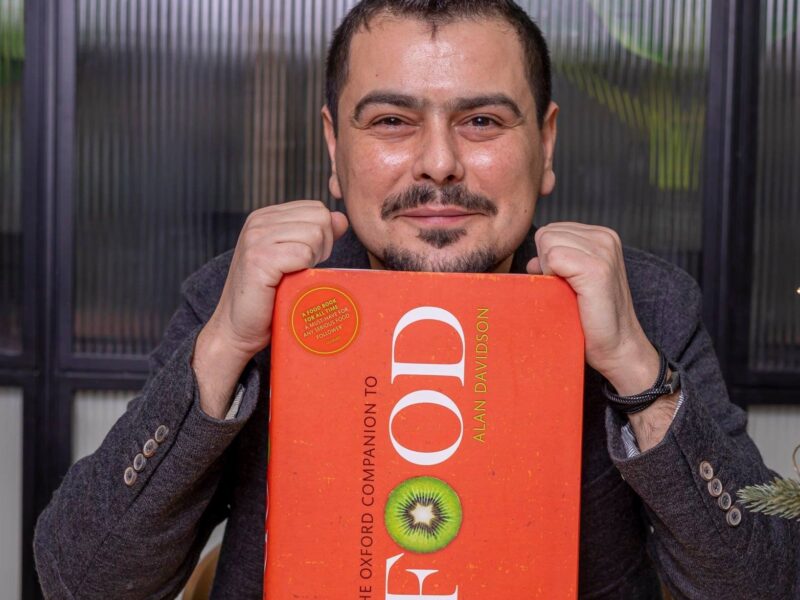

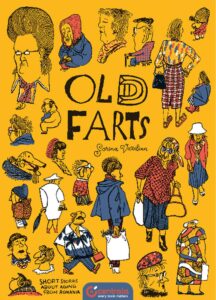

Sorina Vazelina Sorina Vazelina is an illustrator, graphic designer and comics author. She creates books, comics, prints, murals, collages, illustrations which are both merry and gloomy. She published Old Fartsin the UK, a graphic novel which received a prize in The Most Beautiful Books from Romania competition. Her artistic variedness brought her, among other things, collaborations with magazines (Scena9, Decât o Revistă, Vice etc.), NGOs, festivals, musicians and publishing houses.

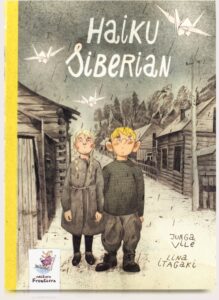

I thought we should start from Siberian Haiku and your experience with this book, since this is where my opportunity to interview you came from. How did you join the team from Frontiera Publishing House? I read somewhere that you had previously met the two Lithuanian authors many years ago and that your and Jurga Vile’s stories somehow overlapped even before that.

I had indeed met them at the book festival in Göteborg two years prior, in 2019 I think. They were launching Siberian Haiku and I was there with Old Farts, the comic book. But the people at Frontiera weren’t aware of us having met before. They bought the copyright and Lina Itagaki and Andreea Mihaiu from FOI Magazine recommended me for the job. It was funny that somehow our paths combined. That’s how we got to know each other and started working together. They gave me a few pages at first. I started out by making a collage out of the characters which I found, but it was a very laborious process. I compared different texts in Lithuanian, Italian, English (Alina Nucă translated the book into Romanian using the French edition). My role was to write out the text bubbles, the letters and a part of the text using the graphic tablet. Besides my writing, the book also has a font Lina had created and which Liviu Stoica introduced. He was the one that took care of the DTP part of the project.

So that means you also worked hand in hand with the illustrator.

Yes. Lina is very meticulous about her work and she wanted to monitor the entire process. She went through various correction stages and insisted on writing the titles of each chapter herself. And there is also a part where some words in Romanian are knitted – I think she took care of that part in each edition of the book.

While reading the book, I was wondering how you tackled the graphic side of things. On paper? On the computer?

You start off by writing down your ideas, just as writers do, but graphic design also has this formal side to it that has to do with the fonts and the layout. And it gets more complicated when there’s a lot of text involved. All this marriage between text and graphics gives the book a greater depth too. I think this text is trying to break some of the limits that communication has nowadays. How many people still write letters to one another in this day?

Being published by Frontiera makes it a children’s book, but I don’t think it’s limited to a certain age group. Did you feel you were working on a book created for children?

Having read the book, I realised that you never know if all the letters sent to the father or the uncle actually reach their recipients. And that’s interesting. To me, it seems that this is where the magic of such books as Alice in Wonderland or Siberian Haiku lies – they are valuable regardless of age; the older you get, the more you can decode and unpack various layers or look with another eye upon it. It’s the kind of book that you can read at different points in your life and I find it to be an all-round required read in the educational context of today’s Romania. It helps the kids get into the characters’ boots and relive history way easier than blockbusters do. Thanks to Lina’s naïve style, you can empathise very quickly with the graphic novel or visual narrative. There’s nothing that will rock your world, as in Batman, or, I don’t know, something monumental; precisely thanks to the naivety and innocence you are able to take in some of the drama and cruelty of the events. It’s just as in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. I listened to an interview to understand how he had come to write this novel. And he said that he kept wanting to write about his experience in Dresden, during the bombings. He was having a drink with a friend, unwrapping memories. At one point, his wife comes and breaks in, saying “you were just kids” – “You were just babies then”. Similarly, Jurga and Lina use magic, as well as some whimsical elements, and these details are like gentle strokes through that chaotic Siberia.

How long did this project take you? How much time did you spend working on it and how did you “knit” it, alluding to the letters mentioned above?

I think they contacted me around the end of December or beginning of January and they told me that it must be ready by the 14th of February, so I was running it close. Lina sent me the files and suggested to test it out, see how it goes, since I had never worked on such a project before. But I enjoyed it, because it resembles what I do with the comics. Although it was more work than expected, I finished it on time, before the end of February. The printing process started in March.

Liviu Stoica’s name is also present alongside yours, he being the one who took care of the DTP process. Could you explain to those people like me, who are less familiar with the differences between the two professions, what the activity of each of you entails, maybe relating your answer to Siberian Haiku?

He’s the one doing the layout, the pagination of the text. He’s not concerned with handwriting or creating fonts. He only checks if the text fulfils certain indications/prerequisites and if the colours are ok.

So he practically pieced together the parts that both of you worked on.

Yes, Liviu Stoica was the only one that had access to the text written in Lina’s font. He took the pieces I worked on, put them together with his own parts, and forwarded them to Lina.

So that means that 3 people worked on the visual side of this book.

Yes. It’s a demanding project both in length and involvement. We all got involved and we wanted it to turn out well.

Siberian Haiku isn’t the first project revolving around deportation in which you got involved. I recall the comics about the deportations from Banat to Bărăgan, published in Scena9. Is there a common ground between these projects? Once I read something about an uncle of yours which had been deported to Siberia.

We actually had a laugh about it, me, Lina and Jurga, when we got to know each other. Well, not actually laughing, eh... Dark humour, what else can you do when you talk about Siberia?! They told me their story and then I realised that I also have an uncle who was deported, my parents told me about it. It’s a longer story. My grandmother recalls a part of it, my father, who spoke with my uncle, another part… And so I want to somehow solve the puzzle of the stories, put together the different pieces.

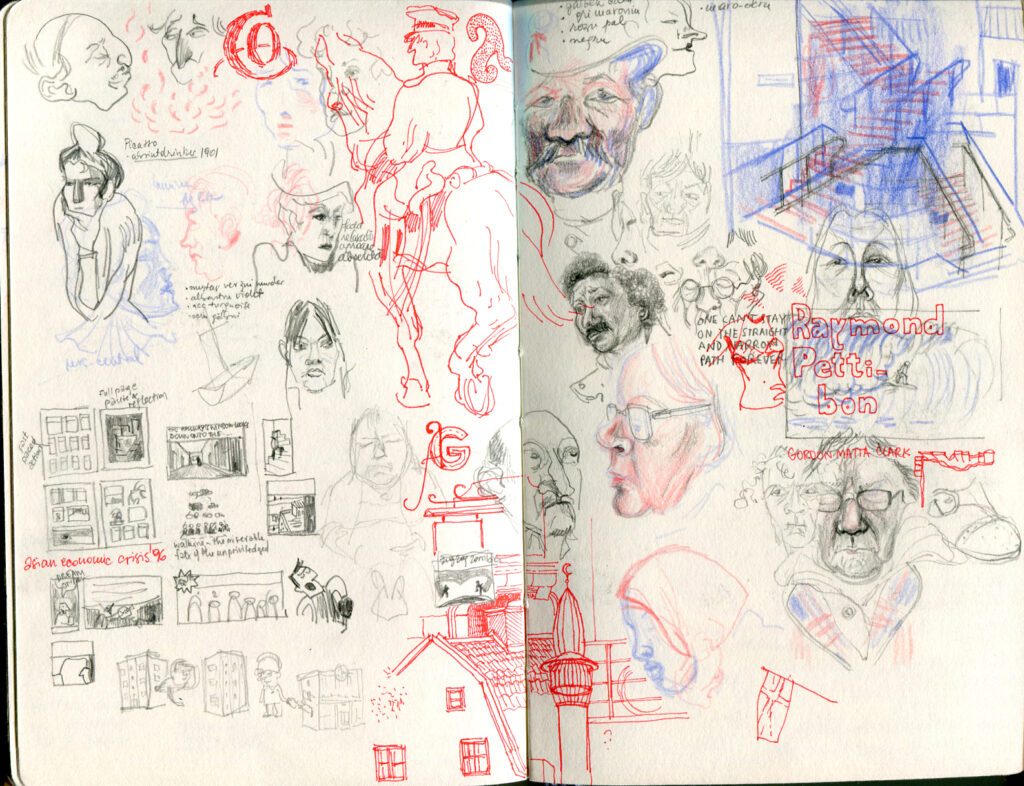

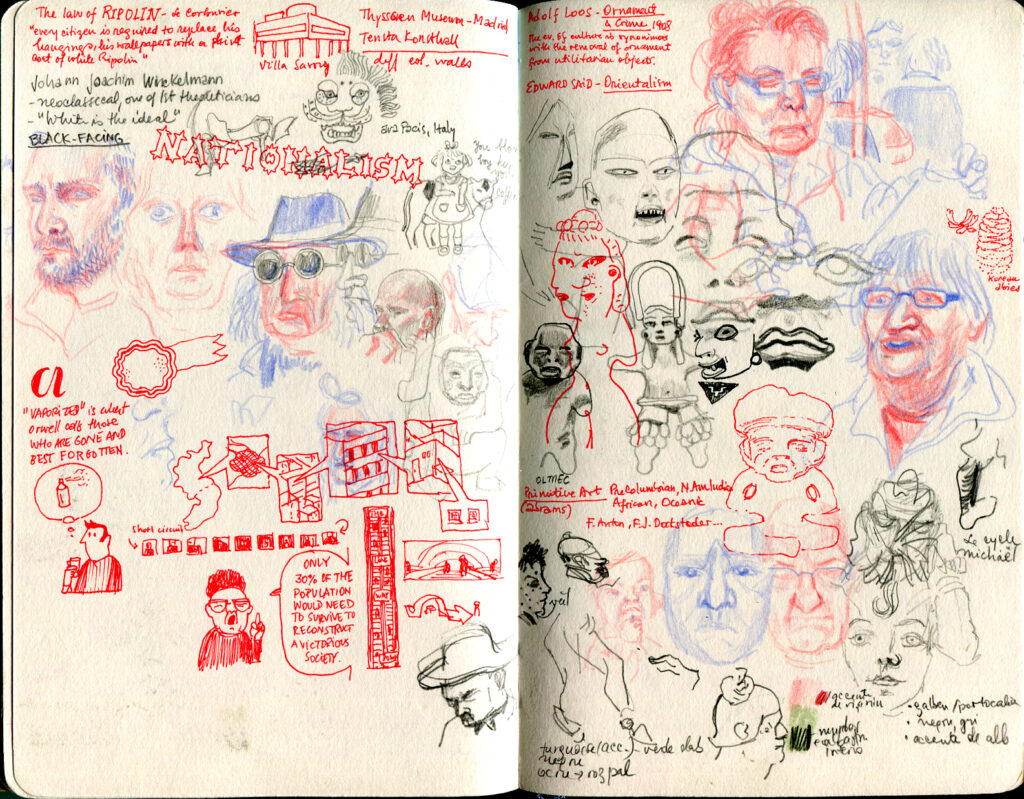

Do you have a documentation process that you go through before you start working on the comics? Where do you gather your ideas from?

The library and the albums are of great help. Some ideas come to me along the way, others I catch hold of from different projects and sometimes they come to me naturally. But, due to this, it takes me a lot of time to finish something. If I get the documentation part done, it goes by a lot faster, since it’s the most laborious. Then, when the text’s ready, I have to figure out what illustration style fits the narrative best. Sometimes it’s the visual that comes first, other times it’s the text, it depends on the story.

Since we touched upon your personal projects, how was your relationship with those from the Centrala Publishing House, where you published Old Farts, or how does it continue to be? Also, what is the post-publication life of the book like?

Well, it’s quite weird. There was a contest which I won in 2015. They published it in 2017, using money received from the Romanian Cultural Institute in London. All the money made from sales go to Centrala. They gave me a sum in the beginning, which I mostly spent to buy books and distribute them here, in Romania, through my APP (Authorised Physical Person). They also wanted to translate it into Polish. But I don’t remember what the negotiations are or what happened with it.

It didn’t work? I know that Centrala has divisions in England, The Czech Republic and Poland.

Yes, but they’re not that spread out, so to say. Michał and his wife, Anca, take care of the publishing house. For many years, they attended various comics festivals and that’s where they earned this name for themselves. These connections in the underground scene or between alternative publishers are very cherished. During these festivals, friends are made and people discover many wild things. They were able to grow on this path. They moved from Poland to London, at one point they lived for a time in Prague and they attended FRAME comics festival.

I happened upon their contest on the internet and I said to myself “Alright, I’ll send this story”, which, in fact, was a cluster made up of many ideas; I had been waiting to get them out for a while and I needed a boot up the backside to make me do it. What captured a lot of my interest was the distribution part, because it’s mostly grasping at straws. Here, in Romania, I thank my lucky stars for Vlad Niculescu from Cărturești & friends, because he sells it there. They always had my back, he and Aurel Minculescu, and the entire team at Anthony Frost. They gave heart to us people from the comics scene, because they had a part dedicated to manga and comics. When I entered that room, all seemed calm and joyous at the same time: the philosophy books stood next to the comics, they also had sheet music and books about directors and screen writers. It was as though you were entering a giant and colourful bird house, in which all sang and coexisted in a symbiosis.

You mentioned Göteborg before. How did you get to attend the fair?

The RCI (Romanian Cultural Institute) proposes a list of people from various areas. They probably have a scope of interest or some themes, and so they draw people that they are in contact with in these projects. When I went to Offprint London [book fair dedicated to the editorial houses specialised in contemporary art, photography and graphic design] in2019, for the launch of Old Farts, Michał asked the RCI to help me with the accommodation. He helped me with the ticket.

The themes you tackle in your comics seem very heavy subjects to me. Can they make for a competitive advantage in the comics world?

I wouldn’t like what I do if not for the heavy subjects. It’s not a competitive advantage, but I like it. I don’t like doing things that are too easy. At the same time, I couldn’t tell you what the target audience is. I sometimes start from issues which I encountered while working on various journalism projects or I find some stuff during random research and they get interconnected. I rely on this chemistry that forms in time: more elements come together and, at some point, a spark forms between them and a story is born.

But I need leisure time in order to be able to create comics. I once asked the Surducan sisters (because they’re quite prolific and they keep coming out with graphic novels) how they split up their time, since they also work on editorial illustrations and other projects. Maria told me that they had some periods in which they would work during the summer. That’s how they wrote Vacanța lui Nor [Nor’s Holiday], during a whole summer. But they also spent time on the story before that, on framework. My process is more chaotic. I wish I’d make it neater, since I have some baby ideas there that are waiting to blend with some older ideas.

Do you think there is, or there could ever be, an East-European comics market that could compete against the Western or Japanese one?

We just didn’t team up. We are fools for not working together. The Serbs are quite cool, they have the Novo Doba Festival, with comics and all that kind of stuff. They brought a lot of cool artists, such as the people at Le Dernier Cri from Marseille. They also had a workshop with Anamaria Pravicencu and Octav Avramescu from Jumătatea Plină in Bucharest a while back. Novo Doba is like a motor that keeps pulsing. I also saw multiple initiatives coming from Hungary, various independent festivals. I think the Bulgarians are doing something about it too, but it’s no “great wave”, like that of the Polish people back yonder with their posters or the animation school in Zagreb. We aren’t yet enough people to make up that great of a team. But it might work if we follow the formula that Jurga and Lina have, this visual dance.

In your presentation that’s up on Scena9 , you mention being half graphic designer, one quarter illustrator and one quarter comics author. What does each of these professions entail and why did you separate them this way?

All these occupations of mine fluctuate.

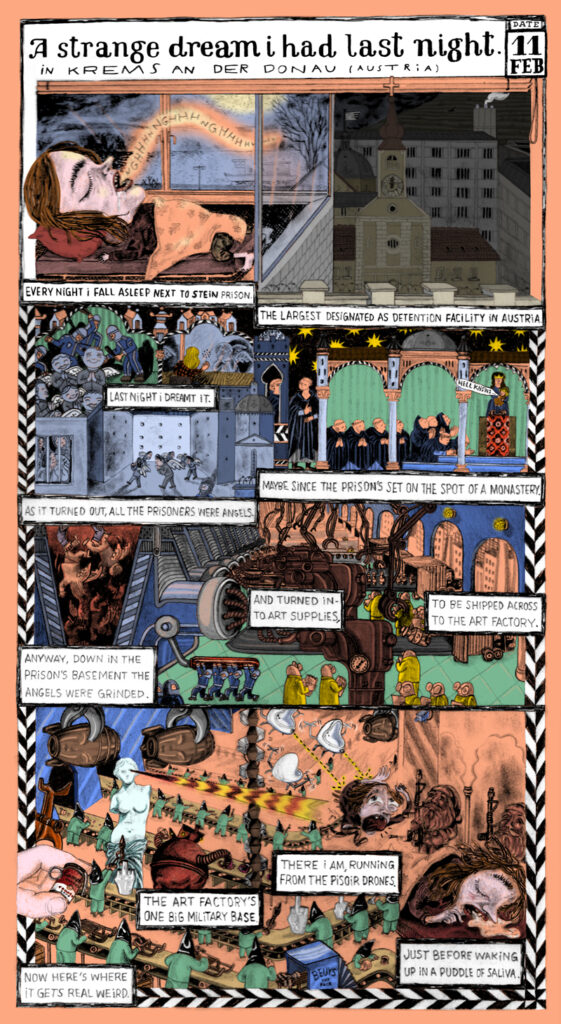

Graphic design: you give me a Word Document and, based on the amount of text in it, I can make it into an album, a book, a leaflet, program, poster, visual brand identity, packaging. As an illustrator, I mostly worked on editorial articles. Or, as an example, how I worked alongside Vlad Odobescu for Vice: he came up with the text and I did scroll comics. The entire article became both a visual and a literary experience. When I create comics, I also come up with the text if I’m up for it. It’s some sort of graphic design masked by a fine curtain.

As far as graphic design is concerned, you work for and with the needs of the client; same goes for the editorial illustrations: it all depends on who’s publishing your illustration. More often than not, the team gives you directions to follow, sometimes you come up with something and discuss it with them afterwards. But I always felt that comics had this somewhat personal dimension to them. It’s a rhythm that you create out of text and images and there aren’t that many barriers, precisely because it’s not a very profoundly present domain here, in Romania, and that gives you the space to explore. Anyway, I ended up doing all of these things because I needed to make the best out of what I got. But it’s beneficial because you need to somehow have both visuals and text interwoven if you want to successfully convey information nowadays.

To what lengths does your freedom stretch and how do you negotiate your freedom of expression when you receive a strict brief from a client?

I wasn’t always granted this freedom. When I started out, there were many men in the industry. Afterwards, it all changed, more and more women started joining in and I’m happy about that. At the beginning, I had two bosses and I learned some things from each of them. I also learned what I we want to do. When I was working on the companies’ projects, I was always preoccupied by the client’s needs and respecting some quality standards, we were a team after all. After that, as a freelancer, you have to be your own boss.

When you start off, people won’t let you do what you want, but you learn to figure out more or less what they want and you start to negotiate. Sometimes it’s precisely this barrier that helps you find solutions and figure out what the best path to take is. Other times you have to give them literally what they want, because they’ll never realise that what they asked for makes no sense. During the time I spent in studios, I saw to it that I also worked for myself, besides my responsibilities there. And that’s how people got to know me and we started collaborating. For example, Andra Matzal helped me out a lot. I knew her from Think Outside The Box, from Veioza Arte and from Tataia. There were also other people, like Sabina Baciu who worked at One World Film Festival. And that’s how people find out about you, by speaking out. That’s why, in every project that you work on, you must try to both do what you like and also contribute with something. I watched Captain Planet as a kid, what would you expect… But I had a lucky star, a very lucky star.

Did you have collaborations with other editorial houses, besides Frontiera?

I worked on the book put together by Minitremu with Dan Perjovschi’s drawings, Colouring and Activity Book. They came to me because they had published the Romanian version with funds given by the AFCN (Administration of the National Cultural Fund), but they wanted the English version to be sold internationally and they thought that the design wasn’t good enough. I redesigned the book, a project funded by the AFCN as well. I also handled the Hungarian translation, another AFCN project in collaboration with Minitremu. I also worked on Florin Bican’s Reciclopedia de povești . Matei Branea did the illustrations, I did the design, and the book received a design prize at the Ready to Print Gala (Gala Bun de Tipar). I also worked with Youth’s Theatre (Teatrul Tineretului) in Piatra Neamț at the time when Geanina [Cărbunariu] entered their team; I worked on it all, from the visual identity of the brand to their publication, a booklet of around 100 pages containing all the troupes that she invited. At one point I worked on something with Vellant Publishing House, but it was only a book cover. I also worked on that Czech-Romanian series, Czech-Romanian Relationships in Comics, of which Anamaria Pravicencu and Octav Avramescu published multiple volumes with help from the Embassy of the Czech Republic. I was responsible for the cover, for making sure that the InDesign was done well and all the pages were ok, so it was only on a technical level. I also collaborated with Hardcomics on their layout. With Aoleu. I worked on 100 To Watch, a bigger volume containing 100 Romanian artists which had been published by the ICR (Romanian Cultural Institute) when Patapievici was still working there. At that time I also worked on 100 To Watch, a bigger volume containing 100 Romanian artists which had been published by the ICR (Romanian Cultural Institute) when Patapievici was still working there. At that time I also worked on The Book of George, which was translated in Romanian and published by the Jumătatea Plină Publishing House. I was also a collaborator for the project Romanian Harm Reduction Network , as well as for the DaDeCe Association. They are now planning to release a heritage guide and a set of some sort of games related to heritage with the Patrimonia Publishing House, which is part of the National Institute of Heritage.

Going back to where we started from, to Siberian Haiku. Do you have any favourite characters or any favourite scenes?

The aunt who had a passion for Japan, because she’s the one through which the authoresses introduce the haiku in the narrative and keep it there up until you get to the concentration camp. And there was also Gentle Rosa, the one that foresees what’s going to happen and knows when the mother will get her voice back.

Didn’t you like Aligs’ sister?

The sister’s nice too, but I like that aunt of theirs. The concentration camp is always poignant with the issue that sexual assault poses and I feel as though she’s the only character which the book hint at having been sexually abused by those two guys, the comrades that were setting the rules there. But I don’t like having favourite characters, I think that each one brings something unique to the table…

You liked Captain Planet. This is a character, isn’t it?

Yes, yes… And that gander… The National Museum of Contemporary Art organised a workshop evolving around the book. A girl decided to draw that exact gander. They could draw whatever they wanted, but she took a liking to that character and so she drew it in Lina’s style. I sent it to her too. Simplifying the features of a character helps you keep them in mind easier. I find it quite cool that the character left its mark on the little girl and that the kids saw through the literary reference as well. It’s like an educational game. A book like this one puts forth many more lessons to learn, not only in history and literature.

[Transcribed and translated into English by Lucia Brînaru-Mitrofan.]

The photos are part of Sorina Vazelina's archive.