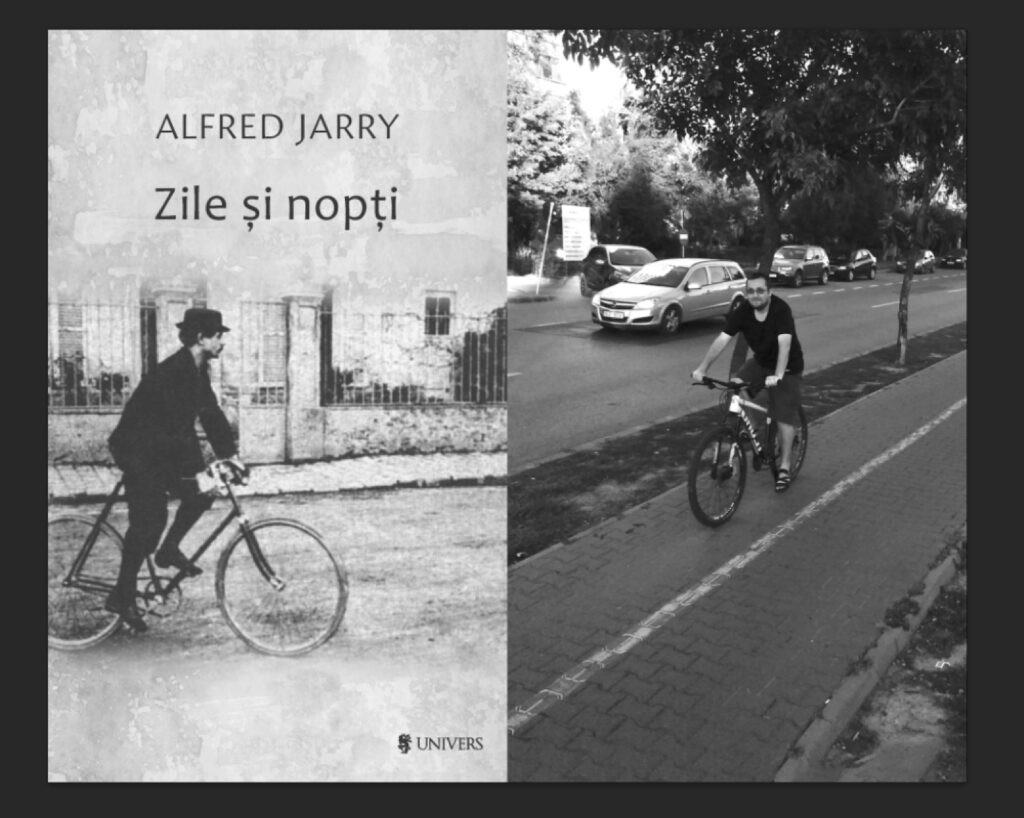

Because the Institutul European Publishing House from Iași had lost half of the document turned in by the translator (on floppy disk, to place the unfortunate occurrence in the exact point of Antiquity), it fell on me, a fresh copy editor there, to redo a part of the book right away. I wanted to translate so I couldn’t say no. That’s how I ended up co-translator of a volume about military matters in which the wooden language interlaced with the iron language, it was called Europe’s Defence. I got my revenge years later translating Alfred Jarry’s antimilitarist novel, Days and Nights.

What’s the process when you start a new translation: does the publishing house suggest you a title or is it possible for you to suggest a book for which the publishing house to buy the copyright for?

The proposal usually comes from the publishing house. It happened however the other way around too, for me to suggest titles that the publishing house should buy and give me to translate them. The ideal situation was, obviously, to translate on my own, for my selfish pleasure, some books, and a publishing house to be so keen on loss that they would publish it. So far I’ve managed to sneak three books with this method.

You’ve collaborated with multiple Romanian publishing houses. What expectations do you have from a publishing house?

I’ve collaborated with six publishing houses. Only with two of them I had problems regarding the on-time payment. It’s a good balance, other colleagues were less fortunate. Then I want my translation to go through a normal editorial process, to be copy edited, proofread, have a not too embarrassing cover, and to be published preferably during my lifetime. I don’t want it to be slaughtered just to make the book more sellable (if that’s what the editor had wanted, he should’ve picked another book). And, without being vain, I think that the name of the translator is a necessary piece of information in the books’ presentations. I’ve seen on the sites of the publishing houses that even the weight of the book is specified, but not who translated it. And we’re talking about the person who’s “guilty” for the version who gets to the readers.

What about the expectations of a publishing house from a translator?

Not to cut corners. To work considerately, to be obvious that they’re interested in the text. To ask themselves from time to time: ”Is it possible that this author wrote a two pages anacoluthon or did I did something wrong?”. A poorly done translation that needs a lot of work within the publishing house (and the copy editors and the proofreaders of tranquillizers) is worse than a delay. Furthermore, to run from the sin of originality and the desire of correcting the author. The author has the holly right of writing badly, the translator is not allowed to usurp them.

Do you have bad memories with texts or fragments that wouldn’t let themselves to be translated?

Oh, of course! Precisely from authors that I liked very much and that I’ve cursed awfully at that moment. I would’ve punctured Jarry’s bicycle tires gladly, for example. Or Romain Gary, with a play of words at every three lines. Or Camille Lemonnier, with terms which I didn’t know if they were French archaisms, rare Belgian structures or he simply had made them up. On the other hand, there are those texts that are not necessarily difficult, but boring, bad to the point of nauseating, through which you go like through jelly. Luckily, it hasn’t happened to me too often, the last time was with a novel from what’s called feel-good literature. I hope I will be able one day to conform to the advice of my first boss, professor Sorin Pîrvu, of not being a reader too when I translate.

You’ve translated fiction and nonfiction. To which types of text are you the closest and on which do you work with the most pleasure?

With an exception, the nonfiction books were requests from the publishing houses, I didn’t choose them. I’ve been translating only fiction for many years and of course I like it better. But I started as a translator of scientific books and, given the fact that that time coincides with my youth, of course I’m nostalgic thinking about it.

What are the working tools of a translator?

The Romanian grammar, many, various and carefully picked readings before thinking of starting to translate, an ongoing learning of the source language (using any means, from linguistic treaties to TV crime dramas), modesty and solitude. For everything else, there are dictionaries.

Before going to printing, a translation lands in the hands of a copy editor and, with a little bit of luck (and financial resources), of a proofreader. Have you ever had disputes with an editor regarding a term or a nuance? Who’s the first to give in?

Not disputes, but I had discussions. At Univers Publishing House, where most of my translations were published, I had the luck of having as an editor Diana Crupenschi, an experienced translator herself, who has helped me many times to improve the text, not only by eyeing the inanities that had slipped me (that’s the easy part), but joggling nuances together until we found the best one.

You’ve copy edited yourself. Do you recall from that position a more heated discussion?

The heated discussions took place with the good translators. With those that turned in catastrophic versions there was no point in discussing (you don’t want to see how not even in emails they don’t put a comma after vocative). I’m nostalgic when I remember my amicable fights with Lavinia Similaru, the excellent translator of Bolaño,Maríasor Asturias.

Do you continue to follow the transit of the book after you turn in the translation to the publishing house? Are you interest in how is welcomed?

I’d like it to reach bookstores and to be read. I don’t know if translation reviews are something that’s still done in our country, but sure, I’d be interested.

Do you re-read the books you’re translating after they’re published?

I flip through them, but I’ve never re-read one integrally. Of course, if we’re talking about republishing a book, I’d go through them thoroughly.

What’s the translated book that you’re most proud of?

Days and Nights by Alfred Jarry. I’ve loved Jarry since I discovered him in my teenage years. Before me he was translated by the likes of Romulus Vulpescu or Luca Pițu. And, as a testament of eminently pataphysical reception, this small antimilitarist novel gained a review in Observatorul militar. I dare any writer who has earned nothing but reviews in Observator Cultural.

And what book or what author would you like to translate?

Jean Genet, Pompes funèbres. Maybe I’ll even start translating it on my own. (If there’s a publishing house willing to publish this novel suited for all the cat lovers…).

Do you have a model among translators, which you admire and from which you learn or have learnt something?

There are many translators out there that I admire. I’ve even read books that didn't particularly interest me, just for the pleasure of going through a translation. Some of them are so good that they intimidate you. For example, Laszlo Alexandru, if he hadn't translated and written nothing but The Life Before Us and Zazie in the Metro, he would’ve still had an impressive work, there are two translating masterpieces that you can easily put next to the greatest Romanian novels. Șerban Foarță translates in Romanian the most impossible texts. Octavian Soviany translated integrally Baudelaire's poetry. Of course, our goddess of French translations remains Irina Mavrodin. Speaking of I.M., I’m waiting eagerly Cristian Fulaș's new translation of In Search of Lost Time. And The Laws of Hospitality by Klossowski, promised by Dan Alexe.

What’s the deal with this profession? Do you learn or do you steal it?

You can't really steal anything, because you don't sit next to a translator when he’s working. Practical translation courses have always been taught at foreign language faculties and now there are even master's degrees in translation studies. But I strongly believe that we learn mainly by reading.

The fatalistic question of the interview: what do you think is the future of translators in the accelerated rise of artificial intelligence and automatic translation mechanisms?

Like the past. No worries, artificial intelligence can’t replace the troubled intelligence of the human translator. Eventually, the softwares will translate each other. The only thing that could change that would be the villainy greed of a publisher.

What does a translator have and a robot doesn’t? Besides Busuioaca de Bohotin and Dennis Wilson's Pacific Ocean Blue.

Doubts. They’re very important. The problem is not that robots would take our job, food from the table and cigarettes from our mouths, but that we could robotize ourselves. Very confident translators are a terror of mine as a copy editor. (Otherwise, Dennis Wilson drowned, drunk, in the blue of the Pacific, and Busuioaca is a nauseatingly sweet wine that is bearable only in the company of some memories.)

And if we’re still finding ourselves on the fatalistic side of things: there is the axiom that goes around through the fair according to which in Romania one cannot live only from writing (but this writing also has its forms). Is it possible from translating?

I think Pavel Coruț lived from writing. I've heard that some children's book writers manage well. I tried with translations when I was young, and it was really adventurous. I don't know anybody to live just from that.

You are a passionate reader, especially of French literature, but you are also a lover of old and precious books. When and how did you start collecting them?

Francophone literature. I'm not necessarily a collector, I gather books to read them. And especially to re-read them. But I can tell you the exact moment when I became aware of my bibliophilia: when I discovered an accomplice in the person of my good friend, the literary critic Antonio Patraș, with whom I started talking out of the blue about our last preys in antique bookstores. That happened while we were playing football-tennis. He is much more erudite than me and more of a refined bibliophile, so that’s why he’s the first I go to brag to about what I’ve found at Tîrgul Cărții and so on. Bespectacled people passions.

What characteristics must a book possess in order to catch your bibliophile attention?

To be in French ("j'suis snob, foutrement snob", as the song says) and to be cheap. The latter condition will, of course, vanish when the translators' fees rise dramatically. And to be a book I really want to read, I’ve never bought one just as an object. Of course, I’m glad when I find a rare and old edition of such a book.

What are the most important pieces of your collection?

My nephew keeps asking me, sometimes as a joke, sometimes more seriously, as my heir, which books he can sell to gain at least enough to pay for my cremation when my time to push up the daisies comes. I don't know if they would be important to anyone but me. They’re not even very old; the oldest is a edition of Destouches' plays from 1811. Some belonged to various personalities, from Elena Văcărescu or Pamfil Șeicaru to Radu Beligan. I have an edition from Maldoror from Mihai Beniuc's library, which proves that our comrade read the most decadent literature. I’m moved by the old signatures, such as that of an "Alice", handwritten, in the 1920s, on the cover of many good books which ended up in my hands. I still manage to laugh by flipping through books by Wolinski, Cabu and Charb. L’Histoire de France vue par San-Antonio is not a rarity, but it was given to me by my former professor Luca Pițu. And Antonio Patraș brought me from Paris a novel called Le bibliophile, about the perils of our vice. Finally, I have an edition of Le roi lépreux by Pierre Benoit on which the previous owner bluntly wrote: "Stolen from R. Antoniu".

If you were to recommend to a collector of rare books from around 2246 a volume translated by you what would that be?

I translated a few years ago a book of short stories by a French author settled in Brazil, Stéphane Chao. It's called The Ideogram of the Night. I’ve asked the publishing house recently for it to give it to somebody and apparently it’s no longer in the deposit. So it already meets the criterion of rarity. (Translated into English by Silvia Codescu)